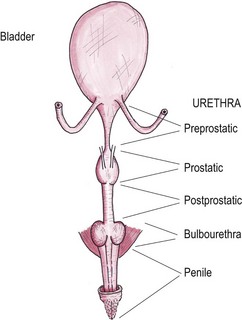

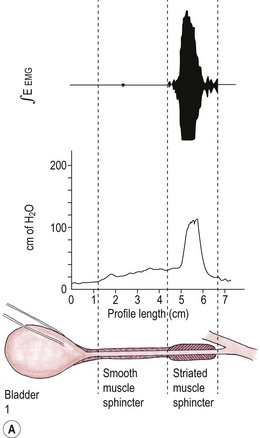

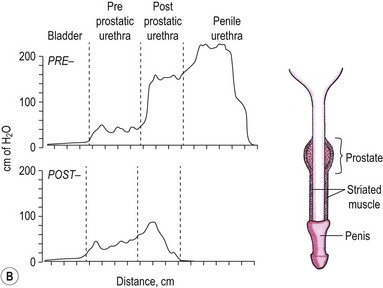

Chapter 38 The urethra extends from the trigone of the bladder to the urethral meatus or orifice. The cranial two-thirds of the female urethra is covered by detrusor fibers, connective tissue, and smooth muscle which comprises the internal urethral sphincter; the caudal third of the urethra is initially encircled by striated urethralis muscle, which comprises the external urethral sphincter. In the caudal urethra, the urethralis muscle expands dorsally and encircles both the vagina and urethra. The urethral smooth muscle contains circular fibers which act as a sphincter and longitudinal fibers that contract to dilate the urethra. The epithelium changes from transitional to stratified squamous in the caudal quarter of the urethra.1 The male cat has an elongated bladder neck or preprostatic urethra, a short wider prostatic section, a postprostatic or pelvic section, and the distal penile urethra that narrows significantly at the glans (Fig. 38-1). Embryologically, the prostatic urethra is equivalent to the female urethra, the pelvic portion of the urogenital sinus forms the membranous portion, and the penile urethra is derived from the phallic portion of the sinus. The preprostatic urethra consists of epithelium, submucosa, and three layers of smooth muscle, which are continuous with the detrusor muscle at the vesicourethral junction. At the prostate, the muscle changes from smooth to striated fibers. The postprostatic urethra has circumferentially orientated striated muscle fibers, the urethralis muscle, which corresponds to the external urethral sphincter. This contributes to resting urethral tone but also contains fast twitch fibers that are capable of responding to sudden changes in vesicular pressure and thus maintaining continence during coughing or sudden movement.2 The muscle mass increases just caudally to the bulbourethral glands with the insertion of the ischiocavernosus muscles ventrally and the bulbocavernosus muscles dorsally. The penile urethra has longitudinally orientated muscle fibers ventrally but not dorsally; however, in this area the urethra is surrounded by highly vascular collagenous connective tissue and the corpus cavernosus dorsally.3 The epithelium of the male urethra is mainly transitional with stratified squamous epithelium near the urethral orifice.4 The male urethra is approximately 8.5–10.5 cm long3 and the dimensions of each part are shown in Figure 38-1. The urethral circumference is not affected by castration although fibrocyte density increases with castration.4 In the female, the urethral blood supply is via the vaginal arteries from the urogenital artery. The functional anatomy of the feline urethra has been studied experimentally by urethral pressure profile measurements.3,5,6 Urethral tone results from the interaction of the smooth muscle, striated skeletal muscle, fibroelastic and vascular tissue. The smooth muscle offers most resistance to urine leakage in the non-voiding animal. The external urethral sphincter is maintained at a low tone but activates with sudden increases in intra-abdominal or intravesicular pressure rises. The external urethral sphincter tone increases in response to fluid flow along the urethra or distension of the urethra. In the female, the maximal urethral closure pressure is predominantly in the distal third of the urethra at the level of the urethralis muscle6 (Fig. 38-2A). Interestingly, unlike in the dog, there have been no significant differences found in the urethral pressure profiles of intact and ovariectomized females.6 Figure 38-2 (A) Urethral pressure profile of the female cat. (B) Urethral pressure profile of the male cat. ([A] From Gregory CR, Willits NH. Electromyographic and urethral pressure evaluations: Assessment of urethral function in female and ovariohysterectomized female cats. American Journal of Veterinary Research 1986;47:1472, with permission; [B] from Gregory CR, et al, Electromyographic and urethral pressure profilometry: Assessment of urethral function before and after perineal urethrostomy in cats. American Journal of Veterinary Research 1984;45:2062–5, 1984. http://avmajournals.avma.org/loi.ajvr with permission.) In the male, the urethral pressure profiles reveal a pressure peak at the prostatic and early postprostatic urethra followed by high-pressure peaks in the bulbourethral and penile areas that usually have the maximal urethral closure pressure (Fig. 38-2B). The prostatic and postprostatic pressure peaks arise at the level of the urethralis muscle and the external urethral sphincter whilst the penile increase in urethral pressure results from the small diameter of the penile urethra. A combination of imaging modalities are used to evaluate the urethra. Urogenital radiographic studies, including contrast studies, are used to evaluate the integrity and diameter of the urethra. Prior to performing these radiographic studies, it is desirable that large intestinal content is minimal, which can be difficult to achieve in cats. Sodium citrate micro-enemas (Micralax, Micolette, Relaxit) should be used both on the evening prior to the investigation and on the morning of the investigation. The cat should be fasted overnight. If the colon is still impacted with feces, it is worth performing a warm water cleansing enema under anesthesia prior to radiography in order to achieve optimal results. For good quality radiographs, deep sedation or anesthesia is required. A positive contrast urethrogram or urethrocystogram is the best radiographic technique for evaluation of the urethra (Fig. 38-3). Urogenital radiographic studies, including contrast studies are described in chapter 8. Figure 38-3 A four-year-old male neutered domestic short-hair cat presented with recurrent lower urinary tract obstruction. A retrograde urethrocystogram is performed to ensure there is no narrowing proximal to the penile urethra that would contraindicate perineal urethrostomy. No narrowing is present in this cat. Female urethral catheterization is usually easier than the male and is aided by pulling the vulval lips caudally and then advancing a well lubricated 4 or 5 French balloon catheter along the ventral wall of the vagina (Fig. 38-4). Figure 38-4 Retrograde vaginourethrogram in a female cat with a normal urethra and ruptured bladder. In the male urethra, particularly in cats with feline lower urinary disease, a narrowing of the pelvic urethra is sometimes seen (Fig. 38-5). This is a symmetrical, smooth tapering and may be a result of prostatic compression, urethritis, or muscular spasm. It can be eliminated by antegrade urethrography or higher volume retrograde urethrography and should not be confused with a urethral stricture.7 This is a useful technique in the cat that can aid in diagnosing urethral masses, calculi, strictures, and tears. In the female (or male following perineal urethrostomy) biopsies can be taken using an endoscope with an instrument channel. Transurethral cystoscopy can be performed in the male cat using a flexible endoscope or prepubic percutaneous cystoscopy and urethroscopy. In cases with lower urinary tract disease, inflammation of the urethra and bladder wall can result in microtears of the mucosa and hemorrhage, which can obscure the examination. Cystoscopy is described in detail in Chapter 8. Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) encompasses urethral plugs (20–50%), feline interstitial cystitis (20–50%), bacterial cystitis (10–20%), and urolithiasis (10–20%).8–11 Cats at most risk of FLUTD are kept indoors, male, overweight, and fed on dried diets.12 Bacterial cystitis is more commonly seen in elderly cats with renal compromise which prevents concentration of the urine.13 Clinical signs of FLUTD include inappropriate urination, stranguria, hematuria, dysuria, and pollakiuria progressing to include various systemic signs (pain, bradycardia, depression, and vomiting) with complete obstruction. Males have a much higher risk of blocking. The diagnostic approach depends on the frequency and severity of episodes but should include urine analysis and culture even on first presentation. Obstructed cats require serum biochemistry profiles with electrolytes to allow stabilization of cases with hyperkalemia or marked azotemia prior to sedation or anesthesia. Risk factors for mortality include hypocalcemia and hyperkalemia.12 Many cases of FLUTD can be treated medically without resorting to surgery; however, recurrence rates after an episode of urethral obstruction are in the range of 30–40%, with obstruction rates being higher for urethral plugs.12 A 2002 multiple center study in North America reported a 70% reduction in perineal urethrostomy in a 20-year period from 1980–1999.13 This decrease in surgical management of FLUTD may reflect an improvement in medical treatment of the condition. However, if a cat has regular recurrence of urethral obstruction despite appropriate medical management, a perineal obstruction should be considered. In certain cases (e.g., if the owner is regularly away overnight) surgery can be considered earlier. In a study of 43 cats with urethral obstruction, 26% died or were euthanized because of their disease. Perineal urethrostomy was performed in 22% of cats and resulted in resolution of clinical signs in 50% of cases.14 Cats that had a perineal urethrostomy were half as likely to be euthanized due to their disease although this was a relatively small study. It is important to counsel owners, however, that if surgery is performed for obstructive cases of FLUTD the disease will still be present and further medical treatment may be required although re-obstruction is less likely to occur. Other complications reported following perineal urethrostomy include urinary tract infection, stricture formation, periurethral urine extravasation, and stoma dehiscence. The incidence of postoperative urinary tract infection is reported to be from 23–50%.15–18 The range in results may be due to the fact that the infections are often asymptomatic and self-limiting, though in chronic cases struvite urolithiasis can result.19 Urethral trauma may occur after blunt or penetrating injuries but is most commonly seen in males after traumatic urethral catheterization in cases of obstructed FLUTD.20,21 With iatrogenic catheter damage the frequent sites for damage are the distal penile urethra and the ischial arch. Damage at the level of the distal penile urethra (Fig. 38-6) is due to inadequate caudal straightening of the penile urethra prior to catheterization or an inadequately sedated or anesthetized cat. Damage at the ischial arch (Fig. 38-7) is likely due to a combination of the caudal traction on the penile urethra being maintained whilst the catheter is entering the postprostatic pelvic urethra and traumatic catheters, particularly those with a stylet still in place. With an obstructed cat hydropulsion via a urethral catheter rather than the catheter itself should be used to relieve the obstruction. Clinical signs of urethral rupture are listed in Box 38-1. Figure 38-6 Retrograde urethrogram showing rupture of the distal penile urethra secondary to traumatic urethral catheterization in a four-year-old domestic short-haired cat with obstructive FLUTD. Figure 38-7 Retrograde urethrogram of a ruptured urethra at the ischial arch demonstrating perforation of the colon by the catheter and subsequent colonogram in a six-year-old domestic long-haired cat with obstructive FLUTD. Cases of penile or postprostatic urethral rupture will often have urine leakage into the perineum and the dorsum around the tail base. If a fluctuant swelling is evident in these areas in a cat where there is a possibility of urethral rupture, the fluid should be drained with aspiration or placement of a small closed suction drain to prevent skin necrosis22,23 (Fig. 38-8). If the urethral rupture is further proximal, the urine will leak into the abdomen, resulting in uroabdomen and a chemical peritonitis, which will be septic if there was a pre-existing urinary tract infection present. Figure 38-8 (A) Skin slough secondary to a caudal urethral rupture and extravasation of urine around the tail base in a 10-month-old domestic short-haired cat that had a road traffic accident. (B) Retrograde urethrogram demonstrating this urethral rupture, with the contrast spreading around the tail base. The ability to urinate normally or pass a urinary catheter into the bladder does not exclude a urethral tear. Diagnosis is confirmed by imaging, including positive contrast urethrocystography. If contrast is seen both in the bladder and extravasating from the urethra a partial rupture is present. If no contrast agent is seen in the bladder the rupture can be partial or complete.24 Ultrasound examination may be useful to determine disruption of the proximal urethra and bladder neck. Biochemical analysis of blood, including electrolytes, should be checked prior to sedation or anesthesia to rule out hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, metabolic acidosis, or azotemia. If uroabdomen is present, abdominocentesis with biochemical analysis of the peritoneal fluid will support the diagnosis if the peritoneal creatinine, urea or potassium levels are higher than serum levels.25 Treatment options for urethral rupture include urinary diversion, primary repair, or proximal urethrostomy. Small lacerations will generally heal in three to five days with urinary diversion using an indwelling urethral catheter or cystostomy tube. Larger lacerations will heal if a strip of uroepithelium remains intact but strictures may result. In cases where catheterization is difficult, normograde placement of a catheter via a small cystostomy followed by placement of a guidewire aids retrograde placement of the urethral catheter.24 An indwelling catheter is required for up to three weeks depending on the size of the tear. Most lesions of the penile urethra in cats are treated by a perineal urethrostomy.20 Complete transection of the more proximal urethra is treated by urethral resection and anastomosis, which carries the risk of stricture formation, or a prepubic urethrostomy if the damage is severe. A vaginourethoplasty has recently been reported in a female cat after primary repair of a pelvic urethra rupture resulted in a stricture.26 Prognosis is worse for cats with multiple traumatic injuries.20 Complications which may occur after urethral rupture include strictures, incontinence, and urethrocutaneous fistulas. Urethral tumors are rare and more commonly seen in males than females. Affected cats tend to present later in life than those affected with FLUTD and often have a lean body condition. Presenting clinical signs include dysuria, hematuria, inappetence, constipation, and weight loss. Cases reported in the literature include a transitional cell carcinoma of the preprostatic urethra and a cat with leiomyoma.27,28 Prostatic tumors (usually carcinomas) are rare in the cat but can cause extramural obstruction.29 Urethral tumors generally carry a poor prognosis and due to their rarity effectiveness of treatment protocols is difficult to assess. Chemotherapeutic protocols including piroxicam, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide have been reported for urethral transitional cell carcinomas,30 but the few cases reported have had poor survival times. A case report of surgical excision of a transitional cell carcinoma followed by radiotherapy on recurrence had a survival time of over a year.27 Self-expanding metallic stents have been used in cases of urethral carcinoma but the survival times have been disappointing due to tumor occlusion of the stents.31,32

Urethra

Surgical anatomy

Female urethra

Male urethra

Blood supply

Functional anatomy

General considerations

Diagnostic imaging

Radiography

Cystoscopy

Surgical diseases

Feline lower urinary tract obstruction

Urethral trauma

Urethral tumors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine