Chapter 12

Treating Sick Animals and End-of-Life Issues

- 12.1 Introduction

- 12.2 Treating Sick Animals – Modern Veterinary Medicine

- 12.3 End-of-Life: Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- 12.4 Ethical Issues Relating to Veterinary Treatment

12.1 Introduction

As we saw in Chapters 1 and 3, many people who keep animals as companions consider them to be family members, and often see them as being irreplaceable (Milligan, 2010). Owners of dogs and cats therefore, not only provide for the animals’ basic requirements (food, water, shelter), but also take care of their health and comfort. The owner’s relationship to a companion animal can become even more complex as the animal ages, or becomes ill; many owners are willing to go to great lengths and spend large sums of money caring for their animal companions, in sickness and in health.

As a result, difficult veterinary consultations may involve counselling owners to stop treatment of terminally ill animals (in contrast to previous decades, where vets more often had to discourage owners from euthanasing healthy companions). This is in part driven by advances in modern veterinary medicine making it possible to prolong the life of chronically ill or old animals, sometimes irrespective of their quality of life, or chances of recovery. The human attachment to a companion animal can be strong and highly emotionally charged, making it very difficult for some owners to be objective when it comes to making decisions about their companion’s treatment. Equally, professional, or financial, interests may motivate vets to recommend and undertake advanced investigations, or prolong treatments, even when the prognosis for the animal is poor.

Even with modern treatment advances, however, the average lifespan of companion animals remains much shorter than that of humans, with cats living around 12–16 years, and canine lifespan varying with size (average 8.5 years for a Great Dane, to 14 years for a Yorkshire Terrier). As a result, most people will experience the death of one or more of their companion animals. In some cases, the owner will actually have to take the decision to end the life of their companion animal; a uniquely stressful and at times, ethically challenging decision.

In this chapter, we begin by describing how modern veterinary medicine can extend the quality and quantity of animals’ lives, through preventative health measures such as vaccination, access to pain medication and antibiotics, and more advanced treatments such as chemotherapy, blood donation and organ transplantation. We then consider veterinary aspects of palliative care of chronically or terminally ill animals, and euthanasia. Finally, we explore a number of ethical issues that arise as a result of the availability of veterinary treatment, including when the treatment may not be in the best interests of the individual, or other animals, and the option of euthanasia for ill animals.

12.2 Treating Sick Animals – Modern Veterinary Medicine

Advances in veterinary medicine over the last decade enable many animals to be treated that would previously have suffered, died, or been euthanased. Treatment may be preventative (e.g. vaccination), curative, or palliative (relieving the symptoms, but not curing the underlying condition).

Much of general veterinary practice involves providing preventative health care for animals, including regular vaccinations, worming, dietary advice and dental care, as well as treating sick pets. Owners are encouraged to take their pets to the vet for annual vaccination, and a general health check: routine vaccination against common diseases such as canine distemper and parvovirus, and feline leukaemia, has enabled millions of vaccinated animals to live longer and healthier lives. Neutering of young animals that are not going to be bred from is, in some parts of the world, widely promoted as another aspect of responsible pet ownership (see Chapter 10). In addition, many practices provide services aimed at educating clients in responsible pet ownership, by running puppy socialisation classes and training classes (see Chapter 9) and by offering behavioural advice, and other support, such as obesity clinics (see Chapter 8).

When presented with ill animals, modern vets have access to a wide range of drugs to treat chronic diseases such as heart failure, diabetes, osteoarthritis and renal disease, improving the quality and length of life of sick animals by many years. Many drugs that were previously only available for people are now routinely used to treat animals, including powerful painkillers, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids, and antibiotics. Life-saving procedures such as blood transfusions are also now routinely performed in cats and dogs in general practice in the United States, Europe and Australasia. In some places, people typically ‘volunteer’ their pet as a donor animal, in others, colonies of dogs and cats are kept as donors in University hospitals. Commercial pet blood banks also exist. Donor animals receive regular health checks, and although the procedure is minimally invasive, the donor must be fasted, sedated, have a cannula inserted into the jugular vein in the neck, and be restrained while the blood is collected; this tends to be better tolerated by dogs than cats. In addition, there may be welfare costs involved in housing colonies of donor animals in kennels or catteries.

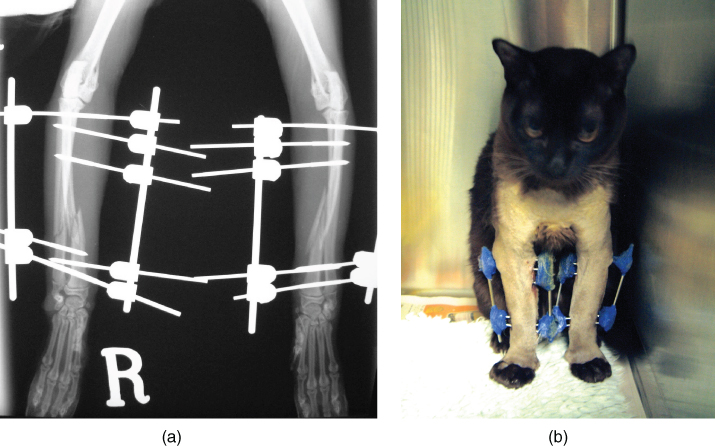

When cases are complex, or require advanced investigations or treatments, vets, like their medical colleagues, have the option to refer animals to specialists in fields such as orthopaedics, oncology and critical care. Such specialists have undergone several years of postgraduate clinical training in their chosen field. Within specialist practice, veterinary patients may undergo advanced investigations using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), previously only available for people. Many previously fatal diseases can also now be routinely treated in companions, for example, using chemotherapy and radiation to manage many types of cancer, based on protocols adapted from human medicine. Where medical treatments fail, advanced surgical treatments such as hip and elbow joint replacements, or heart valve replacements, are available for companions whose owners can afford them, in many specialist veterinary centres throughout the developed world (Figure 12.1(a) and (b)).

Figure 12.1 Advances in veterinary care mean that surgical techniques previously only available for humans are now routinely used in animals. This young Burmese cat suffered severe fractures of both front legs (a), but was comfortable and walking the following day, after having bilateral external skeletal fixators applied (b).

(Images used courtesy of Sandra Corr.)

In more extreme cases, an animal’s life may be saved when it is given an organ from another animal. In renal transplantation, a healthy kidney is surgically removed from a healthy donor animal, and implanted into a recipient animal with renal failure. The donor is often a stray animal from a rehoming shelter, and the usual policy is that the owner of the recipient animal must then adopt and care for the donor for the rest of its life, although this is difficult to enforce.

Renal transplantation is legal in many countries, but the procedure is controversial; it has mainly been performed in the United States, and to some extent in Australia. In the United Kingdom, RCVS (2013) guidance on renal transplantation is at the time of writing suspended, pending review. The first Renal Transplantation Program was started in the University of California (Davis), in 1987, and in 2004, it had the capacity to perform around 24 transplants each year, with success rates of 75–80% in cats and 40% in dogs (although ‘success’ is not defined; UC Davis, 2004). Studies have reported that up to 29% of cats receiving renal transplants die before discharge, and the remainder have median survival times of 365–613 days (Matthews & Gregory, 1997; Schmiedt et al., 2008). No studies have reported the fate of the donor cats.

12.3 End-of-Life: Palliative Care and Euthanasia

Palliative care is treatment that relieves the symptoms of a disease or condition without curing the underlying cause; examples include giving painkillers to manage cancer pain, or administering nutrition via a feeding tube to an animal that is unable to eat. Palliative care is well established in human medicine, and is a growing field in veterinary medicine, particularly in the United States (where funeral homes and memorial services are also increasingly offered for animals). Palliative care of human patients may enable them to gain a little time, for example, to spend with their children, or to survive for a significant occasion (Löfmark, Nilstun & Ågren Bolmsjö, 2007). In the case of companion animals, it is the owners who often require the extra time to come to terms with losing their pet.

With advances in both human and veterinary medicine, concern is increasingly raised over whether prolongation of life at all costs is in the best interests of the patient. As most countries do not currently permit active euthanasia or assisted suicide of people (the exceptions include the Netherlands and Switzerland), the most difficult decision in human end-of-life care usually involves the point at which transference from curative to palliative care is made (Löfmark, Nilstun & Ågren Bolmsjö, 2007). In veterinary medicine, where euthanasia of incurably ill animals is the norm, the difficult decision often involves deciding when to perform the euthanasia.

In its broadest sense, euthanasia is defined as ‘the action of inducing a gentle and easy death’ (OED, 2014), where death is intended, or at least foreseen. Here we are concerned with active euthanasia (killing) rather than passive euthanasia (letting die when one could keep alive). Normally, active euthanasia refers to killing for the benefit of the one killed, such as would be the case with very ill and dying animals. (There is some controversy about using the term to describe the painless killing of healthy but unwanted animals – see Chapter 13.) The practice of active euthanasia is perhaps the most significant difference between human and veterinary medicine, and the claim is often made, in this context, that animals are in this respect treated better than humans.

In companion animals, euthanasia is most commonly performed by administering an overdose of an anaesthetic drug intravenously into a catheter placed into a vein in the animal’s leg, which causes cardiac arrest (usually within 1 minute). Other than the catheter placement, the procedure is painless and appears to cause minimal distress to the animal. Most vets will arrange for cremation of the body, either individually (with many owners requesting return of the ashes), or as a group cremation with other deceased animals, although some owners elect to take the body home for burial (where local laws permit this) (Figure 12.2).

Figure 12.2 Euthanasia of a stray cat with severe head injuries. The cat was initially given first aid; however, the owner could not be found, and due to the severity of the injuries, the cat was euthanased the following day. An injection of Euthatal (Pentobarbital sodium) is being administered via an intravenous catheter into the cephalic vein.

(Image used courtesy of Sandra Corr.)

For some people, the decision to euthanase an animal is straightforward, either on financial, convenience, or compassionate grounds. In many cases, however, the owner’s attachment to a companion animal means that the decision to undertake euthanasia is often a difficult and protracted one (see Section 12.4.3). In some European countries, for example, Denmark, legislation requires that incurably ill animals should be euthanased if a prolonged life will lead to unnecessary suffering; and it is a legal offence for a vet not to act on such a case (Ministeriet for Fødevarer, 2014: § 20). Different ethical issues are raised by the euthanasia of healthy animals: these are considered in Chapter 13.

12.4 Ethical Issues Relating to Veterinary Treatment

As developments in veterinary medicine keep pace with human medicine, owners and vets have to make increasingly complex decisions about medical treatments. As animals cannot communicate preferences about their own treatment, they must rely on their caregivers – owners and vets – to make decisions, each of whom may have a different agenda (Yeates, 2010). One area of difference is likely to concern whether the interests of the animal, the owner, or even the veterinary surgeon, should take priority, and to what extent. Our inability to decide how, or if, a sick animal would want to be treated – or even whether an animal can form a preference – resembles the situation with people who cannot make or express informed decisions, such as the very young, the mentally impaired, or comatose patients. In such cases, the principle of ‘best interests’ is usually applied, choosing the action that is likely to produce the greatest balance of benefit over harm for the individual, with best interests described as:

being free of distressing physical symptoms, being free of excessive psychological, emotional and existential suffering, to have dignity preserved and to live in a state that is generally regarded as not worse than death.

(Berger, 2011)

Perhaps not all of these interests can straightforwardly be attributed to animals, but the underlying principles can inform decision making.

Taking ‘best interests’ as a goal also implies that the interests of the animal are paramount, and does not necessarily take into account those of the owner or other interested parties. This focus on the animal is adopted by those who favour ‘patient advocacy’, a view promoting the treatment most likely to provide the greatest benefit with least risk to the animal, irrespective of the owner’s wishes and financial constraints.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree