15 Tumors of the Nasal and Paranasal Sinuses

On average, dogs with nasal cancer are about 10 years old, but nasal tumors have been reported in dogs younger than 1 year. Chondrosarcomas occur in younger dogs (mean, about 7 years old). Males may be more frequently affected. Dolichocephalic and mesocephalic breeds are at increased risk compared to brachycephalic (short-nosed) breeds, possibly because in dolichocephalic breeds more of the nasal turbinate surface is exposed to carcinogens. Living in urban areas and exposure to flea sprays, by-products of indoor kerosene/coal-burning heating units, and second hand tobacco smoke are associated with an increased risk of developing nasal neoplasms.

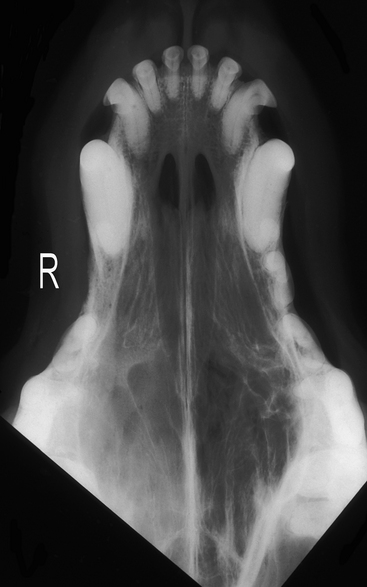

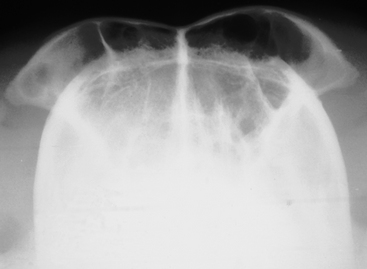

The most diagnostic skull radiographs are the open-mouth (dorsoventral or ventrodorsal intraoral) and the frontal sinus (rostrocaudal or “skyline”) views (Figs. 15-1 and 15-2). Left and right lateral oblique views are also typically evaluated. Radiographs of diagnostic quality require general anesthesia to ensure immobility.

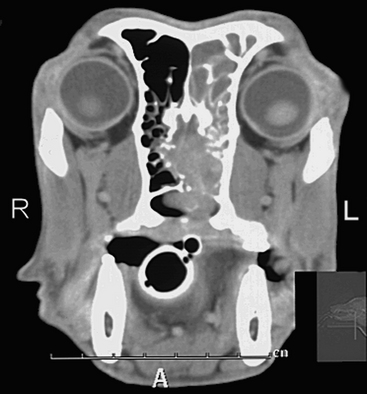

Plain radiography is an adequate screening test to rule out some causes of epistaxis or nasal discharge; however, advanced imaging is needed to assess the disease more completely. CT with and without contrast/enhancement is more accurate for determining the extent of local tumor infiltration than is plain radiography (Fig. 15-3). Furthermore, the length of survival is related to the extent of tumor involvement based on CT findings for dogs treated with radiation therapy.