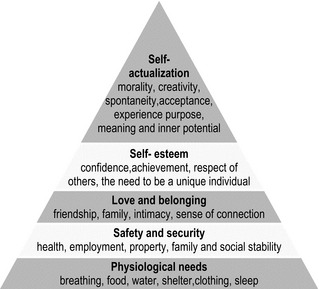

5 After reading this chapter, students will be able to: • Demonstrate an understanding of the wider veterinary business context. • Define the key functions of management and evaluate the appropriateness of different management styles in different situations and contexts. • Identify key motivation theories and understand their relationship to HRM. • Appreciate the relevant RCVS Day One Competence expectations for graduate veterinarians in the workplace in relation to ethics, professionalism and business acumen. • Identify and critically appraise the ethical and professional expectations of a veterinary graduate working in practice. The veterinary profession has undergone dramatic changes over the past forty years. There is now a greater focus on animal welfare; large-animal work has declined while small or companion animal practice has increased (Lowe, 2009). There has also been a gender shift amongst veterinarians in practice, and different business models now operate within the veterinary business landscape (Henry and Treanor, 2012; RCVS, 2010). Traditionally, the profession was comprised of small, privately owned, partnership practices. In the UK, these are increasingly being taken over or replaced by corporate chains or groups of larger practices (Henry et al., 2011). This trend, coupled with the introduction of practices owned or managed by non-veterinarians, has created concerns that the ‘managerialization’ of the profession could result in practice ‘unbecoming of the profession’, should profit maximization concerns overtake healthcare decisions based on the patient’s (animal’s) best interests. There are additional concerns that sales and marketing strategies employed within some practices may diminish professional status by reducing veterinarians to sales staff, striving to achieve monthly targets. In a challenging economic climate and an increasingly competitive veterinary business landscape, financial sustainability is difficult. As employers, practice owners are seeking graduates with business acumen – one of the ‘Day One Competence’ requirements of the RCVS. However, it has been claimed that UK veterinary graduates are insufficiently prepared for working in practice, unaware of the business environment and, despite the fact that most will probably work within or lead a small veterinary business at some stage in their careers, ill prepared for management or leadership roles (Lowe, 2009). As a new employee, management responsibilities are unlikely; however, after a relatively short period of time, many veterinary graduates may find themselves adopting informal management roles as they become more experienced veterinary assistants, especially within smaller practices. These roles could range from the smaller-scale management of the veterinary team in animal care cases, through to the management of independent revenue streams from particular service offerings or areas of veterinary work within the overall practice. Unfortunately, many veterinarians in the workplace may not appreciate the benefits of undertaking management training, even when they become business owners and have responsibility for employees. The RCVS (2010) survey data highlight that time spent on practice management and administration is reported to have steadily increased between 2001 and 2010, with this trend forecast to continue. Additionally, a negative experience in a graduate’s first post can dramatically shape their veterinary career, often triggering an early exit from the profession (Heath, 2007; RCVS, 2007). These studies have also highlighted the limited adoption of human resource (HR) practices, such as appraisals, that could make a positive contribution to the training, development and support of new graduates (RCVS, 2007, 2010). Business ethics is a branch of applied ethics that ‘addresses the moral features of commercial activity’ (Marcoux, 2008). ‘In particular, it involves examining appropriate constraints on the pursuit of self-interest, or (for firms) profits, when the actions of individuals or firms affect others’ (MacDonald, 2012). Recently, business ethics has explored financial accounting standards and practices, e.g. the Enron scandal or unscrupulous investment banking. Other concerns have also been raised, such as environmental issues due to corporations abusing the world’s physical resources and causing environmental and ecological damage (Esso); abuse of human rights, e.g. Shell in Nigeria; and animal welfare, e.g. KFC and McDonalds (McDonalds v Steel & Morris, 1997; Rose, 2007). Unethical HRM practice has also been highlighted, e.g. the use of child labour by the fashion industry or employers reneging on pension agreements. Business ethics in professional subjects, especially healthcare, are particularly problematic. One defining trait of a professional subject is the possession and application of the subject’s unique body of knowledge; this distinguishes it from other business ethics as clients are unable to understand fully the role of the professional practitioner. Clients must invest a high level of trust in the professional to deliver fair, honest and appropriate information to them, not limiting their choices or freedom and acting altruistically for the best interests of the individuals involved. When the choices to be made relate to healthcare they are more significant and intense, especially if the decisions involve life-shortening or serious compromises on welfare. A broader view of business morality is required in considering the role of corporate responsibility in society, as evidenced by the RCVS’s new Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS, 2012a). The professional identity of veterinarians is so important that if one is to be employed by an organization then the RCVS recommends that the organization not only allows veterinarians to adhere to their professional conduct, but also makes sure that they are appointed to director status, ensuring that the professional conduct of the business aligns with RCVS expectations (RCVS, 2012b, Section 17.5). Management, like veterinary medicine, is considered to be part art and part science; while some individuals will have natural aptitudes, there are skills, knowledge and behaviours that can be taught and learned by all. Henri Fayol (1949) considered management to be a primarily intellectual activity that, regardless of the type of business, involved four core functions: planning, leading, organizing and controlling. At a macro level within a practice, the owner(s) will undertake these tasks to manage the business in its wider business environment. At the micro level, veterinarians will perform these tasks when managing care in each individual animal patient case. People have a natural tendency to act and make decisions in a particular way; this is their natural management style. However, the management style adopted by a manager will impact upon the motivation and productivity of employees. Sometimes, when managing particular individuals or circumstances, managers may have to adopt a style with which they are less comfortable in order to achieve the best results. The main management styles are outlined in Box 5.1. HRM can be considered as a ‘business function that is concerned with managing relations between groups of people in their capacities as employees, employers and managers’ (Rose, 2007). HRM involves attracting, selecting and retaining (through appraisal, training and development, remuneration and team building) the right people for each post. It also involves ensuring compliance with employment legislation, dealing with whistle-blowing incidents and, where applicable, liaising and negotiating with unions. Today, HR is considered to have four objectives: (1) aligning HR and business strategy (strategic partner); (2) re-engineering organization processes (administration expert); (3) listening and responding to employees (employee champion); and (4) managing transformation and change (change agent) (Ulrich, 1996). While it may seem like a mixture of common sense and professional and legislative demands, HR practice today is informed by a long history of research into human motivation and organizational behaviour, in addition to attitudinal changes in society over time. Frederick Taylor (1911) sought to improve labour efficiency in a manufacturing plant; his work began what became known as the ‘school of scientific management’. This approach advocated an autocratic management style (whereby managers make decisions and simply give orders to those below them). This style was later (1960) identified by McGregor as a theory X1 style, i.e. managers regarded workers as lazy, requiring close supervision and motivated by pay. In scientific management, work was broken down into small chunks with people trained to perform a particular task. Jobs were repetitive in nature and ‘time and motion’ studies established normative work rates. Henry Ford used these concepts when establishing the first production line. Research into work motivation and the field of organizational behaviour gained momentum. In psychology, motivation is an explanatory concept used to describe why individuals behave in certain ways. Motivation itself is intrinsic to an individual and cannot be bestowed upon employees by managers; motivation is, however, affected by extrinsic rewards (tangible benefits such as pay, pensions, fringe benefits), intrinsic rewards (psychological rewards from doing the work itself, being part of an organization, profession or team, a sense of challenge or achievement) and social rewards (obtained by being with other people, sharing a sense of purpose, confirmation of identity and image of self) (Rollinson et al., 2002). This neo-human relations school of management focused on the psychological needs of employees and was heavily influenced by Abraham Maslow (1943, 1954) and Frederick Herzberg et al. (1959). Maslow identified five levels of needs that people seek to satisfy. These needs are organized into a hierarchy to reflect that, as one type of need is largely satisfied, the next higher level of need begins to act as a motivator (Figure 5.1). As physical and safety needs are met in a modern workplace, an employee may want to establish social networks to achieve a sense of belonging. If employees feel that their work is appreciated and valued by their employer, perhaps through promotion, pay and praise, they may be more motivated by an intrinsic drive for self-actualization, i.e. personal growth and fulfilment. Movement through the hierarchy is not one directional; people can move up and down the hierarchy as changes occur in their home or working lives. Figure 5.1 • Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Based on data from Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper. David McClelland’s (1961) motivational needs theory was closely related to Herzberg’s work. McClelland identified three types of motivational need (Box 5.2) which he proposed were found to varying degrees in all workers and managers. He suggested that the dominant need or needs within given individuals would influence their management style and behaviours, as well as affecting how they are motivated and how they motivate others. The three motivational needs are illustrated in Box 5.2.

Veterinary business management

an ethical approach to managing people and practices

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Introduction

Business ethics

Part I: Management theory

Management styles

Human resource management

Management theory and motivation

Veterinary business management: an ethical approach to managing people and practices