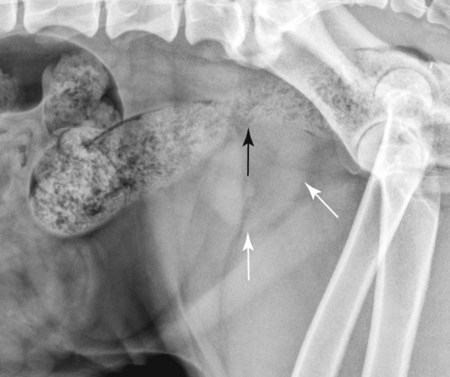

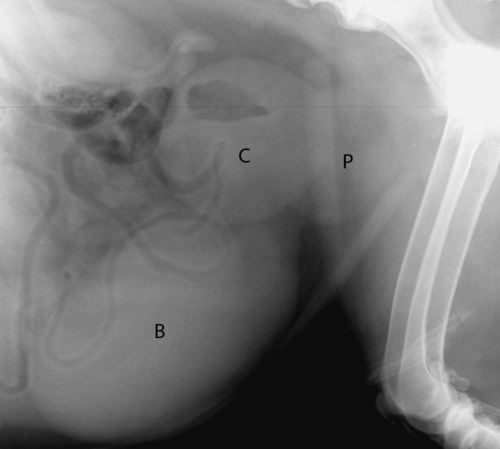

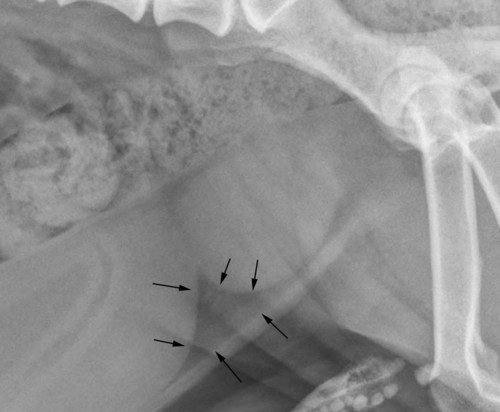

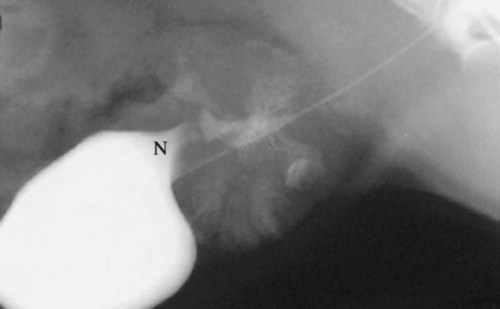

The normal prostate gland surrounds the most proximal aspect of the urethra and lies ventral to the rectum and caudal to the urinary bladder, typically within the pelvic canal. In most dogs, especially neutered dogs, the normal prostate gland is not visible radiographically. With slight enlargement, whether normal or abnormal, the prostate gland is recognized radiographically by its round shape and soft tissue opacity and by the relation of the gland to the organs around it. Inability to see the normal prostate gland is influenced by the fact that it is usually in direct contact with the rectum, resulting in the dorsal border of the gland being effaced, especially if the rectum contains feces. A full rectum may also obscure the prostate gland on the ventrodorsal view. Also, if the shape or position of the prostate gland is altered, the gland may not be recognizable other than as a nondescript opacity between the bladder, rectum, and pelvis.1 Intrinsic disease of the prostate gland usually results in enlargement. Enlargement may also occur in response to extraprostatic influences, such as an androgen-producing testicular tumor and orchitis.2 Because of the close functional association of the prostate gland and testes, any animal with prostatic disease should also be examined, preferably ultrasonographically, for testicular disease. The most common prostatic abnormality is benign prostatic hypertrophy, in which the prostate gland enlarges as a result of increased volume in the intercellular and ductal spaces rather than from increased intracellular volume or cell number. Thus once hypertrophy reaches a certain point, development of dilated cystic spaces and ducts is inevitable. Solid and cystic hypertrophy are therefore different stages of the same disease, with the latter being the advanced form.2,3 The size of the cystic spaces varies from microscopic to large; these spaces may become so large that they distort the shape of the entire gland. A cystic prostate gland may have cysts of many different sizes. Large cystic spaces predispose the gland to infection. Another common cause of prostatic enlargement is prostatitis, which is usually bacterial.4 The infection may arise within the prostate gland, or it may extend from other sources, such as the bladder or testicles.5 Because many antibiotics do not penetrate the prostate gland readily, the gland may also be a reservoir for reinfection or extension to other organs.6,7 A normal prostate gland is more resistant to infection than is a hypertrophied gland with many secretion-filled cystic spaces. The inflammation may vary from a mild transient process that causes minimal or no clinical signs to a fulminating hemorrhagic process that destroys the entire gland rapidly.8 The latter may result in rupture of the capsule with secondary peritonitis.7 Chronic, recurrent prostatitis may result in a scarred, fibrotic gland that is smaller than normal. Chronic scarring may result in stricture of the urethra.9 Such a stricture is difficult to recognize radiographically unless a urethrogram is performed. A prostatic abscess may form as a result of prostatitis or primary cystic disease. As with cyst formation, abscesses may be small or large. Large abscesses distort the shape of the prostate gland and may eventually rupture, causing peritonitis. As previously stated, cysts form in advanced benign hypertrophy and are usually contained within the gland. However, cysts occasionally become so large that the shape of the gland is distorted and the predominant opacity seen on the radiograph is caused by the large cyst. Such large cysts are also referred to as paraprostatic cysts because they are no longer confined within the gland. These cysts are usually sterile but may become infected.10 Cysts occasionally result from neoplasia.11 Formation of functional neoplastic secretory cells without an accompanying ductal system results in a cystic structure lined with neoplastic epithelium. Osteocollagenous retention cysts are rare and of unknown origin, but they do not appear to be the direct result of cystic hypertrophy.12 A rare form of cyst, which is truly paraprostatic, is cystic enlargement of the müllerian ducts, called uterus masculinus.13 Enlargement of the müllerian ducts results in a bilateral tubular mass that resembles uterine enlargement. The prostate gland itself may or may not be enlarged and usually is not distinguishable as a separate opacity.9 Prostatic adenocarcinoma is relatively uncommon; however, the incidence in intact and neutered males is similar.14,15 Prostatic adenocarcinoma is often advanced at presentation with metastasis to regional lymph nodes, the pelvis, and distant sites such as the liver and lungs.16–18 The gland is massively enlarged by the tumor in some dogs, and in others the degree of enlargement is minimal. Small in situ prostatic carcinomas are unusual but do occur; they are usually discovered as a result of metastasis rather than from their local effects. Prostatic neoplasms are often secondarily infected or necrotic, and affected dogs may therefore have clinical signs of prostatitis. These tumors are difficult to diagnose, unless signs of metastasis are present, because of the tendency of infection to overshadow neoplasia.19–21 The clinical signs of prostate gland disease are usually referable to either urinary or rectal problems. Stranguria, hematuria, and pyuria are seen commonly.5,8,10,13 Complete urethral obstruction is possible but unusual.3,22 Another common symptom with prostatic disease is dyschezia with small or ribbonlike stools.8,22 As the enlarging prostate gland displaces the colon and/or rectum dorsally (Fig. 41-1), the bowel can be compressed against the sacrum and pelvis, resulting in narrowing. Severe rectal compression by the prostate gland may cause clinical and radiographic signs of constipation or obstipation. A less common sign of prostate gland disease is a pelvic limb gait abnormality. The animal may refuse to climb stairs and jump. Owners often believe the animal has developed osteoarthritis, but such animals may have severe, active septic prostatitis.5,8 The pain caused by the prostatic infection is exacerbated by walking, climbing, and jumping. Both pelvic limbs are usually affected. These animals are also usually sensitive to palpation of the caudal abdomen. Gait abnormalities are seen rarely in uncomplicated benign prostatic hypertrophy. All common prostate gland diseases cause enlargement. The enlargement may be symmetric (diffuse in origin), asymmetric (focal in origin), or a combination of the two. Prostatic symmetry is usually judged by the shape of the prostate gland and the relative mass of the prostate gland with respect to the neck of the bladder. Hypertrophy and prostatitis are examples that usually cause symmetric enlargement (see Fig. 41-1), whereas neoplasia and cysts are examples that usually cause asymmetric enlargement (Fig. 41-2). Radiographic identification of the prostate gland depends on the presence of surrounding fat; the gland may not be seen in very thin animals or those with fluid in the area of the neck of the bladder. A reliable sign of prostatomegaly is a triangular region of fat between the bladder, prostate gland, and ventral abdominal wall (Fig. 41-3). Identification of prostatomegaly hinges on identification of a soft tissue mass in the caudal aspect of the abdomen and on the relation of that mass to surrounding structures, principally the bladder and colon. Prostatomegaly typically displaces the bladder cranially (see Fig. 41-1). If prostatomegaly is uniform, bladder displacement is cranial along the floor of the abdomen. If prostatomegaly is eccentric, as often occurs with large cysts and abscesses and occasionally with tumors, the direction of bladder displacement may be different. A cyst or abscess occasionally may extend dorsal to the bladder (see Fig. 41-2). Alternatively, with ventral prostatomegaly the bladder neck may be elevated (Fig. 41-4). Benign prostatic hyperplasia rarely results in asymmetric prostate gland enlargement. The more severe the enlargement of the prostate gland, the farther cranially the bladder will be displaced (Fig. 41-5). Extreme enlargement may also results in obliteration of the normal triangle of fat formed by the caudal ventral bladder and the prostate gland. The other major radiographic sign of prostatomegaly is dorsal displacement of the colon (see Fig. 41-1). Prostatic enlargement may also cause narrowing of the lumen of the colon or rectum. This compression may be visible radiographically, or the colon may simply become confluent with the prostate mass at the pelvic inlet. A tremendously enlarged prostate gland displaces other abdominal organs cranially. Huge prostatic lesions usually lie on the floor of the abdomen, so some dorsal displacement of the remainder of the abdominal contents occurs. Prostatic and paraprostatic cysts may become so large that they reach almost to the costal arch.13 Masses of this magnitude cause organ displacement so severe that the actual source of the mass may be difficult to determine without using special radiographic procedures or sonography. Prostatic disease that results in urethral stricture may result in severe urinary bladder distention, which is then secondarily responsible for the displacement of the abdominal structures cranial and dorsal to it. Prostatic size that exceeds 90% of the distance from the pubis to the sacral promontory is suggestive of a mass lesion (cyst, abscess, or neoplasm).23 The actual degree of prostatic enlargement varies tremendously, however. For example, prostatic size may vary from slight enlargement to 10 times normal size for benign prostatic hypertrophy, and the gland may actually decrease in size in chronic prostatitis. Therefore if prostatic cysts or abscesses are present, the prostatic silhouette may be as great as 20 or more times normal size, or the degree of enlargement may be minimal. Acute prostatitis and neoplasia do not usually cause severe enlargement, as is seen with hypertrophy and cyst formation. Some small in situ prostatic tumors are not recognized until the animal is examined for another problem, such as cough or lameness caused by metastasis, or they may be discovered as an incidental finding at postmortem. Paraprostatic cysts and abscesses usually have well-defined margins that are easily seen (see Fig. 41-2). An occasional abscess is poorly marginated, although this is the exception. A cyst or abscess may occasionally form in the pelvic canal; such lesions may not be readily visible on survey radiographs or produce the usual displacement of the bladder.24 These lesions do, however, produce marked displacement and compression of the rectum and are therefore recognized as an intrapelvic mass. Distinguishing a cyst from an abscess on the basis of radiographic examination alone is impossible.

The Prostate Gland

Normal Anatomy and Radiographic Appearance

Diseases of the Prostate Gland

Clinical Signs

Radiographic Changes

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Prostate Gland