Urinary tract298

URINARY TRACT

KIDNEYS

11.1. NON-VISUALIZATION OF THE KIDNEYS

11.2. VARIATIONS IN KIDNEY SIZE AND SHAPE

11.3. VARIATIONS IN KIDNEY RADIOPACITY

11.4. VARIATIONS IN KIDNEY LOCATION

11.5. UPPER URINARY TRACT CONTRAST STUDIES: TECHNIQUE AND NORMAL APPEARANCE

Preparation

Side effects

Bolus intravenous urogram (low volume, high concentration)

Infusion intravenous urogram (large volume, low concentration): an alternative technique for the ureters

Ultrasound-guided antegrade pyelography

11.6. ABSENT NEPHROGRAM

11.7. ABNORMAL TIMING OF THE NEPHROGRAM

(After Feeney, D.A., Barber, D.L. and Osborne, C.A., 1982, Functional aspects of the nephrogram in excretion urography: a review. Veterinary Radiology 23, 42–45, with permission.)

Initial Opacification

Subsequent Opacification

Good

Progressive decrease

Normal

Fair to good

Progressive increase

Systemic hypotension induced by the contrast medium

Contrast medium-induced renal failure

Acute renal obstruction

Fair to good

Persistent

Systemic hypotension induced by the contrast medium

Contrast medium-induced renal failure

Acute tubular necrosis

Poor

Progressive decrease

Insufficient contrast medium dose

Primary polyuric renal failure

Intravenous fluids given during the procedure

Poor

Progressive increase

Systemic hypotension prior to contrast medium administration

Renal ischaemia

Acute extrarenal obstruction

Poor

Persistent

Primary glomerular dysfunction

Severe acute or chronic renal disease

Slow opacification of abnormal and poorly vascularized tissue

None

None

Insufficient contrast medium dose

Prior nephrectomy or non-functional kidney

Renal aplasia

Arterial obstruction or traumatic avulsion of renal artery

11.8. UNEVEN RADIOPACITY OF THE NEPHROGRAM

11.9. ABNORMALITIES OF THE PYELOGRAM

11.10. ULTRASONOGRAPHIC EXAMINATION OF THE KIDNEYS

11.11. NORMAL ULTRASONOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE OF THE KIDNEYS

11.12. ABNORMALITIES OF THE RENAL PELVIS ON ULTRASONOGRAPHY

11.13. FOCAL PARENCHYMAL ABNORMALITIES OF THE KIDNEY ON ULTRASONOGRAPHY

11.14. DIFFUSE PARENCHYMAL ABNORMALITIES OF THE KIDNEY ON ULTRASONOGRAPHY

11.15. PERIRENAL ABNORMALITIES ON ULTRASONOGRAPHY

URETERS

11.16. DILATED URETER

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Urogenital tract

Kidneys298

11.1 Non-visualization of the kidneys299

11.2 Variations in kidney size and shape299

11.3 Variations in kidney radiopacity300

11.4 Variations in kidney location301

11.5 Upper urinary tract contrast studies: technique and normal appearance301

11.6 Absent nephrogram303

11.7 Abnormal timing of the nephrogram303

11.8 Uneven radiopacity of the nephrogram303

11.9 Abnormalities of the pyelogram304

11.10 Ultrasonographic examination of the kidneys305

11.11 Normal ultrasonographic appearance of the kidneys305

11.12 Abnormalities of the renal pelvis on ultrasonography306

11.13 Focal parenchymal abnormalities of the kidney on ultrasonography306

11.14 Diffuse parenchymal abnormalities of the kidney on ultrasonography307

11.15 Perirenal abnormalities on ultrasonography307

Urinary bladder310

11.19 Non-visualization of the urinary bladder310

11.20 Displacement of the urinary bladder310

11.21 Variations in urinary bladder size311

11.22 Variations in urinary bladder shape311

11.23 Variations in urinary bladder radiopacity311

11.24 Urinary bladder contrast studies: technique and normal appearance312

11.25 Reflux of contrast medium up a ureter following cystography313

11.26 Abnormal bladder lumen on cystography313

11.27 Thickening of the urinary bladder wall on cystography314

11.28 Ultrasonographic examination of the bladder315

11.29 Normal ultrasonographic appearance of the bladder315

11.30 Thickening of the bladder wall on ultrasonography315

11.31 Changes in echogenicity of the bladder wall316

11.32 Cystic structures within or near the bladder wall on ultrasonography316

11.33 Changes in urinary bladder contents on ultrasonography316

Female genital tract319

Uterus320

11.41 Uterine enlargement320

11.42 Variations in uterine radiopacity321

11.43 Radiographic signs of dystocia and fetal death321

11.44 Ultrasonographic examination of the uterus322

11.45 Normal ultrasonographic appearance of the uterus322

11.46 Variation in uterine contents on ultrasonography322

11.47 Thickening of the uterine wall on ultrasonography322

Male genital tract322

Prostate322

11.48 Variations in location of the prostate323

11.49 Variations in prostatic size323

11.50 Variations in prostatic shape and outline324

11.51 Variations in prostatic radiopacity324

11.52 Ultrasonographic examination of the prostate324

11.53 Normal ultrasonographic appearance of the prostate324

11.54 Focal parenchymal changes of the prostate on ultrasonography325

11.55 Diffuse parenchymal changes of the prostate on ultrasonography325

11.56 Paraprostatic lesions on ultrasonography325

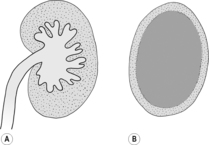

The kidneys lie in the retroperitoneal space, and visualization of the renal outline depends on the presence of sufficient surrounding fat. In the dog, the cranial pole of the right kidney lies in the renal fossa of the caudate lobe of the liver at the level of T13–L1 and may be difficult to discern, especially in thin or deep-chested dogs or if the gastrointestinal tract contains much ingesta. The left kidney usually lies approximately half a kidney length more caudally, and more ventrally, and is more mobile. The kidneys are best seen on a right lateral recumbent expiratory film, in which the dependent right kidney slides cranially and there is least superimposition. They are bean-shaped, with a hilar notch where the vessels and ureters enter; depending on their orientation relative to the X-ray beam, they may be seen as either ovoid or bean-shaped structures. In lateral recumbency, the dependent kidney usually appears ovoid, whereas the uppermost kidney droops so that the hilus is profiled and the kidney appears bean-shaped.

In cats, the kidneys tend to be more easily visible, as the right kidney is usually separated from the liver by fat and both kidneys are mobile. The kidneys appear smaller, rounder and more variable in location than in the dog. On a lateral view, partial superimposition of the kidneys may mimic a smaller mass in both cats and dogs.

Kidney size is best assessed on a ventrodorsal (VD) radiograph to avoid a difference between the two kidneys due to magnification of the uppermost one, which may occur in lateral recumbency (Fig. 11.1). Measurements should be made on plain films, as the kidneys swell slightly during an intravenous urogram (IVU), the increase in size being dose- and time-dependent. The size range of the canine kidney is usually quoted as 2.5–3.5 times the length of L2, although 2.75–3.25 may be more realistic; the normal feline kidney size range is 1.9–2.6 times the length of L2 in neutered cats and 2.1–3.2 in entire cats. The two kidneys should be the same size in a given patient.

1. Normal variant (especially for the right kidney on a VD view).

a. Inappropriate exposure setting or processing (especially underexposure).

b. Little abdominal fat.

– Young animals.

– Very thin animals.

c. Deep-chested conformation, kidneys therefore lying more cranially.

d. Food, gas or faeces in the gastrointestinal tract, obscuring a kidney.

2. Kidney in abnormal location (see 11.4).

3. Nephrectomy.

4. Very small kidney (see 11.2.5).

5. Renal agenesis.

a. Unilateral (either right or left may be absent), with compensatory hypertrophy of the remaining kidney; the ureter may still be present.

b. Bilateral – rare; animal dies soon after birth.

6. Severe peritoneal effusion.

7. Retroperitoneal disease.

a. Urine leakage.

b. Haemorrhage.

c. Inflammation.

d. Diffuse neoplasia.

1. Normal size kidney, smooth outline.

a. Normal.

b. Acute nephritis.

c. Acute renal toxicity.

– Ethylene glycol (antifreeze) poisoning.

– Other toxins.

– Certain drugs (e.g. gentamicin, cisplatin).

d. Amyloidosis.

e. Early stages of other disease processes.

2. Normal size kidney, irregular outline.

a. Disease processes listed below that have not produced a detectable size change.

b. Renal infarct.

c. Trauma.

3. Mildly enlarged kidney, smooth outline.

a. Nephrogram phase of IVU – bilateral.

b. Acute renal failure – bilateral; numerous causes.

c. Acute glomerulo- or interstitial nephritis – often bilateral.

d. Acute pyelonephritis – often bilateral.

e. Hydronephrosis – unilateral or bilateral, depending on the cause.

f. Congenital portosystemic shunts – dogs often show bilateral kidney hypertrophy ± urinary tract calculi and haematogenous osteomyelitis.

g. Compensatory renal hypertrophy – unilateral; opposite kidney small or absent.

h. Renal neoplasia – usually unilateral; more often irregular than smooth (other than lymphoma); in cats, lymphoma is the commonest renal tumour and is usually bilateral.

i. Subcapsular abscess, haematoma or urine – unilateral or bilateral depending on the cause.

j. Perirenal fluid associated with acute renal failure.

k. Amyloidosis – often bilateral.

l. Acromegaly – bilateral.

m. Parasitic – Dioctophyma renale* infection.

n. Hypertrophic feline muscular dystrophy – bilateral.

5. Enlarged kidney, irregular outline.

a. Primary renal neoplasia – usually unilateral but may be bilateral; benign and malignant neoplasms cannot be differentiated on radiographic appearance alone.

– Renal cell carcinoma.

– Transitional cell carcinoma.

– Nephroblastoma; usually young dogs.

– Hereditary multifocal renal cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma (see p. 306) – usually German Shepherd dogs, together with nodular dermatofibrosis lesions and uterine leiomyomas.

– Renal lymphoma – especially cats, bilateral; often other organs are affected too, and there is an association with nasal lymphoma.

– Others: adenoma, haemangioma, haemangiosarcoma, papilloma, anaplastic sarcoma, extraskeletal osteosarcoma, etc.

b. Metastatic neoplasia – unilateral or bilateral.

– Metastasis from a primary in the opposite kidney.

– Many other primary tumours metastasize to the kidneys.

c. Renal abscess – usually unilateral.

d. Renal haematoma – usually unilateral.

e. Renal granuloma – unilateral or bilateral.

f. Renal cyst(s).

g. Renal hamartoma – a benign, focal malformation that may cause renal haemorrhage.

h. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) – heritable condition in long-haired cats, especially Persians and Persian crosses, and also in Cairn and Bull Terriers; usually bilateral.

i. Cats – FIP, causing pyogranulomatous nephritis.

6. Small kidney, smooth or irregular in outline.

a. Chronic renal disease.

– Chronic glomerulonephritis.

– Chronic pyelonephritis.

– Chronic interstitial nephritis.

– Chronic renal calculi.

b. Developmental renal hypoplasia or dysplasia – younger dogs, with a familial tendency in some breeds, including Cocker Spaniel, Lhasa Apso, Shih Tzu, Norwegian Elkhound, Samoyed, Boxer and Dobermann.

c. Chronic hydronephrosis.

d. Parenchymal atrophy secondary to renal infarcts.

e. Amyloidosis, especially in cats.

The radiopacity of the kidneys is normally the same as for other soft tissue structures. On VD radiographs, a slight radiolucency may be observed in the central medial area of each kidney due to fat within the pelvic region. Incidental adrenal gland mineralization in older cats should not be mistaken for renal changes.

1. Focal increased radiopacity of the kidney – mineralization of parenchyma may be differentiated from renal pelvic calculi by means of IVU, as the latter will be obscured by the pyelogram.

a. Artefactual due to superimposition of the other kidney (lateral view), nipple (VD view) or ingesta (either view).

b. Mineralized nephroliths in the renal pelvis – large ones can become staghorn in shape; ureteric calculi may also be seen.

c. Mineralized nephroliths in the renal diverticula – often multiple (especially in cats).

d. Dystrophic mineralization of parenchyma.

– Neoplasia.

– Chronic haematoma, granuloma, cyst or abscess.

f. Osseous metaplasia.

2. Diffuse or multifocal increased radiopacity of the kidney – nephrocalcinosis.

a. Chronic renal disease.

b. Ethylene glycol (antifreeze) poisoning.

c. Hyperparathyroidism – primary or secondary.

d. Hyperadrenocorticism.

e. Hypercalcaemia syndromes.

f. Nephrotoxic drugs (e.g. gentamicin).

g. Hypervitaminosis D.

h. Renal telangiectasia – Corgi.

3. Reduced radiopacity of the renal pelvis.

a. Pelvic fat, especially in obese cats.

b. Reflux of air from the urinary bladder under high pressure during pneumocystography; gas lucency may also be seen in the ureters.

– Overinflation of a normal bladder.

– Inflation of a poorly distensible bladder.

c. Inadvertent catheterization of an ectopic ureter followed by air injection.

d. Infection with gas-producing bacteria.

Both congenital and acquired causes of abnormal location occur. The majority are acquired, due to displacement by masses or through ruptures. Congenital malposition constitutes renal ectopia and is unusual.

1. Cranial displacement.

a. Intrathoracic; right kidney herniation following diaphragmatic rupture is reported in cats.

b. By large mid- or caudal abdominal mass.

2. Caudal displacement.

a. Due to intrathoracic expansion.

b. By distended stomach.

c. Left kidney by mass in head of spleen.

d. Right kidney by hepatomegaly.

e. Ectopic kidney (e.g. sublumbar).

f. Situs inversus of abdominal organs – right kidney caudal to left kidney.

3. Ventral displacement.

a. By retroperitoneal fat in obese animal.

b. By pathological retroperitoneal swelling or effusion (see 9.9).

c. By ipsilateral adrenal mass (cranial pole usually displaced more than caudal pole).

d. Large renal masses may lie more ventrally than normal due to gravity.

e. Ectopic kidney in peritoneal cavity.

4. Dorsal displacement.

a. By ventral abdominal mass.

5. Lateral displacement.

a. By ipsilateral adrenal mass (cranial pole usually displaced more than caudal pole).

6. Medial displacement.

a. Simple renal ectopia – kidney, ureter and vesicoureteral junction are on the same side of the abdomen.

b. Crossed renal ectopia – kidney lies on the opposite side to normal, but the ureter crosses the midline; may be fused to contralateral kidney.

c. Horseshoe kidney – both kidneys medially displaced and fused together.

Indications for contrast studies of the kidneys and ureters include the following:

• Identification of number, location, size and shape of the kidneys; some information is given about kidney function and internal architecture, especially of the renal pelvis.

• Investigation of abdominal masses.

• Investigation of haematuria or pyuria not arising from the lower urogenital tract.

• Investigation of the location of possible urinary tract calculi, and differentiation from gastrointestinal material.

• Investigation of urinary incontinence.

• After trauma with suspected urinary tract damage.

Intravenous urography or IVU (excretion urography) is especially useful for evaluation of the renal pelvis and ureters. Lesions of the renal parenchyma are more difficult to diagnose, and generally such diseases are more readily detected by ultrasonography. Selective renal angiography is not often performed; contrast medium deposited near the renal artery via a femoral arterial catheter will outline the renal blood supply and demonstrate features of kidneys that are failing and therefore not likely to opacify well following an IVU.

During and for a few seconds immediately after the contrast medium injection, the vascular supply to the kidney is outlined, forming the angiogram phase. This is quickly followed by a diffuse increase in radiopacity of the kidney parenchyma, the nephrogram phase. Occasionally, the cortex transiently appears more radiopaque than the medulla; the medulla is approximately twice the thickness of the cortex. The nephrogram persists for about 1–3 h. Within 1–2 min of the injection in normal kidneys, the renal pelvis and ureters are filled by contrast medium, which is being concentrated in the urine; this is the pyelogram phase (Fig. 11.2). The radiographic appearance of the renal pelvis is very variable in dogs, and the renal diverticula are not consistently seen.

• Blood tests: blood urea nitrogen level > 17 mmol/L (> 100 mg%) and/or blood creatinine levels > 350 μmol/L (> 4 mg%) indicate severe renal compromise, which is likely to preclude opacification of the upper urinary tract and is a contraindication for the study (if the urea and creatinine are only moderately increased, consideration should be given to increasing the dose of iodine up to two-fold to improve visualization of the urinary system).

• Assessment of circulation and hydration status: injection of hypertonic contrast medium should not be made in patients that are dehydrated or in hypotensive shock in case of induction of acute renal shut-down. Non-ionic (low-osmolar) iodinated contrast media are safer for such patients and for cats.

• Twelve-hour fast and colonic enema.

• Placement of an intravenous catheter, because extravasation of contrast medium outside the vein is irritant.

• Sedation or anaesthesia of the patient, as appropriate.

• Plain (survey) lateral and VD radiographs to check patient preparation and exposure factors.

• Induction of dehydration.

• Acute renal failure due to precipitation of proteins in renal tubules (more likely if the urine protein is elevated).

• Rare anaphylactic shock (severe reaction or death).

Inject up to 850 mg I/kg of body weight of 300–400 mg I/mL contrast medium rapidly with the patient in dorsal recumbency; take an immediate VD radiograph (the kidneys are seen separately, as they are not superimposed) followed by laterals and VDs as necessary. Identify the angiogram, nephrogram and pyelogram phases of opacification. Caudal abdominal compression to occlude the ureters and increase pelvic filling has been described, although this can produce the artefactual appearance of mild hydronephrosis.

Inject approximately 1200 mg I/kg of body weight of 150 mg I/mL contrast medium slowly as a drip infusion; this creates more osmotic diuresis and better visualization of the ureters. Rapid radiographic exposure is not necessary. Only the nephrogram and pyelogram phases are seen. It is particularly important to ensure that the colon is empty of faeces, and performing a pneumocystogram first will increase bladder pressure and improve opacification of the ureters as well as providing a radiolucent background against which ureter endings are easier to see. Both right and left lateral recumbent and oblique views as well as VDs are helpful for identification of ureter terminations, and fluoroscopy may also be useful.

This technique permits assessment of the pelvis and ureters in animals with obstructive uropathy, which are anuric or oliguric and in which an IVU is likely to be non-diagnostic. Under ultrasound guidance, a small amount of positive contrast medium is injected into the renal pelvis and opacifies the ureters as far distally as any obstruction. Nephropyelocentesis is also possible, of value in the diagnosis of pyelonephritis.

1. Inadequate dose of contrast medium.

2. Severe renal disease with marked azotaemia.

3. Prior nephrectomy.

4. Very small kidney overlooked.

5. Renal aplasia.

6. Obstructed or avulsed renal artery.

7. Absence of functional renal tissue.

a. Extensive neoplasia.

b. Extreme hydronephrosis.

c. Large abscess.

The normal appearance is of uniformly increased kidney radiopacity and improved visualization of kidney outline, which occurs due to the presence of contrast medium in the renal vasculature and tubules. The opacity should be greatest initially, followed by a gradual decrease. Abnormalities in timing are shown in Table 11.1.

• Neoplasia

• Abscess

• Granuloma

• Haematoma

• Cyst

Areas of poor vascularity show initial absent or poor opacification, but there may be variable increase with time.

1. Well-defined areas of non-opacification.

a. Renal cyst – solitary cysts are an occasional incidental finding.

b. Renal abscess, granuloma or haematoma.

c. Renal infarct – single or multiple; wedge-shaped area with the apex directed towards the hilus.

d. Polycystic kidney disease – heritable condition in long-haired cats, especially Persians and Persian crosses, and also in Cairn and Bull Terriers; usually bilateral.

e. Hereditary multifocal renal cystadenoma or carcinoma – usually German Shepherd dogs, together with nodular dermatofibrosis lesions and uterine leiomyomas.

2. Poorly defined areas of non-opacification.

a. Renal neoplasia (may also see areas of increased opacity due to contrast medium extravasation and pooling).

– Renal cell carcinoma.

– Transitional cell carcinoma.

– Nephroblastoma.

– Renal adenoma, haemangioma or papilloma.

– Anaplastic sarcoma.

– Hereditary multifocal renal cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma – German Shepherd dog.

– Renal lymphoma – especially cats, bilateral; often wedge-shaped areas of reduced opacification.

b. Renal infarct – may be ill defined.

c. Severe nephritis.

d. Cats – FIP.

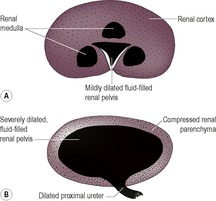

3. Peripheral rim of opacification only – severe hydronephrosis (Fig. 11.3B).

4. Peripheral rim of non-opacification.

a. Subcapsular fluid accumulation (e.g. perirenal pseudocysts, acute renal failure, urinoma).

b. Cats – subcapsular lymphoma.

5. Areas of increased opacity due to accumulation of contrast medium.

a. Neoplasia.

b. Hamartoma.

c. Leaking blood vessel (often the cause of ‘idiopathic’ renal haemorrhage).

d. Trauma.

6. Extravasation of contrast medium outside the kidney shadow.

a. Trauma.

The pyelogram (demonstrating renal diverticula, pelvis and ureters) should be visible approximately 1 min after the injection and persists for up to several hours. In the dog, the pelvis is usually ≤ 2 mm wide and diverticula ≤ 1 mm wide; figures are not available for cats.

1. Dilation of the renal pelvis ± diverticula.

a. Caudal abdominal compression used.

b. Physiological due to polyuria and polydipsia or intravenous fluid therapy.

c. Diuresis due to hyperosomolar contrast medium, fluid therapy or drugs – bilaterally symmetrical and usually mild.

d. Hydronephrosis – pelvic dilation may become very gross, with only a thin rim of surrounding parenchymal tissue (Fig. 11.3).

e. Renal calculus (radiopaque calculi may be obscured by the similar radiopacity of the contrast medium).

f. Chronic pyelonephritis or pyonephrosis – filling defects may also be seen due to debris, and mild hydroureter may be present; often pelvis dilated only, not diverticula; ± irregular pelvic outline.

g. Renal neoplasia.

– Secondary dilation of the pelvis and proximal ureter is often seen.

– Mechanical obstruction of the pelvis.

h. Ectopic ureter – due to stenosis of the ureter ending and/or ascending infection (see 11.16.1 and Fig. 11.8).

i. Renal pelvic blood clot.

– Coagulopathy.

– Bleeding neoplasm.

– Trauma.

– After renal biopsy or antegrade pyelography.

– Idiopathic renal haemorrhage.

j. Dioctophyma renale* (giant kidney worm).

2. Distortion of the renal pelvis.

b. Other renal parenchymal mass lesions (cyst, abscess, haematoma, granuloma).

c. Large renal calculus.

d. Chronic pyelonephritis.

e. Blood clot.

– Coagulopathy.

– Bleeding neoplasm.

– Trauma.

– After renal biopsy or antegrade pyelography.

– Idiopathic renal haemorrhage.

f. Polycystic kidney disease – heritable condition in long-haired cats, especially Persians and Persian crosses, and also in Cairn and Bull Terriers; usually bilateral.

3. Filling defects in the pyelogram.

a. Normal interlobar blood vessels – linear radiolucencies within the diverticula.

b. Air bubbles refluxed from overdistended pneumocystogram.

c. Calculi.

d. Debris due to pyelonephritis.

e. Neoplasia.

f. Blood clot.

g. Dioctophyma renale* (giant kidney worm).

The kidneys may be examined from either a ventral abdominal or a flank approach. The advantages of the latter approach include the superficial location of the kidneys and the absence of intervening bowel. The main disadvantage is that the clipped areas of flank may be less acceptable to the owner.

A high-frequency (7.5 MHz) transducer should be used. Each kidney should be imaged in the transverse and either sagittal or dorsal (coronal) section, ensuring that the entire renal volume is examined. Where possible, the renal artery and vein entering and leaving the hilus should be identified.

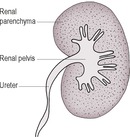

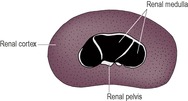

The normal kidney is smooth and bean-shaped. A thin, echogenic capsule may be visible except at the poles, where the tissue interfaces are parallel to the ultrasound beam. The renal cortex is hypoechoic and finely granular in texture (Fig. 11.5). It is usually isoechoic or slightly hypoechoic relative to the liver if a 5 MHz transducer is used, but may appear mildly hyperechoic relative to the liver with a 7.5 MHz transducer or higher. The renal cortex should normally be less echogenic than the spleen. The renal medulla is usually virtually anechoic and divided into segments by the echogenic diverticula and interlobar vessels. A linear hyperechoic zone has been described, lying parallel to the corticomedullary junction in the medulla of some normal cats (medullary rim sign). Echogenic specks at the corticomedullary junction represent arcuate arteries. Fat in the renal sinus forms an intensely hyperechoic region at the hilus, which may cast a faint acoustic shadow.

The kidney size may be measured ultrasonographically, and normal size ranges are given for cats, being 37–44 mm long (the right kidney may be slightly larger than the left). In dogs, kidney size varies with body weight. The ratio of kidney length to aortic diameter may be calculated: renal size is considered to be reduced if kidney:aorta is < 5.5 and to be increased if kidney:aorta is > 9.1.

An increase in renal cross-sectional area is a sensitive indicator of acute renal allograft rejection in dogs and cats.

Causes of renal pelvic abnormalities are listed in Section 11.9, Abnormalities of the pyelogram, and the same principles apply to ultrasonography.

1. Pelvic dilation, leading to hydronephrosis – an anechoic accumulation of fluid is seen in the renal pelvis; as the severity of the dilation increases, there is progressive compression of the surrounding renal parenchyma (Fig. 11.6) and there may be associated ureteral dilation.

2. Distortion of the renal pelvis – less easy to recognize on ultrasonography than with an IVU.

3. Material within the pelvis, such as inflammatory debris, blood clots, neoplasm or calculi, result in masses of variable size and echogenicity; in the case of renal calculi, there is a strongly reflective surface with distal acoustic shadowing, irrespective of mineral composition. Multiple ring-like structures, 5–10 mm in diameter, have been described in the renal pelvis in Dioctophyma renale* infection in the dog.

1. Well-circumscribed, anechoic parenchymal lesion; simple or complex.

a. Thin, smooth wall.

– Cyst – single or multiple. PKD is heritable in long-haired cats, mainly Persians and Persian crosses, and also in Cairn and Bull Terriers, and may be associated with foci of mineralization and an indistinct corticomedullary junction. Cysts are also seen in familial nephropathy of Shih Tzus and Lhasa Apsos; solitary cysts may be seen in other breeds as incidental findings.

– Hereditary multifocal renal cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma – complex, cystic structures; usually German Shepherd dogs, together with nodular dermatofibrosis lesions and uterine leiomyomas.

2. Hypoechoic parenchymal lesion.

a. Neoplasia.

– Lymphoma (nodular or wedge-shaped).

– Malignant histiocytosis (although more commonly there is involvement of the liver, spleen and lymph nodes).

– Mast cell infiltration.

– Others (see 11.2.4).

3. Hyperechoic parenchymal lesion.

a. Neoplasia.

– Primary tumour containing blood or mineralization (e.g. haemangioma, chondrosarcoma).

– Lymphoma.

– Metastatic (e.g. haemangiosarcoma, thyroid adenocarcinoma).

b. Chronic infarct (wedge-shaped).

c. Parenchymal calcification or calculus.

d. Parenchymal gas.

e. A large number of very small cysts (Polycystic disease, PKD) – especially Persian and Persian cross cats; also reported in Cairn and Bull Terriers.

f. Cats – FIP.

4. Heterogeneous or complex parenchymal lesion.

a. Neoplasia.

b. Abscess.

c. Haematoma.

d. Granuloma.

e. Acute infarct.

f. A large number of very small cysts (PKD) – especially Persian and Persian cross cats; also reported in Cairn and Bull Terriers.

5. Medullary rim sign – an echogenic line in the outer zone of the renal medulla that parallels the corticomedullary junction.

a. Normal variant.

b. Nephrocalcinosis, hypercalcaemic nephropathy.

c. Ethylene glycol (antifreeze) toxicity.

d. Chronic interstitial nephritis.

e. Lymphoma.

f. Acute tubular necrosis.

g. Portosystemic shunt.

h. Leptospirosis.

i. Mineral deposit in tubule lumen.

j. Cats – FIP.

6. Acoustic shadowing.

a. Deep to pelvic fat.

b. Renal calculus – strongly reflective surface.

c. Nephrolithiasis – reflective surface.

d. Dystrophic mineralization of a chronic abscess or neoplasm.

e. Gas.

Corticomedullary definition may be increased or decreased, depending on whether only the cortex or both cortex and medulla are affected.

1. Increased cortical echogenicity, with retained or enhanced corticomedullary definition.

a. Normal variant in cats (fat deposition in the tubules).

b. Inflammatory disease.

– Glomerulonephritis.

– Interstitial nephritis.

– Cats – FIP.

c. End-stage renal disease – kidney also small and irregular.

d. Acute tubular necrosis or nephrosis due to toxins, for example ethylene glycol (antifreeze) toxicity.

e. Renal dysplasia – kidney also small and irregular.

f. Nephrocalcinosis, hypercalcaemic nephropathy.

g. Neoplasia.

– Diffuse lymphoma (especially cats).

– Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma.

h. Amyloidosis.

2. Reduced corticomedullary definition.

a. Chronic renal disease (end-stage kidneys).

b. Renal dysplasia.

c. Multiple small cysts.

Abnormal perirenal material may be identified on ultrasonography or IVU. On ultrasonography, the material is usually anechoic to hypoechoic but in some cases contains debris or is complex in echogenicity. Sonographically, subcapsular fluid may be difficult to distinguish from perirenal retroperitoneal fluid (Fig. 11.7), and both types of abnormality are considered in this section.

1. Perirenal or perinephric pseudocyst – especially elderly cats, usually unknown aetiology, although in one cat transitional cell carcinoma affecting the capsule was identified. Usually large amounts of unilateral or bilateral anechoic, subcapsular transudate. The kidneys are also often abnormal.

2. Perirenal abscess – affects cats more often than dogs; usually associated with pyelonephritis. Anechoic to hypoechoic perirenal fluid containing small specks of echogenic debris; usually unilateral.

3. Perirenal haemorrhage – unilateral or bilateral, depending on cause.

a. Trauma.

b. After renal biopsy.

c. Coagulopathy.

d. Neoplastic erosion of a blood vessel.

e. Chronic expanding haematoma (rare) – complex sonographic appearance.

4. Neoplasia.

a. Renal lymphoma in cats – a subcapsular hypoechoic rim is due to lymphoma infiltrate rather than free fluid; usually bilateral.

b. Transitional cell carcinoma has been reported as producing unilateral subcapsular transudate in a cat.

5. Urinoma – anechoic fluid, secondary to rupture of the kidney or proximal ureter; usually unilateral.

6. Acute renal failure – anechoic fluid, ± renal abnormalities depending on the cause; usually bilateral.

7. Retroperitoneal fluid secondary to trauma or urethral obstruction with very full bladder.

The ureters lie in the retroperitoneal space until they approach the bladder, where they enter the peritoneal cavity. They are not normally visible on plain radiographs unless they are markedly dilated, although occasionally they may be seen as fine, radiopaque lines in obese animals. An IVU or ultrasound-guided antegrade pyelography is required for the assessment of ureteric location, diameter, patency and integrity (see 11.5). Retrograde (vagino)urethrography is also helpful in demonstration of ectopic ureter endings. Normal ureters move urine to the bladder in peristaltic waves, so their diameter is variable and the entire ureter may not be visible on a single IVU radiograph. The normal termination of the ureter within the bladder wall is characteristically hook-shaped, the right normally lying slightly more cranially than the left (Fig. 11.8). IVU with CT is an excellent imaging modality for evaluation of the ureters.

Dislodged nephroliths may lead to ureteral obstruction and dilation but are easily mistaken for radiopaque bowel contents on plain radiographs. They may be obscured by contrast medium on IVU (confirming their location) or seen as filling defects. The osmotic diuresis caused by an IVU may also flush the calculi into the bladder.

Traumatic rupture of a ureter will result in uroretroperitoneum and/or uroabdomen with loss of visualization of retroperitoneal and/or abdominal detail. IVU shows contrast medium leakage; the site of leakage may be hard to identify, but the proximal ureter is likely to be dilated and hydronephrosis may ensue. Perirenal or paraureteral urinoma (uriniferous pseudocyst) is an occasional sequel, being a retroperitoneal accumulation of extravasated urine in a thick, fibrous sac. It is usually associated with ipsilateral hydronephrosis.

Not seen on plain radiographs unless the dilation is gross; otherwise requires an IVU or ultrasound-guided antegrade pyelography for demonstration (see 11.5). The normal canine ureter seen on an IVU is ≤ 3 mm in diameter, depending on the dog’s size; ureters are very fine in the cat. Dilation of a ureter with urine due to obstruction is known as hydroureter.

1. Ectopic ureter – dilation due to stenosis at the ectopic ending and/or ascending infection (Fig. 11.8); unilateral or bilateral. The ureter usually opens into the urethra, occasionally vagina or rectum; the precise location may be shown using concomitant pneumocystogram and/or retrograde (vagino)urethrogram. In dogs, the ureter usually tunnels through the bladder wall to its ending, whereas in cats the ectopic ureters usually bypass the bladder. Absence of bladder opacification suggests that both ureters are ectopic, but the converse does not apply because urine from an ectopic ureter ending may seep cranially into the bladder. The ipsilateral kidney may be small and/or irregular, with hydronephrosis and associated pyelonephritis.

a. Congenital – females usually show incontinence from a young age, although males may remain continent due to the longer urethra; females are affected more often than males, dogs more often than cats (especially Golden and Labrador Retrievers).

b. Acquired (e.g. accidental ligation of the ureters with the uterine stump at ovariohysterectomy, leading to ureterovaginal fistula).

2. Ascending infection (the ureters may also be narrow and/or lacking peristalsis) – pyelonephritis may also be present, causing pelvic dilation and filling defects ± irregularity of the kidney outline.