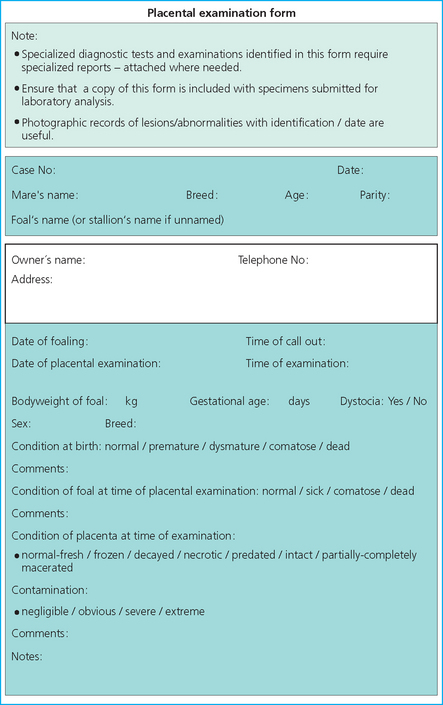

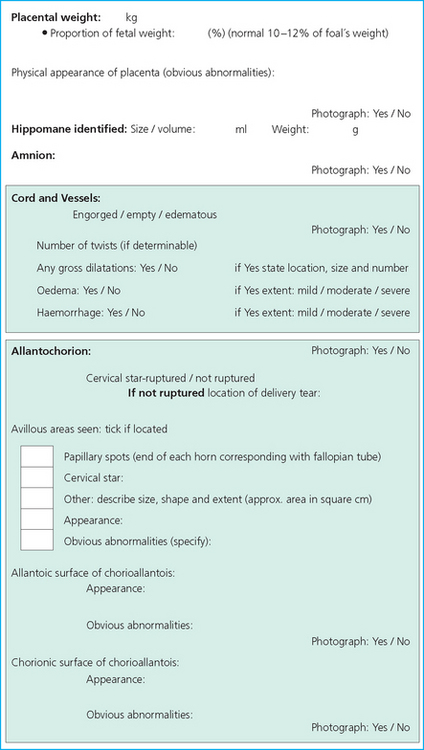

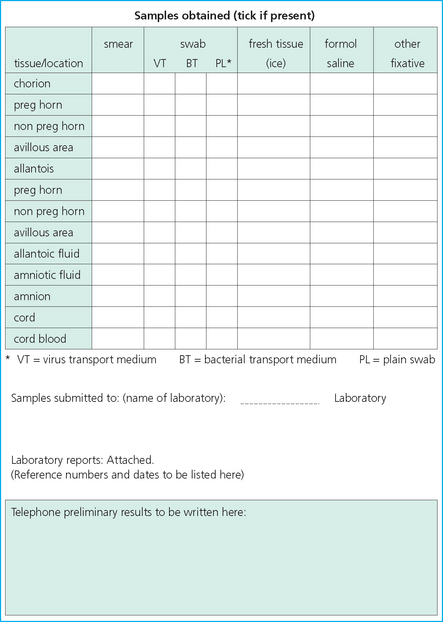

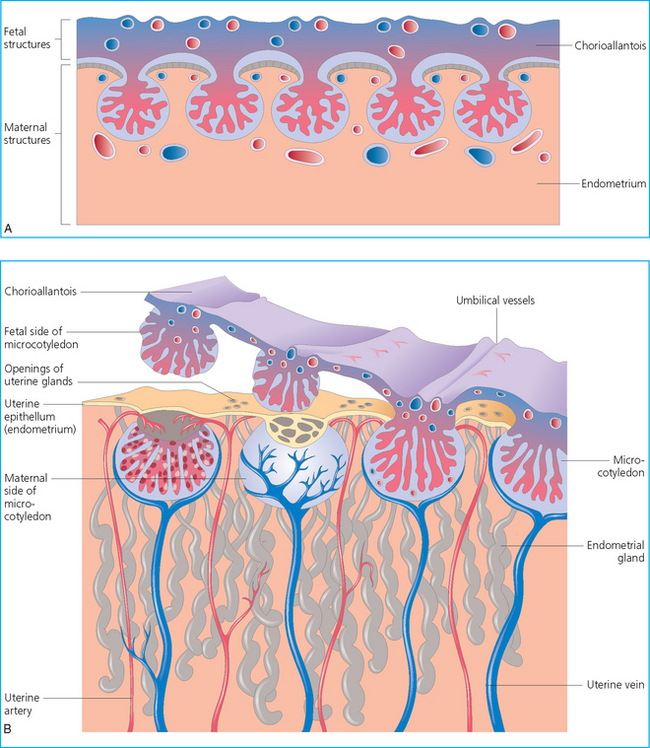

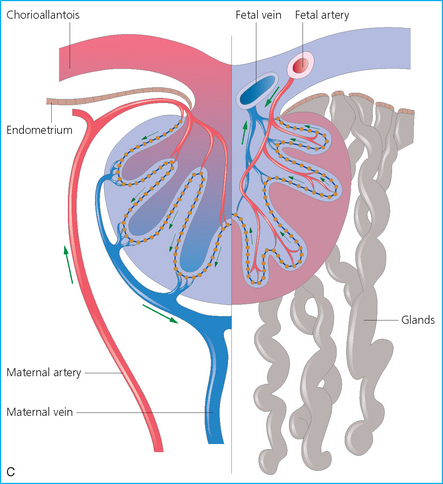

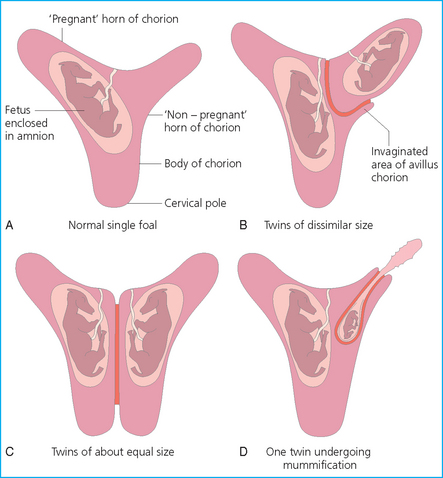

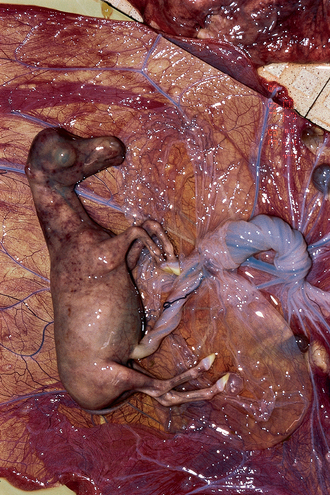

Chapter 9 The equine placenta can be defined as diffuse, microcotyledenary and epitheliochorionic in character. The structure of the placenta and its relationship with the maternal endometrium are illustrated in Fig. 9.1. Fig. 9.1 (A) The macroscopic structure of the mare’s placenta, illustrating microcotyledonary structures. (B) The mature equine placenta, showing the nature of the cotyledons. (C) The vascular arrangement of an equine placental microcotyledon. This placental arrangement has a number of significant implications: • Placental transfer of nutrients to the foal is relatively poor; only one foal can be fully supported. • The entire endometrial surface is required to provide adequate nutrition and gas exchange for a single fetus. • Areas of scarring on the maternal endometrium do not have the normal structure that allows placental attachment and transfers, and are avillous. The result of endometrial scarring or other avillous areas is the loss of effective transfer capacity. The extent of the deficits is reflected in deficiencies of growth or maturation in the foal. Minor placental inadequacy as a result of endometrial scars or cysts may have no detectable effect on the foal’s well-being, but more extensive ones will have an increasing influence. Thus, a foal born to an affected mare may be less developed than it should be. • If twin pregnancies are present, the problem of avillous areas of endometrium is relatively minor. The problem here is that the two placentas will abut each other and so the placental surfaces will reflect avillous areas that do not correspond with endometrial damage (Fig. 9.2). This may perhaps explain the significant number of abortions or stillborn foals and the widely held belief that twins are usually disastrous. However, it is also important to realize that a very small percentage (<1%) of twins are born relatively normal and can also grow well and mature into normal adults. More commonly one foal is better than the other and the large majority of twin births result in poorly grown foals that do not adapt well to extrauterine life. A mare that is known to be carrying twins or has previously had twins is therefore classified as high-risk (see p. 252). Proper management of a twin pregnancy at an early stage can reduce the risks of twinning (see p. 242). Fig. 9.2 Various types of twin placentation. (A) One twin occupies the uterine body and one horn and possesses 70% of the functional surface area. Where the two chorions abut there is usually a degree of invagination of the smaller into the other. (B) The chorion of one twin almost totally excludes the other, occupying the uterine body, one horn and most of the other. (C) Equal division of surface area with no invagination of one chorion by the other. (D) One twin undergoing mummification. • Placental transfer of large protein molecules is not possible. There is no effective/significant acquisition of immunoglobulins before birth. Consequently, the newborn foal is best regarded as immunologically naive. • There is little chance for transfer of infective organisms to the foal without concurrent placentitis, and abortion will commonly ensue in such cases. Even minor placental inflammation can result in rapid abortion or significant compromise in the development of the foal. Therefore the health of the pregnant mare is critical for the delivery of a healthy foal at full term. Serious infections carry a significant danger of early termination of the pregnancy. • Endometrial bleeding, such as is seen in the human hemochorionic placentation, is not possible. Significant blood loss at parturition usually means maternal (cervical, uterine or vaginal) trauma or premature rupture of the umbilical cord. Fresh bleeding after delivery of the foal (and the placenta) is usually a result of uterine, cervical, vaginal or vulvar damage. • Premature separation of the umbilical cord is a relatively frequent event in mares foaling under disturbed conditions. In this situation, the foal can be deprived of up to 1.5 liters of blood.1 This can result in considerable problems with metabolic acidosis and failure to adapt quickly to the free-living state.2 There is debate about the significance of the early separation of the cord and the importance of the blood remaining in the placenta.3 However, it seems reasonable that a foal will be slower to adapt and may be more susceptible to infection if it is deprived of the maximum amount of blood. • Any factor that adversely affects the intimate relationship of the placenta with the endometrium has the potential to cause serious problems, such as abortion, fetal reabsorption, deformity, or neonatal infection or compromise. The problems associated with placental retention in the mare are described on p. 313. The stud manager or groom should be asked to write down the findings as the clinician dictates them. It is unwise to rely on memory. An examination form can be useful in ensuring that nothing is omitted and that the results are recorded correctly. (An example of a suitable form is shown in Fig. 9.25 at the end of this chapter.) In an increasingly litigious society, a meticulous record of events should be kept. i. Remember that the placenta may carry infective organisms. ii. Leave protective boots and overalls on the stud to be washed. iii. Perform normal hygiene precautions (hand-washing and changing of overalls, etc.) before and after examining the placenta. iv. Always examine the healthy prepartum mares first, then the foals and other mares, and finally the placenta. • Disposable gloves/apron/mask. • Scalpel handle and blade (preferably disposable). • Sterile swabs with bacterial and viral transport medium. • Disinfectant for washing up afterwards. • Notepad and paper; record findings as they are identified (it is often useful to dictate to the stud groom as the procedure is performed or use a tape recorder). A suitable protocol is shown at the end of this chapter (pp. 340–342). • A refrigerator and freezer are also useful, but potentially infected specimens must never be stored in a freezer or fridge that also contains other material such as colostrum or plasma. • If there is a possibility that viral agents are involved, a pack of dry ice is often useful as many specimens deteriorate markedly unless cooled quickly. • The normal fresh (wet) weight is about 10–11% of the foal’s body weight4 (e.g. the placenta of a foal born to a multiparous Thoroughbred mare should weigh 4.8–5.5 kg). • A placenta that is heavier than expected may signify edema or inflammatory changes, or the presence of an abnormal amount of fetal blood (suggestive of possible early cord separation). • A placenta that is lighter than normal is usually immature, incomplete or has significant avillous areas. It is essential to examine the placenta thoroughly from both sides (chorionic and allantoic) and to examine the amnion and the cord. Failure to do this could result in failure to recognize vital clues that might impact on the foal and/or the mare.5 i. Place the placenta on a clean dry surface (e.g. concrete floor) well away from any area where other horses might make contact with it (it might carry infectious agents). ii. Lay the placenta out in the shape of an ‘F’, the way in which it was delivered (see Fig. 9.3). The smooth gray, shiny allantoic surface of the allantochorion is exposed (this is the inside of the chorioallantois; it should not be confused with the thinner, tough, smaller amnion, which should be identifiable as a separate entity). Fig. 9.3 Laid-out placenta viewed from the allantoic side with amnion and cord attached, showing the normal distribution of the chorionic vasculature. It is important to recognize these so that abnormal and missing portions can be identified. iii. The bottom leg of the ‘F’ is the cervical end; the cervical star and rupture line should be situated here. The vertical part of the ‘F’ corresponds to the uterine body. The larger upper (longer, wider and thicker) side-arm of the ‘F’ corresponds to the pregnant horn, and the lower, smaller and narrower side-arm corresponds to the nonpregnant horn. iv. The whole visible allantoic surface should be examined carefully, then turned over to inspect the other side. Particular care must be taken to examine any area that may indicate uterine injury from the foal’s feet or legs. This may be the only outwardly detectable indicator of trauma to the uterine wall. v. The integrity of the blood vessels that lie on the allantoic surface should be examined: missing portions of the placenta are characterized by blood vessels that do not correspond; tears in the membrane can be recognized when the vessels can be re-aligned accurately. vi. The placental blood vessels are examined in detail for the presence of any inflammatory margin, which is characteristic of some bacterial infections (particularly those that are liable to cause septicemia in the foal such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp.). The umbilical cord should be examined closely for evidence of abnormal twists and bruising or other damage. The normal cord has a number of regular nonobstructive twists and shows no evidence of hemorrhage at any point (Figs 9.4, 9.5). Fig. 9.4 A normal pony fetus showing a normal cord (with regular, nondilating twists and no obvious urachal dilations). Fig. 9.5 A newborn foal with an abnormally long cord. Note the even, regular and nonobstructive twists in this case. i. If the placenta is very fresh it sometimes useful to collect a sample of blood from the free end of the umbilical vessels. ii. The umbilical vessels should be checked for defects or areas of bruising or other changes. iii. The cord in the Thoroughbred is normally less than 84 cm in length.6

THE PLACENTA

THE NORMAL PLACENTA

EXAMINATION OF THE PLACENTA

Step 1: Prepare by appropriate dress with protective coveralls, gloves, and boots

Step 2: Prepare all equipment required

Step 3: Weigh the placenta

Step 4: Examine the placenta

Examine the umbilical cord and the amnion

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree