Fig. 3.1

Relevant features of the natural habitat have been provided for these spoonbills in the form of several nesting platforms, sticks for nesting material and an adjacent body of water (not shown) (picture: Jane Cooper)

3.2.4 Relevance of Behaviour and Time Budget in the Wild

As a matter of principle, animals should be free to display a range of natural behaviour that is appropriate for their species (Farm Animal Welfare Council, 1993; Petherick, 1997; Anonymous, 2001). Information on the behaviour of a species in the wild, such as ethograms and time budgets, is sometimes available and can provide useful guidance to help determine appropriate behaviour in captivity (Poole and Dawkins, 1999). This also applies to domesticated animals; for example, modern breeds of domestic fowl have become successfully re-established in the wild and found to display wild-type behaviour despite thousands of years of domestication (McBride et al., 1969; Andersson et al., 2001). However, it is important to remember that not all “natural” behaviours necessarily promote welfare – a bird fleeing for her life from a predator or losing a fight will almost certainly experience a level of distress. The goal should therefore be to protect animals in human care from such obviously negative experiences as far as possible, while allowing and encouraging them to perform behaviours that are likely to promote positive welfare (or reduce negative mental states) such as exercise, foraging, hiding and play (Young, 2003). It is also important to be aware of the way in which the activity of a species varies with circadian and seasonal rhythms and to give due weighting to facilitating all behaviours, not necessarily just the ones that the animals perform most frequently. As an analogy, many humans spend most of their time in the bedroom and least in the bathroom, but few people would want to live without a bathroom (Young, 2003).

3.2.5 Compatible Conspecifics

Some avian species are largely solitary, whereas many others are highly gregarious throughout their life cycles and respond poorly to solitary housing in captivity. Different species may also form flocks at certain times of day, e.g. when foraging or roosting, or times of year, such as during the breeding season (Kirkwood, 1999). The requirement of social animals for group living should be taken very seriously indeed. However, if groups are not formed, housed and maintained appropriately, individuals of even the most strongly social species can injure or kill other birds by fighting or injurious behaviour such as vent pecking (Duncan, 1999; Green et al., 2000; Anonymous, 2001). It is essential to research the social behaviour of each species when determining group size and composition with respect to sex and age. Groups must be formed at appropriate life stages, i.e. usually very early in life, kept stable, and housed in good quality environments with sufficient space (see above). Even where all of these requirements are fulfilled, there will inevitably be agonistic interactions between individuals, which will range from short, non-injurious encounters (such as a dominant bird pecking a subordinate, who then moves out of her way) to more serious fights. It is important to accept this yet ensure that the animals are protected from unacceptable levels of injury and stress as far as possible. This should be achieved by good and careful husbandry, not by singly housing birds and denying them the company of their own kind (Hawkins et al., 2001).

3.2.6 Promoting Good Health

Good health is certainly necessary for good welfare, but it is very important not to confuse health with welfare. Too much emphasis on high health standards can result in designing sterile, barren environments in the belief that this is required to reduce disease risk to an acceptable level. Animals housed in such an environment will be healthy and disease-free, yet their welfare will be poor because they are suffering from stress, fear, boredom or anxiety. It should be possible, in all areas of animal use, to strike a balance between adequate monitoring and health maintenance and providing an acceptable standard of welfare (Hawkins et al., 2001).

3.3 Considering Natural Habitat and Behaviour

When designing or evaluating accommodation for birds, it is good practice as a basic principle to first consider the type of habitat in which the species occurs. This is consistent with the assumption that welfare is good when animals are in harmony with their environment. Natural selection has resulted in animals designed to live in a particular, species-specific environment of evolutionary adaptation (EEA) and each species has evolved a number of adaptive behavioural and physiological control systems that enable it to live in such environments (Anonymous, 2001). These systems are partly autonomic but also partly under the control of cognitive and emotional systems.

It is generally accepted that animals living in an environment that contains key elements of their species-specific EEA will perform a wide range of natural behaviours, will not experience housing-related stress and will have a good standard of welfare (Anonymous, 2001). There is a good deal of easily accessible information available on the natural habitat and behaviour of birds, produced for a range of technical levels from popular publications to the scientific literature. It is also increasingly common for publications on domestic birds to include information on the behaviour and ecology of their wild ancestors.

Beliefs that domestic animals are fundamentally different to wild-type birds and fully adapted to the environment that humans have provided for them should always be critically questioned (Jensen, 2002). It is generally the case that animals are simply not able to express natural behaviour in an impoverished environment that does not provide adequate space or resources, but will readily do so as soon as they are transferred to a more appropriate environment. This has been repeatedly demonstrated in domestic fowl (McBride et al., 1969; Andersson et al., 2001) and in domestic mammals including pigs (Stolba and Wood-Gush, 1989), rabbits (M Stauffacher, personal observations) and inbred strains of laboratory mice and rats (Dudek et al., 1983; Berdoy, 2001; Berdoy, 2003). From the available evidence, it is clear that all birds should be given the benefit of the doubt and should be provided with resources that replicate or simulate important features of their EEA.

It will not always be immediately obvious what is, or is not, important to a bird, since birds and great apes (e.g. humans) inhabit very different sensory and cognitive worlds (Hawkins et al., 2001). However, some environmental features are easy to identify and verify, such as water for ducks, and consideration of the way in which species interact with their environment and use the resources within it will provide further guidance. Some examples of habitat features and behaviours to consider when reviewing the literature to inform housing design are set out below.

3.3.1 Range Sizes

Under most circumstances, an individual or group’s home range in the wild will be far larger than the accommodation that can be provided in captivity. This is a potentially serious welfare issue; for example, a positive correlation has been defined in mammalian carnivores between minimum home range size and both stereotypic behaviour and infant mortality in captivity (Clubb and Mason, 2003). It has been suggested that these behavioural and health problems are due to confinement in relatively small spaces and also to living in an environment that is not necessarily barren, but is predictable and lacks novelty. The relationship between range size in the wild and the potential for poor welfare in captivity has not been evaluated for birds, but many species range over large areas and take in and assimilate a great deal of information about their environment. Range size is thus a factor that should be borne in mind when determining space allowances for birds.

3.3.2 Locomotion

Birds move by flying, walking, running, swimming and diving. Ideal housing will allow them to perform all of the locomotory behaviours that they would do in the wild, to ensure appropriate levels of exercise and to permit a range of natural behaviours. Flight in captivity can pose particular problems in larger birds, who may have to be prevented from flying to avoid injury (see Section 3.6.5). Any restriction on the ability of birds to exercise in a species-specific way must be very strongly questioned; if such restrictions cannot be overcome then the justification for keeping the birds at all should be challenged.

3.3.3 Distances Between Individuals

Normal social behaviour for many species involves maintaining appropriate distances between individual birds (Keeling and Duncan, 1989; Channing et al., 2001). Housing that does not permit this will cause acute and chronic stress that could lead to aggression and other injurious behaviour and is also a serious welfare problem in itself. Precise information on acceptable inter-bird distances will be difficult to find or unavailable for many species, apart from those that are intensively reared such as domestic fowl. Nevertheless, it is important to take social behaviour and spacing into account when deciding on space allowances, especially if there have been problems with agonistic behaviour.

3.3.4 Trees and Other Perches

The requirement for perches for most species seems obvious, especially for passerine birds. However, perching serves different functions and the optimal nature and layout of perches in captivity needs to accommodate each of these. This is covered in more detail in Section 3.5.1.

3.3.5 Cover

Some predominantly ground-living birds, such as quail, are highly dependent on the cover and refuge provided by vegetation such as grasses and shrubs (Buchwalder and Wechsler, 1997). Species that make use of cover in this way are very likely to require some kind of natural or artificial cover in captivity and could suffer significant stress if this is not provided.

3.3.6 Water for Swimming and Bathing

The way in which a species interacts with water in the wild should be used to inform good husbandry practice. Ducks and geese are obviously wetland specialists (to varying degrees), so should not be housed without adequate water for bathing at the very least. Many other species are also motivated to bathe in water and would benefit from water baths in captivity (Hawkins et al., 2001).

3.3.7 Food and Foraging

Good nutrition is essential for health, but it is also vitally important to consider feeding habits in the wild when deciding on the presentation and nature of food, the time at which it is presented, and to suggest suitable treats (Young, 2003). Birds have relatively few taste buds but nevertheless appear to have an acute sense of taste (Welty and Baptista, 1988), so giving treats can improve welfare and encourage birds to seek human contact, if this is appropriate. Note that dietary preferences are shaped by previous experience and care is needed when introducing novel foods – the standard diet should also be available, in case birds are neophobic and reluctant to eat anything new (Association of Avian Veterinarians, 1999).

Many species spend a significant amount of time foraging and should have the opportunity to forage in captivity, for example by finding food scattered in the litter, grazing, picking seeds that have been pushed into a piece of soft fruit, or using artificial foraging devices (Burgmann, 1993; Association of Avian Veterinarians, 1999). Pecking and foraging on the ground is especially important for species that inhabit forest floors covered in litter, such as many gallinaceous birds. There is a strong case that much injurious pecking is misdirected foraging behaviour (Duncan, 1999; Anonymous, 2001; Blokhuis et al., 2001), so it is vital to provide foraging and pecking substrate for these species. It has been suggested that gentle feather pecking is part of the normal social behavioural repertoire of young chicks, since more feather pecking is directed towards unfamiliar than familiar peers and introducing unknown chicks stimulates pecking (Riedstra and Groothuis, 2002).

3.3.8 Object Manipulation

Both tool use and play occur in a number of species in the wild (Marler, 1996). Locomotory, social and object play have been observed in parrots and corvids (Skutch, 1996), so these birds will have a particular requirement for toys in captivity. Passerines such as thrushes, finches and ravens and non-passerines such as vultures are known to use tools in the wild (McFarland, 1993); tool-using species may also benefit from objects to manipulate or devices such as puzzle feeders to provide extra interest. Many other species will use such objects in captivity, so the provision of toys and other objects for manipulation should not be restricted only to those species that are known to play and use tools in the field.

3.4 Providing Appropriate Housing in Captivity

As a general principle accommodation for captive birds should be as large as possible to permit exercise, appropriate social interaction and the provision of environmental stimulation. Pens or aviaries are thus usually preferable to cages, although small passerines can be provided with an acceptable quality of life if they are housed in large, enriched cages. Space is very important but is not the only consideration; the shape, construction and siting of housing for birds also needs careful thought if it is to promote natural behaviour and good health. Many birds will benefit from being housed with outdoor access or even wholly outdoors provided that appropriate shelter is provided for them, so the feasibility of outdoor access should be fully explored wherever possible (see also Section 3.6). Environmental stimulation is fundamental to good housing for birds but is not always given the priority that it deserves; this is considered in Section 3.5.

3.4.1 Pen or Cage Construction, Including Materials and Flooring

The main requirements that need to be considered when selecting materials for the flooring, sides and roof of an aviary are preventing escape, preventing injury, providing physical comfort, achieving the required level of hygiene, providing adequate ventilation, and providing good shelter and security – both from the elements and from actual or perceived predators (Kirkwood, 1999).

3.4.2 Construction and Materials

Animal housing should generally be constructed of smooth materials with no sharp projections for hygiene and safety. Aviaries are usually constructed with some solid sides, to help birds feel secure, and some mesh sides to allow light in and permit them to see and be seen. Mesh roofs provide a view of the sky and help to keep the aviary clean by allowing rain in, but do not provide shelter from rain or intense sunlight so a solid-roofed or internal area for retreat will also be necessary (Kirkwood, 1999).

Solid sides may be constructed of wood or metal; metal is easier to clean, maintain and disinfect but is colder in winter (Inglis and Hudson, 1999). Smooth, hard materials such as metal can also be noisy, both in terms of noise reflection and sounds caused during husbandry procedures such as opening and closing doors and changing food hoppers. Careful enclosure design and husbandry may be necessary to avoid unduly stressing and disturbing the birds. If the aviary is made of wood, it is absolutely essential to ensure that it has been properly treated and will be regularly inspected so that it does not rot or permit the growth of harmful fungi, such as Aspergillus. Some species, including many Psittacines, will chew wood, so it is vital to make sure that such species have adequate wood specifically for chewing and that all preservatives are non-toxic.

Suitable grid size, thickness and materials for the mesh sides should be very carefully researched to avoid discomfort or even serious injury. Soft nylon mesh is preferable to wire mesh for roofs and walls because it is more pliant and so less likely to cause injury on impact. However, it is critical to make sure that grid size, thickness and tension are correct for the species in question to avoid entanglement of the limbs or head, which can cause serious damage and distress to birds (Kirkwood, 1999). If wire mesh is used, it should be welded rather than twisted so that sharp ends do not protrude (Inglis and Hudson, 1999).

The level of hygiene required, and the bearing that this has on the choice of materials and the nature of the birds’ housing, depends primarily on the purpose for which birds are housed. Very high levels of hygiene and exclusively indoor housing may be required for some purposes, for example veterinary practices, quarantine accommodation and scientific establishments undertaking disease studies or housing specific pathogen free (SPF) birds. In such cases it may be necessary to use specialist paints or laminates for the walls and floor and to install a sealed concrete floor with adequate drainage so that the room can be washed with a high pressure hose (Duncan, 1999). Such measures can restrict the choice of materials for housing and perches etc., but this does not ever justify housing birds in barren, boring conditions. Birds, particularly some Psittacines, produce large amounts of feather dust so their housing should be well ventilated, but never draughty. Adequate rates of air change depend on stocking densities, but in general should not fall below twelve changes per hour.

3.4.2.1 Flooring

Birds should be housed on solid floors, with adequate drainage and appropriate litter if necessary (Hawkins et al., 2001). Suitable substrates vary according to the species being housed, so it will be necessary to research what the typical substrates are that are used by that species in the wild, and how and why the animal uses it. This is especially important for species that forage on the ground (Young, 2003). Sandpaper cage liners are widely available but should not be used for any species as they abrade the feet and may be ingested for the grit after they have been contaminated with faeces (Coles, 1991). Rough concrete floors without any other substrate are especially likely to cause foot trauma and infections, such as bumblefoot (Forbes and Richardson, 1996). Chipped bark, white wood shavings, wood chips or sand are suitable for most Galliformes; gravel over a concrete base for many species including Psittacines, Corvids and birds of prey; and absorbent paper, regularly changed, in indoor aviaries housing small Passerines such as tits (Hawkins et al., 2001).

Some species have highly specialised flooring requirements, and the wrong type of flooring can cause serious welfare problems. For example, in sea birds hard flooring can cause foot lesions, feather damage, pressure sores and staphylococcal infections. Flooring substrate for seabirds should be textured or uneven so as to spread the birds’ weight over the weight-bearing surface of the lower limb. Suitable materials are pea gravel, textured rubber or plastic matting, clay, cat litter or swimming pool “anti-fatigue” matting (Robinson, 2000). Similar materials are suitable for waterfowl, who can also be housed on plastic artificial turf, smooth rubber matting or deep pile rubber car mats (Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, 1993) that are comfortable and easy to clean. It may be worth trying materials such as these for other species if flooring causes foot or leg problems. Within outdoor enclosures, flooring may be grass, gravel or concrete, depending on the requirements of the species and the purpose for which the birds are kept. For example, concrete floors may be necessary for faecal collection for scientific or veterinary reasons (Inglis and Hudson, 1999), but frequent and regular foot monitoring will be required.

Birds are sometimes housed on metal or plastic grid floors, ostensibly for improved hygiene, ease of cleaning or the prevention of foot problems. However, grid flooring does not promote natural behaviour (such as foraging, see Fig. 3.2) or good welfare and so it should be avoided wherever possible.

Fig. 3.2

Pigeon pen with various enrichments including good foraging (picture: Anita Conte)

It is sometimes asserted that birds’ welfare is not impaired on grid floors, but there is no scientific basis for this. Birds can certainly exist, grow and breed when housed on grid flooring but this does not mean that their welfare is good. Domestic fowl have been demonstrated to have a strong preference for solid flooring (Farm Animal Welfare Council, 1997), and the consensus is that animals’ welfare will be impaired if they are not provided with resources that they strongly prefer. Although little research has been done to evaluate this in other birds, mammals, such as the laboratory rat, also prefer and will work hard to gain access to solid rather than grid floors (e.g. Manser et al., 1996; Krohn et al., 2003). Birds should therefore be given the benefit of the doubt and housed on solid floors; this is especially important for those that spend a significant amount of time walking, such as gallinaceous species. Suitable substrate will not only to help avoid foot lesions but also encourages foraging behaviour (see Section 3.5).

It is undoubtedly true that faeces will fall through grid floors so that they are less likely to be ingested or stick to the feet. However, regular cleaning and replacement of soiled litter will achieve the same effect while allowing birds the physical comfort of a solid floor and the ability to move and interact with other birds normally (Hawkins et al., 2001). Solid floors with litter will also require the expense of providing litter and the extra human resources to clean out cages more frequently and thoroughly, which may be the real (economic) objection to changing from grid floors. With respect to foot injury, birds are prone to foot problems such as overgrown claws, faecal accumulation and foot lesions on any type of flooring. Good husbandry and frequent monitoring of birds’ feet is therefore always necessary, regardless of floor type.

There are some cases in which birds cannot be kept on solid floors, e.g. when it is necessary to collect faecal output for scientific purposes. In such cases, it is good practice to provide birds with a solid resting area (e.g. occupying a third of the floor space). Faecal collection can be maximised by ensuring that perches are sited above grid areas (Hawkins et al., 2001).

3.4.2.2 Security and Shelter

There are two aspects to security; (i) how physically secure the birds’ housing actually is, and (ii) how secure the birds feel, according to the way in which they interpret their environment. Most birds are highly mobile and adept at escaping, and attempts to catch flying birds can cause stress or injury if carried out by people who have not been properly trained or do not have the right equipment. Bird housing therefore needs to be very secure to prevent escapes and also, in the case of outdoor housing, to prevent predators from gaining access. A double-door system is highly advisable for large pens and aviaries housing flying birds. All bird housing, whether indoor or outdoor, should be regularly and frequently inspected to ensure that there are no possible escape routes (Kirkwood, 1999). All outdoor enclosures should be supplied with appropriate shelter to make the birds feel safer and to protect them from adverse weather. In general, aviaries should be sited so as to protect the birds from prevailing winds, but the orientation of the enclosures will also depend on the species. For example, in northern temperate climates it is advisable to have a southwest exposure for aviaries housing tropical pigeons, but northeast for ptarmigan (ILAR, 1977).

The appropriate number of solid and mesh sides in each case will reflect a compromise between the birds’ needs to feel that they have a safe refuge and that they are in an established social group. Birds are likely to feel safer, more secure and less stressed if their cage or pen has just one rather than all mesh sides, but this will restrict their ability to see into adjacent pens containing conspecifics if pens are located in a row and/or opposite one another. In practice, judgements on enclosure materials and layout will depend on factors such as the behaviour of the species, previous experience of individuals, number of birds and species housed and so on. Many birds spend much of their time above ground level (except for terrestrial species such as quail) so housing at ground level should be avoided for such species (Coles, 1991). However birds’ accommodation is laid out, it is important to ensure that caretakers are able to see inside the housing and that birds are still exposed to, and therefore able to habituate to, humans. This is especially important where frequent intervention and observation is required, for example if birds are under veterinary care or are the subject of scientific procedures.

Aviaries should be screened from paths and from each other, using hedges, fencing or close-weave netting (Inglis and Hudson, 1999). This is especially important if it is not possible to avoid housing predators and prey species close to one another. However, there is an obvious conflict of interests where birds are required to be seen by the public, for example in zoos, “pet” shops, bird shows (in particular) and some rehabilitation centres, since being closely viewed by unknown or even familiar humans is likely to cause stress (Carlstead and Shepherdson, 2000; Young, 2003). Careful thought should therefore be given to the way in which humans are able to approach aviaries (Young, 2003). It is good practice to ensure that they can only be approached from one side and to place the birds’ shelter in such a way as to give them a clear “safe area” if they become afraid (see Fig. 3.3) (Inglis and Hudson, 1999; Carlstead and Shepherdson, 2000). If it is necessary to enter the enclosure regularly to clean and maintain it, sticking to a regular, defined “service route” that avoids nesting and roosting areas will reduce stress to the birds (ILAR, 1977). For comprehensive guidance on appropriate barrier design and materials see Young (2003).

Fig. 3.3

Large flight pen with good natural screening in the form of a hedge together with screened doors which protect the birds from external disturbance (picture: Jane Cooper)

3.4.3 Space Requirements

In common with all other animals, birds need enough space to perform a wide range of behaviour including appropriate social interactions and exercise. Good bird housing should include sufficient space for environmental enrichment and there should be no signs of social stress caused by insufficient space and/or overstocking. Few studies have evaluated appropriate space allowances for captive birds, and so judgements on enclosure sizes and stocking density tend to be based on what is perceived to be best (or acceptable) practice. Views on what constitutes best practice, and which factors need to be taken into account to determine this, can differ considerably. To be in a strong position when advising on bird housing, it is essential to set out clearly what you would expect the animals to have and be able to do, then use this as a basis for determining whether the current or proposed husbandry will allow adequate space. For more guidance on this, see the resources listed in Section 3.8 of this chapter.

If it is not possible for birds to be housed in aviaries or pens that are large enough to meet their needs, then the next best option is to allow birds regular access to a flying area (Hawkins et al., 2001; Young, 2003). This could be a room in a bird keeper’s home, an aviary (which may be portable) or a designated room equipped with perches, dust- and water baths, foraging materials and toys as appropriate to enable birds to exercise and play (Huber, 1994; Nepote, 1999). It is important to remember that aviaries or flight rooms will need to be long enough for controlled flight that will also enable birds to exercise appropriately; if space is limited then long, narrow flights are preferable to wider, shorter enclosures. Birds should only be introduced to flight rooms in established groups and will require monitoring to ensure that subordinates are not bullied (Nepote, 1999). Training birds to return to the hand or to a catching box containing a treat will reduce stress when they need to be returned to their holding accommodation (Hawkins et al., 2001). This has successfully been achieved with pigeons in a laboratory setting (Huber, 1994), so deserves consideration with other species and contexts, including owners’ homes.

Suggestions that bird accommodation is improved by allowing more space or reducing stocking density may be met with the response that the housing meets with relevant legislation, e.g. relating to farming or the use of animals in scientific procedures (Home Office, 1989). It is important for inspectors or others concerned with promoting good welfare to challenge this, since legal minimum space allowances and maximum stocking densities are not best practice, but are minimum standards and often disproportionately weighted towards the requirements of industry rather than the needs of the birds. As such, they often lag behind new knowledge about animal behaviour and welfare needs.

Minimum standards may be based on the size or body mass of the birds (Home Office, 1989), or on the space that individuals require to perform “comfort” movements, but this does not allow for exercise or social interaction and should not be used to calculate space allowances for long term living accommodation. For example, the space required for domestic fowl to perform comfort movements is 2,000–2,500 cm2 (0.2–0.25 m2) (Dawkins and Hardie, 1989), yet individuals will walk up to 2.5 km per day and fly to and from elevated places if they have the opportunity to do so (Keppler and Fölsch, 2000). Domestic fowl perceive the area that they require to flap their wings as larger than it actually is (Bradshaw and Bubier, 1991), and it is reasonable to assume that the same will be true of other species as a behavioural adaptation to avoid feather and wing damage. Laying hens are motivated to walk and explore their surroundings during the early stages of pre-laying behaviour and develop stereotypic pacing if they do not have sufficient space (Duncan and Wood-Gush, 1972). Fowl also maintain social distances between one another depending on social attraction and repulsion forces (Keeling and Duncan, 1989), which have been found to be 2 m or more in feral domesticated birds (McBride et al., 1969). Taking all of this into account, an area of 0.2–0.25 m2 per individual is clearly not adequate to permit a range of behaviours, especially exercise and social interaction.

In the case of farmed birds, minimum legal space allowances (if they exist) are likely to be inadequate and cause poor welfare, so it is good practice to use voluntary, higher welfare standards as guidance. Codes of practice for laboratory birds (again, if they exist) are likely to include higher space allowances than for farmed birds, but may also fail to fulfil the birds’ basic needs. This means that the welfare of birds housed according to legal standards is not necessarily good. To express this another way, complying with a standard does not absolve those housing birds from paying due consideration to animal welfare and providing more, better quality space if necessary.

One would expect companion birds to be provided with a good quality and quantity of space, both to enable their keepers to enjoy watching a broad range of bird behaviour and also because they are valued as individuals more than birds used in other contexts. However, due to lack of awareness about birds’ behavioural needs, unwillingness to accept that a loved companion may be suffering (Young, 2003) and the continued availability of small, cheap cages, companion birds may also have to endure inadequate housing. For example, one leading “pet” store’s website says that cages should measure at least 2–3 times a bird’s wing span by 3 times a bird’s length from head to tail tip. For a budgerigar, this works out at approximately 0.17–0.37 m3 (50–75 × 50–75 × 66 cm). However, it is possible to order from the same website a cage that is just 0.027 m3 (30 × 23 × 39 cm); an order of magnitude smaller. This is not sufficient to permit an appropriate range of behaviours or to supply adequate enrichment, so it is important to encourage people who keep birds in such small cages to buy bigger ones and/or to allow the birds free flight in the home (preferably both).

3.4.4 Group Size and Composition

Ideally, most social species should be housed in stable, compatible groups, or pairs at least. To minimise the risk of aggression, groups or pairs should be formed at an appropriate age, usually very early in life, and then kept as stable as possible (Hawkins et al., 2001). A good quality, interesting environment is also imperative and this is addressed in the next section of this chapter. Where birds are to be housed in groups of more than two, it is good practice to research the optimal group size and composition for the species in the wild and see whether this can be replicated in captivity.1 It is not possible to give general guidance when dealing with such a large number of species, so the rest of this section will set out some of the issues that need to be researched and considered.

Some species are especially gregarious and live in large flocks, such as species of waterfowl and many small passerines. Living in flocks confers two main benefits: a reduced individual risk of predation and enhanced location and exploitation of food. The drive to be surrounded by a large number of other birds is therefore extremely powerful and the distress experienced by individuals of such species on separation is likely to be correspondingly strong. Some species are also highly sensitive to kin relationships within flocks (Marler, 1996), especially geese who form long-term, stable family groups (Ely, 1993; Choudhury and Black, 1994).

However, territoriality during breeding seasons can lead to aggression within even stable groups. For example, male waterfowl will defend females against other males and lone males may also forcibly copulate females, which can result in injury and death. Female geese will defend their feeding resources and some geese drive other families away while rearing goslings (Owen and Black, 1990). Space allowances can be set up to take these types of seasonal behaviour change into account, by ensuring that sufficient space, resources and refuges are all available before the breeding season occurs. This will require research and consultation with other keepers of the species before any birds are acquired.

It is also necessary to check for each species whether it is most appropriate to house birds in large groups, as some should be kept in single pairs only (Forbes and Richardson, 1996). As a general rule, however, the amount of time during which any individual of a social species will be left alone should be kept to an absolute minimum. Singly housing strongly gregarious birds such as Psittacines in the belief that this will facilitate talking is not acceptable on ethical or welfare grounds, since pair housing parrots increases the birds’ behavioural repertoire and improves their welfare (Meehan et al., 2003). In the case of laboratory birds, it may be necessary to provide birds undergoing experiments with a visible companion (Stephenson, 1994), so that the minimum group size will be three (then two birds will be left in the holding accommodation while the other one is undergoing procedures).

The type of hierarchy that occurs in the species in the wild is also of key importance. Some gallinaceous birds such as the domestic fowl, quail and turkey form stable hierarchies under certain conditions and may be highly resistant and aggressive towards intruders (Duncan, 1999; Mills et al., 1999). The composition of groups of gallinaceous birds generally needs to be given careful thought and should usually comprise either one or a few males with a larger number of females, or single-sex groups, in captivity. Other species are more loosely organised; for example adult starlings are generally dominant over juveniles, and males over females, but there is no strong social structure and birds can be housed in large, mixed-sex groups (Feare, 1984).

The nature of social hierarchies also determines how easy it will be to introduce new birds into an established group. For particularly aggressive species, it may be necessary to begin acclimatising birds to one another by initially allowing birds to see and hear one each other through double-mesh walls only. Individuals of species with weaker hierarchies such as starlings can usually be introduced relatively easily provided that sufficient space and a good quality environment, including plenty of perches if appropriate, is provided (Hawkins et al., 2001). New birds can also be introduced into an existing budgerigar colony with few problems, which reflects the lack of a strong hierarchy in wild flocks (Wyndam, 1980), yet other Psittacines require a far more gradual introduction. Again, research and consultation is essential before adding new birds to a group of any species, to help prevent and overcome problems with aggression.

Birds are sometimes housed in mixed-species flocks, often in zoos or wildlife parks, and this practice should be critically considered on a case-by-case basis. Mixed flocks can occur in the wild, e.g. zebra finches may be found flocking with other small passerines (Zann, 1996), but housing some species in mixed flocks in captivity is not recommended; for example Amazon parrots should be housed in single species groups to prevent stress and aggression. Some Psittacines may even become stressed if they can see or hear other species in adjacent aviaries (Pilgrim and Perry, 1995). As a general guide, decisions regarding mixing species should be made on the basis of the behaviour of both species in the wild; any available evidence that the species can be housed in captivity without causing stress, undue competition or behavioural problems; and the reason for wishing to house the species together. If this is primarily economic and there is any probability that either species will suffer as a result, each species should be housed separately or not at all.

Some people resist group housing individuals of the same species, on the grounds that single housing is necessary to prevent aggression, which is probably the most common reason given for singly housing social animals. Birds must, of course, be protected from injury and suffering, but it is not acceptable to rely in the long term upon single housing of social animals or upon mutilations such as beak trimming, rather than reviewing and improving animal husbandry (see Section 3.6) (Hawkins et al., 2001). It is important to encourage bird keepers to review husbandry practices so that they can attempt group housing and to provide them with any support that they may need within their facility. There may also be a perception that inspectors responsible for monitoring the health and welfare of the birds (e.g. Home Office Inspectors in the United Kingdom) would penalise the keeper if any animals were injured in the course of an attempt to initiate group housing. Such beliefs are often unfounded and the issue can be resolved by encouraging better communication between the bird keeper and inspectors.

3.5 A Stimulating Environment

Providing a stimulating environment for birds is of paramount importance. Thoughtfully provided environmental enrichment allows birds to perform a range of natural or otherwise desirable behaviours, encourages exercise, facilitates appropriate social interactions and can also divert birds’ attention from any pain that they may be experiencing as a result of pathologies or veterinary or scientific procedures (Gentle and Corr, 1995; Gentle and Tilston, 1999). It should be unthinkable to house birds without adequate and appropriate stimulation, yet this still occurs for birds housed in all contexts, even “pet” birds whose keepers believe that they love their birds and care for them well (Young, 2003).

Ideally, birds should be provided with enrichment from hatch; both for their welfare and to ensure that they are habituated to items and know how to use them. If birds reared in an impoverished environment are suddenly presented with a novel item, they may be neophobic or simply not understand its relevance immediately. In such cases, new items should be sited in less used parts of the enclosure, away from feeding, drinking, resting and sleeping sites (Young, 2003). It is also very important to ensure that care staff do not become disillusioned and remove the enrichment before the animals have had a chance to habituate to it and use it. Several days may elapse before the birds begin to approach a new resource, but they may go on to obtain significant benefit from it in the long term (they may also use it most when no human observers are present). Encouraging care staff to keep an “enrichment diary” helps to maintain their interest and persevere with the enrichment programme (Young, 2003). As many birds are capable of “social” learning, i.e. learning by watching the activities of others (Sherry and Galef, 1990; Fritz and Kotrschal, 1999; Nicol and Pope, 1999), it may also help if they can see conspecifics using the resource. Even laying hens who have been housed in commercial batteries will eventually use enrichment items and display natural behaviours if they are re-homed to a more appropriate environment (Dawkins, 1993).

Besides providing birds with an interesting environment, emphasis should also be on allowing them an element of choice and control, for example by including areas for different activities such as dust bathing, water bathing, perching and play. Locating desirable resources as far apart as possible is a good way of encouraging exercise (Young, 2003). All of this will obviously require sufficient space to accommodate enrichment items in such a way as to permit effective monitoring of the birds and to allow them to be caught when necessary with the minimum of disruption.

It is very important to make sure that enrichment is relevant and appropriate to the species and will genuinely benefit the birds. Environmental enrichment is sometimes not provided because people do not know what birds really need or are worried that it may cause welfare problems, for example by increasing aggression. Having identified these concerns, the crucial next step is to address them by researching suitable enrichment and suitably testing it in situ. Sufficient resources should be provided for all the birds to be able to use them at once, since many birds synchronise their actions and the sight of an individual performing an activity such as dustbathing will frequently induce others to join in. Guidance on suitable resources and how to test them can be obtained from responsible captive bird societies, organisations such as the Shape of Enrichment, animal welfare organisations and the scientific literature (see Section 3.8). Examples of suitable enrichment for birds are listed below.

3.5.1 Perches

The ability to perch is critically important for good welfare in many species, including all Passerines (or “perching” birds) who have feet that are anatomically adapted to close around tree branches. Perches can be essential for providing feelings of security, maintaining stable hierarchies and allowing subordinate birds to escape (Keeling, 1997; Cordiner and Savory, 2001; Newberry et al., 2001). They also provide valuable exercise for the feet and legs, which helps to maintain bone strength, and facilitate short or long flights. Perches that are attached to the aviary at one end only, with a spring to enable them to bounce slightly when the bird alights, provide additional exercise and perches of a variety of different diameters will help to exercise the feet (Association of Avian Veterinarians, 1999). Natural branches (from pesticide-free and non-toxic trees such as northern hardwoods, citrus, eucalyptus or Australian pine) are the preferred materials for perches (Coles, 1991) and can be regularly replaced when soiled or gnawed. If this is not possible for practical or hygiene reasons, wooden dowelling or (less preferably) plastic perches are suitable alternatives. Note that perches should not be covered with sandpaper tubes, as these cause foot excoriation and infection and do not trim the claws effectively (Coles, 1991; Association of Avian Veterinarians, 1999).

If birds are to obtain maximum benefit from perches, it is essential to research the optimum shape and positioning for each species. It is not possible to generalise within avian orders; for example within the Galliformes domestic fowl require perches that are flattened on the top surface to prevent keel deformation (Duncan et al., 1992) but quail do not appear to require perches at all (Schmid and Wechsler, 1997). It is also important to consider why each species perches, at what time of day and for what purpose, to ensure that this very important need is properly met.

Jungle and feral domestic fowl roost at night to avoid predation and also arrange themselves on perches according to the group’s dominance hierarchy, so domestic fowl need perches sited at different heights, long enough to prevent conflict and available to them all the time, but especially at dusk. Many raptors rest on structures such as tree stumps and fence posts while manipulating and eating prey, so require a post with a flattened top (Hawkins et al., 2001). Some small passerines use tree branches to approach the ground gradually when preparing to feed, so will benefit from perches of varying diameters at a range of heights (Coles, 1991).

Ensuring that perches are placed at either end of the cage or aviary will maximise the possible distance that birds can fly (Association of Avian Veterinarians, 1999). Psittacines spend much of their time climbing in the wild so the perch layout should facilitate this (mesh walls with a suitable grid size and tension are also good for climbing). Swings may benefit some species by encouraging additional exercise and play, although some birds apparently prefer fixed perches. Swings are commercially available or can be constructed from dowelling, branches, plastic or metal.

Although perches should be placed primarily to address the birds’ needs, it is also important to remember that droppings will accumulate beneath perches so they should never be placed above food or water dishes (or other perches where possible). Care should also be taken that the birds’ tails cannot contaminate food or water or become abraded on the floor of the cage. In species that are liable to feather peck, perches should not be sited so that birds on the floor or on lower perches can reach the feathers of birds perched above them.

3.5.2 Foraging Substrate and Devices

Birds spend a significant proportion, sometimes the majority, of their time foraging in the wild (Paulus, 1988; Fölsch et al., 2002). Captive birds have been shown to choose to forage and work for food even when additional food is freely available (Duncan and Hughes, 1972), and this phenomenon of “contrafreeloading” is believed to reflect a motivation to gather information about the environment in case the food supply should become restricted (Inglis et al., 1997). The importance of increasing foraging time in captivity to improve welfare and reduce stereotypic behaviour is increasingly recognised for all animals, including birds (Coulton et al., 1997; Field, 1998). It is therefore good practice to enable birds to forage for at least part of the day, rather than feeding from one bowl or hopper all of the time.

Foraging can be encouraged in ground-feeding species by simply scattering part of the regular diet or additional items such as seeds, grains or mealworms into a foraging substrate, such as wood shavings, sand or turf (Gill, 1994; Gill et al., 1995; Nicol, 1995). This is easy to do and regular cleaning and removal of soiled food will avoid disease. The foraging substrate can be placed in large, shallow trays that can be taken out for cleaning and removing soiled food. Some species, e.g. Corvids, enjoy foraging for invertebrates such as mealworms in deep boxes filled with bark chippings. For others, food items such as sprays of Panicum millet or rings of dried apple on a string can be attached to the enclosure walls. Shelled nuts, pine cones or other foods that require manipulation should also be supplied wherever appropriate for the species. For grazing species such as geese, whole vegetables including lettuce, celery and cabbage can be fixed to the ground or suspended at bird head height to increase foraging time.

Diving and dabbling birds should be encouraged to feed underwater at appropriate depths, to encourage natural behaviour and for exercise (Kear, 1976). At least part of the birds’ diet can be thrown on the water to encourage diving (birds can be weighed regularly to ensure that they are getting enough to eat and food residues can be siphoned out of the pond) (Hawkins, 1998). Plants such as duck weed (Lemna spp.) and grains can be supplied on or in water for herbivores and omnivores. For omnivores and carnivores, suitable foods include diving duck food from specialist suppliers, small fish such as sprats or sand-eels and dried food for carnivorous mammals (this is usually available in floating or sinking form and can be fed to divers and dabblers respectively) (Hawkins et al., 2001).

Slow-release PVC feeders, floating rafts filled with fish (Sandos, 1998), or traffic cones suspended upside down and filled with fish that can be removed one at a time (Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, 1999) can also be used to prolong foraging time for aquatic carnivores (Fig. 3.4). Note that live vertebrate prey should never be given to any carnivore, as this will inevitably cause suffering to the prey animal and may result in injury to the predator if the prey defends him/herself. There are a number of suppliers of humanely killed animals such as chicks and rodents and so feeding live prey is not necessary; the practice may also contravene animal welfare legislation under some circumstances.

Fig. 3.4

A penguin pulling a fish from an underwater feeding device (an inverted traffic cone) (picture: Universities Federation For Animal Welfare)

Puzzle feeders are an excellent way of providing interest and extending foraging time (Coulton et al., 1997; Bauck, 1998). In their simplest form, these consist of fruit, wood blocks, logs or plastic pipe with holes drilled in them so that pieces of food can be pushed into the holes (Fig. 3.5) (Mendoza, 1996). These are suitable for most species, for example plastic pipe with mealworms for sea birds (Neistadt and Alia, 1994), wood with fruit and vegetables for Psittacines and finches, fruit with seeds for Psittacines (Hawkins et al., 2001). More complex feeders that require birds to perform a task to gain access to food should be provided for those species that are capable of using them, such as Psittacines, Corvids and tits. Examples are feeder balls, which must be turned around to release the food, or devices that require birds (e.g. tits) to pull levers, open doors or pull strings (Fig. 3.6). Pots with lids are also suitable, e.g. film canisters filled with mealworms or tubs filled with fat and covered with tin foil (N. Clayton, personal communication). Another option is to suspend items such as a piece of fruit or corn on the cob from a string tied to a perch, so that the bird must learn to pull up and secure the string.

Fig. 3.5

A puzzle feeder consisting of a wooden stump with holes into which food can be hidden (picture: Jane Cooper)

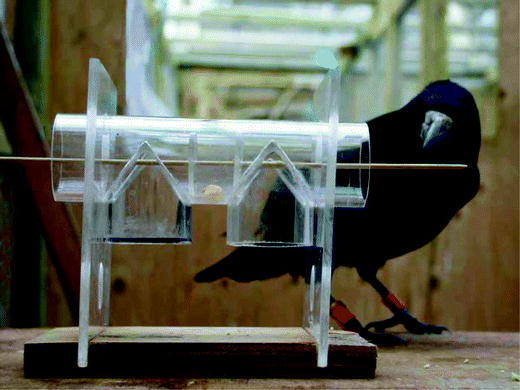

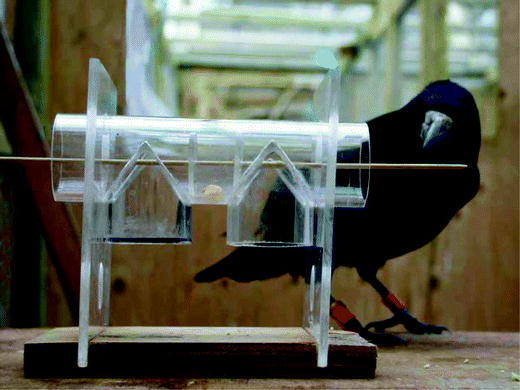

Fig. 3.6

A puzzle feeder which the bird has to manipulate in order to get a small food reward (picture: Amanda Seed)

Another important aspect of foraging behaviour in some species, especially in crows, nuthatches and tits, is the practice of caching, or storing, food to provide a reserve when it is less abundant. Any species that caches food should be fed a diet containing elements that are suitable for caching and provided with appropriate places to cache them in the ground or in crevices. These could be natural, e.g. rotten tree stumps or soil, or artificial, e.g. sections of log with holes drilled into them, or cat litter trays filled with sand or wood chippings. Caching perches can be constructed for birds such as tits and nuthatches using blocks of wood with “pockets” made from sections of inner tube (N. Clayton, personal communication).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree