Trematodes (Flukes) of Animals and Humans

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, the reader should be able to do the following:

Key Terms

Operculum

Amphistome

Schistosome

Schistosome cercarial dermatitis

Black spot

The following organisms are flukes that may parasitize domesticated and wild animals. A few species are known to parasitize humans.

Flukes of Ruminants (Cattle, Sheep, and Goats)

Parasite: Dicrocoelium dendriticum

Host: Sheep, goats, and cattle

Location of Adult: Bile duct

Intermediate Hosts: First intermediate host – Cionella lubrica, land snail; second intermediate host – Formica fusca, ant

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Forked bowel

Transmission Route: Ingestion of infected ants

Common Name: Lancet fluke

Dicrocoelium dendriticum is commonly referred to as the “lancet fluke” of sheep, goats, and cattle. This tiny, flattened, leaflike fluke is only 6 to 10 mm long and 1.5 to 2.5 mm wide (Figure 8-1) and has an oral sucker, a ventral sucker, tandem testes, and a lateral vitellaria (an accessory genital gland that secretes the yolk and shell for the fertilized ovum). These flukes are found in the fine branches of the bile duct and can produce hyperplasia of the bile duct’s glandular epithelial lining resulting in bile duct obstruction. This fluke produces brown, embryonated eggs that are 36 to 46 µm × 10 to 20 µm. The egg possesses an operculum (similar to a hinged hatch) on one pole (end) of the egg. This operculum is said to be indistinct. The first intermediate host is the land snail, Cionella lubrica, while the second intermediate host is the ant, Formica fusca. The eggs can be found on standard fecal flotation or fecal sedimentation procedures.

Parasite: Paramphistomum species and Cotylophoron species

Host: Cattle, sheep, goats, and other ruminants

Location of Adult: Rumen and reticulum

Intermediate Hosts: First intermediate host– aquatic snail; second intermediate host– none, cercariae encyst upon aquatic vegetation

Distribution: Worldwide (Paramphistomum sp.)

Derivation of Genus: Beyond a mouth on both sides (Paramphistomum sp.); ridge cup (Cotylophoron sp.), bears a cup shape

Transmission Route: Ingestion of aquatic vegetation with metacercariae

Common Name: Rumen flukes

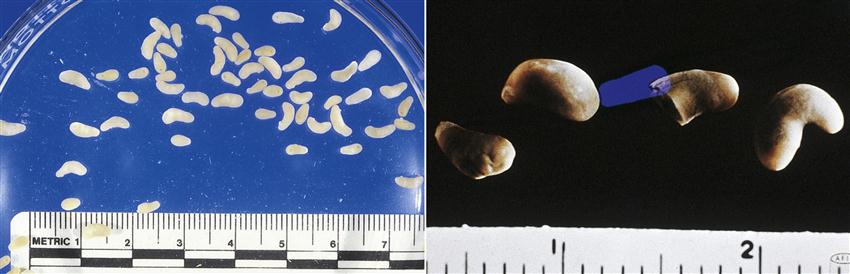

Rumen flukes comprise two genera of veterinary importance, Paramphistomum and Cotylophoron (Figure 8-2). Rumen flukes belong to a group of flukes called amphistomes (amphi means “on both sides” or “double,” and stome means “mouth”); these flukes appear to possess a “mouth” at both ends of their bodies. Amphistomes have an oral sucker (the feeding organelle, or “true mouth”) on the anterior end and a large ventral sucker (an organ of attachment) on the posterior end. The adult flukes closely resemble Kellogg’s Rice Krispies™. In the fresh state, amphistomes are light-colored to bright red and pear-shaped, approximately 5 to 13 mm × 2 to 5 mm. They attach with the oral sucker to the lining of the rumen and reticulum of cattle, sheep, goats, and many other ruminants and expose the ventral suckers (Figure 8-3). The adult flukes are nonpathogenic; the pathogenicity of these flukes lies in the migration of the juvenile forms in the small intestine. These juvenile forms are known for the ability to ingest large plugs of intestinal lining. The eggs of Paramphistomum species measure 114 to 176 µm × 73 to 100 µm; the eggs of Cotylophoron species measure 125 to 135 µm by 61 × 68 µm. The prepatent period for Paramphistomum species is 80 to 95 days.

Parasite: Fasciola hepatica

Host: Cattle, sheep, and other ruminants

Location of Adult: Bile duct

Intermediate Hosts: First intermediate host – aquatic snail; second intermediate host – none, cercariae encyst on aquatic vegetation

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Small band

Transmission Route: Ingestion of aquatic vegetation with metacercariae

Common Name: Liver fluke

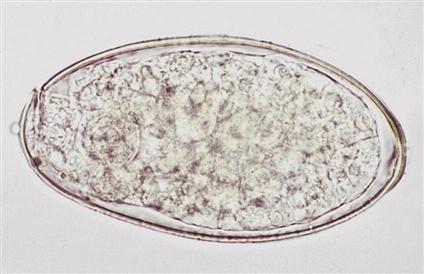

Fasciola hepatica is the liver fluke of cattle, sheep, and other ruminants. It is perhaps the most economically important fluke in veterinary medicine because it causes “liver rot,” clay pipe stem fibrosis or liver condemnation, at slaughter due to obstruction of the bile ducts. This fluke is the best-known fluke among those parasitizing food animals; parasitologists have studied F. hepatica more than any other fluke. Adult flukes are found in the bile ducts of the liver and possess a unique appearance. They are flattened and leaflike, measuring 30 × 13 mm (Figure 8-4). These liver flukes are broader in the anterior region than in the posterior region and possess an anterior cone-shaped projection that is followed by a pair of prominent, laterally directed shoulders. The internal morphology is not easily discernible due to the superimposition of a high branched ceca over highly branched testes, ova, and vitellaria. These flukes are tan to reddish brown in the fresh state; preserved specimen take on a grayish appearance. Their eggs are oval, yellow-brown, and measure 130 to 150 µm × 60 to 90 µm. Each egg will possess a distinct operculum (Figure 8-5). The eggs can be found on fecal sedimentation.

Parasite: Fascioloides magna

Host: White-tailed deer

Location of Adult: Liver parenchyma

Intermediate Host: Aquatic snail, the cercariae encysts on aquatic vegetation.

Distribution: North America, Central and Southwestern Europe

Derivation of Genus: Band shape

Transmission Route: Ingestion of vegetation with metacercaraie

Common Name: Liver fluke of wild ruminants (deer)

Fascioloides magna is also a liver fluke; however, this fluke has the white-tailed deer as its true definitive host. It may also use cattle, sheep, and pigs as incidental hosts. The adult flukes are found in the liver parenchyma and possess a unique appearance. They are large, flattened, flesh-colored, oval flukes, measuring up to 10 cm in length, 2.5 cm in width, and 4.5 mm in thickness, approximately the size of a US gold dollar (Figure 8-6). These flukes lack the anterior conelike projection of F. hepatica. The egg is operculated, up to 170 µm in length and 100 µm in width. F. magna flukes produce open cysts in the liver parenchyma of white-tailed deer. These cysts communicate with the bile ducts, allowing eggs to be passed to the external environment. Thus, eggs are often found on fecal sedimentation procedures of these infected hosts. In incidental hosts such as cattle and sheep, however, these flukes produce closed cysts in the liver parenchyma. These cysts do not communicate with the bile ducts, so the egg of F. magna cannot pass to the external environment. Incidental hosts act as “dead end” hosts; that is, they are not capable of transmitting this parasite to other animals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree