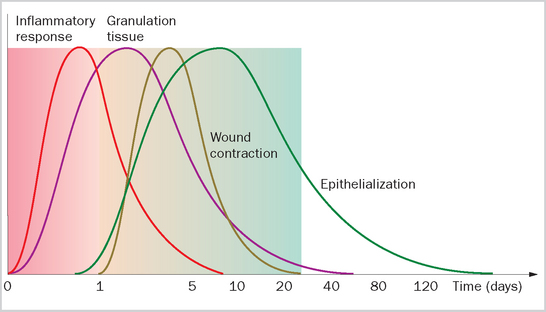

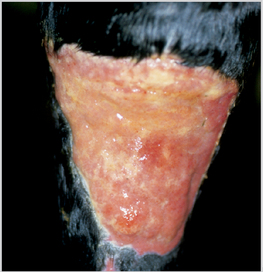

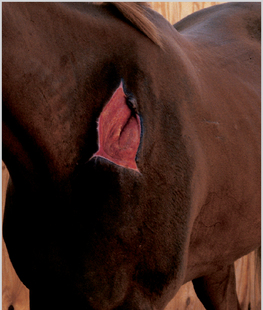

3 Healing is a complex process that, for descriptive purposes, is arbitrarily divided into three temporally and spatially linked stages (Figure 12): Many factors have been identified as having an influence on wound healing; however, any individual factor that adversely (or more rarely beneficially) affects any component of the healing process inevitably carries a penalty (or reward) in the rate and quality of reparative processes (see p. 25). Blood and fibrin flow into the wound site and form a fibrocellular clot, comprising mainly fibrin and fibronectin with the normal blood cells enmeshed within it (Figure 13). The clot serves to limit blood loss and provides a scaffold for the formation of a new matrix that will facilitate the migration of cells. The migration of phagocytic cells is vital for the natural debridement of the wound (Figure 14). Foreign matter and bacteria are removed, and non-viable tissue is demarcated and gradually separated from the viable areas. Figure 13 A fresh laceration on the shoulder of a racehorse showing tissue damage. This represents the earliest stages of the acute inflammatory response with clot formation. Healthy sutured wounds are normally covered in 12–24 hours. Full thickness wounds only epithelialize after formation of a granulating bed, necessitating a lag phase of 4–5 days (Figure 15). Migration of fibroblasts and fibroplasia results in a major gain in tensile strength at 5–15 days in the sutured wound. Granulation tissue comprising of a loose extracellular matrix and increasing numbers of fibroblasts and vascular elements begins to develop 3–6 days postinjury and continues until epithelialization occurs (Figure 16). Figure 15 The mid repair phase. Note the advancing epithelial margin and the central red granulation tissue bed. Figure 16 Late repair phase with a healthy epithelial margin and a flat pale granulation tissue bed. Figure 18 A partially healed wound showing an epithelial margin and evidence of contraction (note the contraction lines, arrows).

The Pathophysiology of Wound Healing

Healing

Inflammatory and Debridement (Demarcation) Phase

Repair (Proliferative/Granulation) Phase

Maturation Phase (Epithelialization and Contraction) (Figures 18, 19)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Pathophysiology of Wound Healing

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

. Healing

. Healing . The Healing Process

. The Healing Process . Wound Contraction

. Wound Contraction