Chapter 11 At the moment of birth the lungs must expand and the pulmonary circulation ‘switched-on’ to ensure a perfect ventilation–perfusion match between the two sides of the circulatory system. The change to pulmonary breathing and the circulatory adjustments that must accompany such a change within minutes of birth must be perfect if the foal is to survive and be able to move quickly to ensure safety.1 Up to this point the blood from the pulmonary artery is shunted via the ductus arteriosus into the aortic circulation as a result of the high resistance afforded by the collapsed lungs and the relatively low aortic pressure. Oxygen-saturated blood arriving in the caudal vena cava from the placental vessels passes through the foramen ovale to the left atrium so that the brain receives freshly oxygenated blood. This pathway is obliterated within the first few weeks of life.2 The position the foal adopts also influences the oxygenation of blood. A foal in lateral recumbency may have a markedly lower partial pressure of arterial oxygen than one in sternal recumbency. This forms one of the most important principles of the management of neonatal foals. Also, the chest wall of the newborn foal is very compliant and so any respiratory disorder may have a disproportionate adverse influence on lung efficiency.3 Although congenital defects of the heart and great vessels are rare, up to 90% of newborn foals have obvious continuous murmurs associated with a patent ductus arteriosus that are audible over the left base of the heart for the first 15–30 minutes of life.4 In most cases the murmurs will not be audible by 72 hours, but some may persist for some weeks.5 Murmurs are also commonly associated with sepsis, fever, anemia, etc.; these may vary from day to day. If cyanosis is present with a murmur it may indicate: • Respiratory distress syndrome or pneumonia with functional murmur. • A significant congenital heart lesion resulting in pulmonary overcirculation/edema. • Complex heart defects with right–left shunting, causing systemic arterial desaturation. Arrhythmia, including atrial fibrillation, atrial tachycardia and ventricular depolarization, is also common in newborn foals within the first 15–30 minutes of life. However, although such events could be alarming they are almost invariably due to high vagal tone and will resolve spontaneously over a short period.6 It may be unwise to perform an electrocardiographic examination on a very new foal because the results may be misleadingly alarming. Differentiation of the abnormal is the challenge for the clinician. Milk is the source of nutrients for the neonatal mammal and the composition of the mammary secretion changes considerably with time.7 In the first hours after birth the milk is rich in immunoglobulins (colostrum). It is tempting to assume that milk provides all the nutritional requirements for the foal. However, in the longer term this is not necessarily so; foals need to supplement the milk feed with other ingesta within weeks of birth and will often be seen to take grass or hay within days of birth. Although natural mare’s milk is used to provide the formula for the preparation of artificial milk supplements, it does contain a delicately balanced variety of essential nutrients, including vitamins, minerals and enzymes, and artificial milk replacers are unlikely ever to match the gold standard of normal milk for any particular species. The normal foal has a defined demand for food materials, but the abnormal or sick foal will inevitably have an increased demand for all the components. The demand for energy is often at least 50% above normal and can be much higher. The same applies to protein and fats as well as minerals and vitamins. Premature foals require extra food to complete organ maturation, but infection, fever, etc. place extreme demands on the foal’s ability to ingest enough raw materials. In reality, a sick foal often has a reduced appetite and so can easily fall into a downward spiral. The specific requirements of the normal newborn foal are: Urinary excretion begins during gestation, with passage of urine into the bladder and then into the allantoic space. A smaller volume of urine will pass into the amniotic fluid via the urethra. The mean urine production in a neonatal foal is around 145–155 ml/kg bodyweight per day.8 This figure is far higher than in mature horses. These factors can be explained simply by the fact that the neonatal kidney is not functionally mature at birth and so renal concentration of urine is much less efficient than in adult horses. Foal urine is frequently more dilute than that of adult horses. The naturally high fluid intake and the lack of concentrating ability means that a foal’s urine has a naturally low specific gravity. The inability to concentrate urine means that it may remain relatively dilute in the face of dehydrating conditions that might otherwise be expected to cause urinary concentration. Foals also often have a relatively high urinary protein concentration9 and this can be significant, even in the normal foal. Furthermore the ability of the kidney to withstand toxic insult and to excrete some drugs etc. efficiently may be very immature. Therefore, drugs and chemicals that damage renal tissue might be expected to have an enhanced toxicity in foals. The first passage of urine is an important event with respect to neonatal assessment (see p. 371). Colt foals usually pass their first urine at around 5–6 hours of age. By contrast, filly foals may delay their first micturition up to 10–11 hours. Observation of the first and subsequent micturition is an important stud procedure and the timing of the first natural urination has implications for those foals that have urinary tract defects such as patent bladder or ruptured ureters. The neonatal foal is born wet and even in the best of circumstances will have to withstand a thermal shock at the time of birth. The ambient temperature is rarely high enough to overcome heat lost by evaporation or by direct loss into the cold undersurface. The considerable muscular effort that foals exert at the time of birth will compensate for some of this, but there is almost inevitably a fall in body temperature at birth.10 Body temperatures below 37°C are regarded as hypothermic and can precipitate a shock-like state. Significantly, hyperthermia can also have serious effects on the foal and temperatures above 40°C can cause convulsions and coma. The concept of a risk category for foals11 has been used for many years and has been instrumental in saving many lives. A system involving three broad categories, in which the foal is classed as high-risk, moderate-risk or low-risk, is most widely used.12 This is simple and serves the purpose well. A two-category classification is a simpler method that avoids the equivocal moderate category and has the advantage that more foals will be classified as high-risk and are therefore likely to be monitored more closely. The recognition that a problem might be present will enable the clinician to take pre-emptive measures to minimize any clinical consequences. On the basis that prevention is better than cure, the system has much to commend it. The concept should be used to guide the level of supervision and interference for a newborn foal. All management strategies for pregnant mares should be directed towards detection of potential or actual problems before they are so advanced that therapy may not be effective. • Risk factors can be predicted from an accurate history of the mare and the pregnancy. • Some of the factors that direct the classification of risk category of the foal will arise during the delivery or immediately afterwards. Therefore, while a foal could fit into the low-risk category until delivery it could be reclassified into a higher risk category as a result of events during or immediately after delivery. The clinician will need to be flexible in the classification and take appropriate steps to ensure that the foal has the best possible chance of survival. These are cases in which there is a significant danger to the life of the foal as a result of: • Maternal circumstances and conditions. • Events occurring around and during parturition. • Conditions and circumstances arising immediately after delivery of the foal. Factors that are present at any stage before birth may have a profound effect on the prognosis for the pregnancy (see Table 11.1). In particular, any factors that influence placental nourishment of the foal or subsequent colostrum production are of major importance. • Prolonged or shortened pregnancy. • Discrepancy between size of foal and size of mare and her birth canal. • History of problem foals (e.g. dysmature/premature, neonatal isoerythrolysis, neonatal maladjustment/asphyxia syndrome, congenital defects). • History of previous uterine torsion in present or previous pregnancy. • History of colostral leakage or premature lactation prior to delivery. • Purulent vaginal discharge or vaginal bleeding. • Disease/injury with or without drug administration. • Pelvic injuries (fresh or long-standing), or space-occupying lesions that might alter the dimensions and congruity of the birth canal. • Lameness or neurological disorders that prevent normal behavior and posture prior to and during delivery. • Pyrexia/toxemia/septicemia/endotoxemia. • Poor bodily condition/poor nutritional status (primary or secondary). • Colic/colic surgery/other surgery (cesarean section or uterine torsion)/anesthesia. • Primiparous delivery (especially if suspect behavior) or history of aggression. Factors affecting the process of parturition would necessarily have a profound effect on the viability of the foal (see Table 11.2). Any factor that affects the ability of the foal to adapt (e.g. loss of blood from early cord separation may cause a slow adaptive period and inability to rise) will have significance: • Prematurity (gestational age <320 days) (see p. 372). • Prolonged gestation (overdue foal). • Perineal laceration/rectovaginal fistulae. • ‘Red bag’ delivery (early placental separation). • Premature rupture of fetal membranes. • Colostral leakage/early lactation. • Early (premature) cord separation. • Vaginal blood loss from mare. A foal can be classified as low risk if: • There are no maternal factors that might adversely affect survival of the foal. • Gestation is of normal duration and there have been no complications with the health of the mare during pregnancy (or any previous pregnancy). • Delivery of the foal is normal and without complication or delays. • The adaptive period should be normal with the foal standing within 2 hours and suckling by 3 hours. • Colostral intake is effective and raises the foal’s IgG concentration to over 8–10 g/l. • The placenta is normal and is passed freely. • There are no external dangers (such as infections in other horses, inclement weather, predators, etc.). It is important to recognize the normal events that take place (see Table 11.3) so that any abnormal events can be quickly recognized and appropriate corrective action taken. Unfortunately, there are wide variations in the normal pattern of delivery and neonatal adaptation, thus making the decision to interfere difficult. The extent of veterinary intervention will often depend heavily on the experience of the owner/handler or groom. More experienced grooms may not need anything like as much support and will also often recognize problems earlier than less experienced grooms. Furthermore, the value of the foal and any complications during pregnancy will often dictate the role of the veterinary surgeon. Probably the majority of foalings attended by veterinarians are recognizably abnormal in some respect. • The foal is delivered during second-stage labor. Usually the foal is within the amnion, which usually breaks spontaneously as a result of opposing movements of the forelimbs and head. • The foal takes its first breaths with chest and abdominal movements (usually within 30 seconds of delivery of the chest). There may be a series of initial gasps with neck arching. • The normal respiratory pattern is rapidly established. The newborn foal will show fast and deep breathing; this is accompanied by a dramatic rise in arterial blood oxygen (PaO2) which progressively increases with increasing muscular effort. There are significant other signs for a similar increase in respiration rate (see below). • The mare will usually undergo a period of tranquility (lasting up to 40 minutes), during which time the foal shakes its head and gains sternal recumbency with ‘righting reflex’. Throughout this the mare remains quiet (usually in sternal recumbency) and will often vocalize to the foal. • The foal may show strong blinking reflexes as hearing and vision are established. It may whinny on its own or in response to the mare. The foal’s head bobs up and down markedly, and suckling responses with lips and mouth are present with increasing strength. • The foal struggles and moves to the side of the mare. Usually the cord ruptures at this time, either because the foal moves or because the mare stands up. The cord usually ruptures about 6–8 minutes after delivery at a predetermined site (3–5 cm from the umbilicus). Shorter ruptures may have serious consequences, including internal hemorrhage. Severe tension on the cord at the umbilicus may also cause serious internal bleeding (although this is very rare). Premature rupture of the cord may compromise the foal (up to 25–30% of the foal blood volume can be lost). • The mare nuzzles, licks and encourages the foal. In response, the foal makes its first attempts to stand, usually within 30 minutes of delivery. • Normal foals will stand by around 45–90 minutes after delivery (often with apparent incoordination); they may fall several times before establishing a steady stance and the ability to move. A normal foal may take up to 2 hours before standing, but the longer it takes the greater the likelihood of a problem being present. • The foal then seeks the mare’s udder (Fig. 11.1). This is often aimless at first but increases in accuracy. Once the teat is located a strong suckling reflex is established. The first effective suckling takes place within 60–90 minutes of delivery. In response, the mare will ‘let down her milk’ and the colostrum will be seen to stream from the teats. • After about 30–60 minutes (especially if a feed has been successfully obtained) the foal will lie down again. The foal may make its first energetic steps on rising again, may jump up and down, and may then fall again. All foals have an inherent incoordination and may seem to be ataxic for the first 24 hours. The APGAR system is a scoring system that is used to assess Appearance, Pulse (rate), Grimace (response), Activity (muscle tone), and Respiration (rate). It is a simple method that can be used for the immediate assessment of the foal during the first 3 minutes of birth (see Table 11.4). A more complex system in which muscular activity parameters carry a higher loading can be used in specialist hospitals for older foals (up to 2 hours) (see Table 11.5). Table 11.4 APGAR scoring method for the assessment of a foal within 3 minutes of birth Score: normal, 7–8; moderately depressed, 4–6; markedly depressed, 1–4; 0, dead. • Provided problems are recognized early, even some seriously depressed foals can be saved with effective intensive care. Some conditions arise before birth, so accurate history and careful clinical assessment is vital. Owners can be taught to assess the foal at birth; this does not reduce the necessity for a full examination as soon after birth as possible. • Many high-risk foals look relatively normal at birth and up to 12–18 hours of age. Once problems develop, deterioration is usually rapid. This makes early recognition of problems an important management procedure. • Newborn foals that are high-risk or that show any evidence of respiratory or neurological (or other) compromise, should be subjected to APGAR scoring at regular intervals over the first 30 minutes. Apparently normal foals should be scored only once and then left alone. In performing the following procedures, the groom/veterinarian must balance the need to interfere against the possible disturbance that this creates. If a foal is delivered in a safe clean environment, little interference should be required and routine procedures can be delayed until the foal is standing and has bonded with the mare. • Gravity can be used to help; slope the foal down from the tail end. Lifting the foal by the back legs can be used, but is difficult and very disturbing to the mare. • If necessary use aspiration (short sharp aspirations are better than prolonged suction). Suitable suction/aspiration systems are available in disposable form. • Ventilation can be encouraged by gently blowing into the nose or by using a mask system fitted to a pressure-limited pump. • Ideally the navel should be immersed in a 0.5% solution of chlorhexidine (this should be repeated every 6 hours for the first 24 hours). • The use of povidone iodine for this purpose has been called into question.15 Strong solutions of iodine or tincture of iodine can cause burning and necrosis of the umbilical stump. • Aerosolized antibiotic sprays (e.g. tetracycline) are useful in that they dry the moist stump while applying a dose of antibiotic but have very limited efficacy and short duration. 3. Administration of colostrum by nasogastric tube • At birth, oral nutrient intake becomes the sole source of nutrition and the importance of colostral antibody transfer cannot be overstated. • Newborn foals can easily be intubated. A soft rubber tube (diameter <1 cm) is best and can be passed up the ventral meatus of the nose. Passage up the middle meatus is more difficult and tends to induce significant ethmoidal damage and bleeding. • Always use as small a tube as possible that is consistent with requirements. Enteral feeding tubes are very much smaller and well tolerated, even allowing normal feeding to take place with the tube in situ. • Usually the act of swallowing can be felt and the tube advanced gently but swiftly. The foal should be blood sampled (see below) at 12–16 hours for estimation of colostral transfer (IgG) and for routine hematology and biochemistry (see Table 11.6). At this stage the earliest evidence for impending problems can often be detected. If there is any suspicion of a problem, blood culture should be set up immediately. Cultures routinely take over 24 hours to yield any useful results. Although this can be a valuable prophylactic measure, it is an expensive procedure. Table 11.6 Changes in a foal’s hematology and biochemistry parameters over the first 7 days of life aChanges more quickly if cord ruptures early. bSamples taken in lateral recumbency may be significantly higher: ±50 mmol/l. cSamples taken in lateral recumbency may be significantly lower: ±75 mmol/l. • The minimum number of venepunctures consistent with requirements are performed. • Full aseptic precautions are taken, especially if blood cultures are to be performed. Suitable venepuncture sites, which can also be used for catheter placement, include: The placental vessels provide a good source of blood without the need to interfere with the foal at all immediately after delivery (within 2 minutes). The samples will need to be taken from the ruptured placental vessels immediately the foal is delivered so that the breaking of the cord can be directly observed. Sampling from the intact umbilical vessels before cord separation is simple but may disturb the mare. Placid, experienced mares may allow this to be performed without making any attempt to rise. Arterial blood can be obtained from: • Full aseptic precautions must be taken and pressure applied to the site of puncture for at least 10 minutes after sampling is completed. • Use specially prepared syringes (with heparin) and needles (Pulsator®, 3 ml with 0.7 mm × 25 gauge needle, single use arterial blood sampling system; Concord Laboratories, UK). • Entry into the artery is indicated by the syringe self-filling. • The equine neonate can be difficult to examine effectively particularly when compromised or when very energetic. • Some foals that are severely compromised by respiratory deficiencies can show considerable resistance to being handled and any attempt to forcibly restrain the foal may be counterproductive or dangerous. • A detailed clinical examination should be performed on every foal; it is very easy to miss early signs of diseases that can progress rapidly beyond the point of recovery. The objective of a clinical examination (including the history) (see Fig. 11.2) is to establish: • Foals born at the end of the stud season can be subjected to significantly increased challenge by infectious organisms than early foals. By contrast, the weather conditions and feeding of the mares can be more problematic in the early season. • Many mares foaling in the early parts of the year are required to foal inside; this may add potential challenges to the foal and to the mare. • Does the foal recognize the dam and is teat-seeking direct and effective? • Does the foal appear to see normally? (Does it bump into walls, etc.?) • Is there milk on the foal’s face (indicating that the foal has at least been in the right vicinity)? • Is the mare’s udder full or empty, and is there evidence of milk loss over the lower hindlimbs? • Is there evidence of nasal reflux of milk during or after feeding? • The respiratory rate should be measured before handling the foal if at all possible. • Is there any evidence of abnormal breathing pattern, rate or is there a nasal discharge? • Observe and assess restraint (e.g. ‘flop’ reflex) (see Fig. 11.3). The vital signs should be recorded early, as they are likely to alter significantly with handling. • Respiratory rate and character can be measured and should be assessed before restraint. After the foal has been restrained the chest should be auscultated carefully with a stethoscope. • Heart and pulse rate/quality should be measured (it is wise to check multiple arteries if possible). An abnormally low heart rate is usually a serious indicator of compromise; a very high rate can indicate anemia, pain, infection, or toxemia. • Mucous membrane color and capillary refill time should be measured and recorded. Normal mucous membranes are a uniform salmon-pink color, and the capillary refill time is normally less than 2 seconds. Again it is wise to use all the mucous membranes available as some may be misleading (e.g. a bruised eye). Furthermore, the mucous membrane color may not be a good indicator of the oxygenation status of blood. The mucous membranes may be pale as a result of loss of blood, or icteric if internal hemorrhage, red cell destruction or liver disease is present. The presence of petechial hemorrhage is usually significant and can indicate toxemia or serious septicemic infection. • The rectal temperature is an important parameter for the foal. Subnormal temperatures can be serious but can be the result of errors of technique. Ideally, a digital thermometer should be used and it should be pressed gently against the rectal mucosa. Any abnormal temperatures should be repeated to test the accuracy. The extremities (feet/limbs and ears, nose, tail) should be palpated to detect altered temperature. • Bodyweight should be obtained routinely, but this is unfortunately not commonly done. The weight of a foal can usually be obtained simply by deduction from the total of a handler and the foal on normal bathroom scales. • The body condition score may be very difficult to assess in a newborn foal as the usual parameters are not easy to identify. However, it should be possible to establish if the foal is reasonably covered with muscle and the extent of fat can sometimes be assessed. • The heart rate should be 40–80 immediately after delivery, with rises up to 130–150 while attempting to stand. Over the first 7 days the rate should gradually fall to 60–70. Foals are easily excited or stressed, so handling may cause increases in the heart rate. • Sinus arrhythmia may be present in the first few hours but should then stabilize. Murmurs are common. The ductus arteriosus frequently remains patent for up to 48–72 hours; a characteristic ‘machinery murmur’ (often grade 3–4/5) may be heard predominantly at the level of the base of the heart (i.e. around the mid-point of the chest at the level of ribs 4–5). [The machinery murmur is a continuous, often vibratory, sound that increases and decreases with the changes in arterial blood pressure but which does not disappear at any stage in the cardiac cycle.] • Serious heart defects may or may not have accompanying murmurs, and the associated signs may be subtle or dramatic. • The normal pulse in a peripheral artery is usually only just palpable. Usually the facial, metatarsal and median arteries can be felt with the fingertips. It may be possible to feel the carotid pulse fairly easily deep in the lower quarter of the jugular groove. • Normal blood pressure (measured from a tail cuff applied with the foal in lateral recumbency) is 35–45/85–90. • The distal extremities such as the ears and feet should be warm. • A jugular pulse is not normal. The distensibility of the jugular vein should be assessed; it should fill briskly unless the foal is hypovolemic. • There are few palpable lymph nodes in the normal foal. Enlarged glands may be significant directly or they may be more noticeable if the foal is in poor bodily condition. • As blood is also a part of the cardiovascular system, the color of the mucous membrane and the specific characteristics of a blood sample can be important aspects of the examination. • The resting respiratory rate and regularity of rhythm are best observed from a distance, without restraint or excitement. Thoracic/respiratory function should be very carefully assessed to ensure that nothing is missed. • Immediately after birth the respiratory rate is normally >60 breaths/minute, but this falls after 1–2 hours to 20–40 breaths/minute. • Breathing should require minimal effort, and should be smooth with passive elastic recoil during expiration. There should be equal airflow from both nostrils. • Rapid respiration can be the result of many systemic conditions, including: • Significant respiratory difficulty can also arise from congenital deformity of the airway (choanal atresia, subepiglottic cyst formation, laryngeal deformity or functional disability, tracheal collapse). • During rest and sleep, respiration can become irregular and there may be some snoring/stertor. • Beware of paradoxical chest patterns (the chest moves in and the abdomen moves out during inspiration). Excessive chest or abdominal movement is best regarded as abnormal and should be investigated. The patency of the airway MUST be assessed in any foal showing respiratory difficulty. • Auscultation of the chest is much easier in the foal than in the adult horse, but even in severe pathology (e.g. Rhodococcus equi abscessation) there may be few abnormal sounds. The dependent lung of a recumbent foal may be almost silent. • Percussion of the chest is very useful and under-utilized. • Absence of sounds is possibly more sinister than obvious adventitious noises. • Foals seldom cough or have nasal discharges even in severe disease. • Too few foals are subjected to blood gas studies, ultrasonography, endoscopy and radiography.

THE NEWBORN FOAL

NEONATAL PHYSIOLOGY

CARDIORESPIRATORY ADAPTATION

Cardiac murmurs in foals

ALIMENTATION

RENAL FUNCTION

THERMAL REGULATION

ASSESSMENT OF A FOAL’S RISK CATEGORY

Why is risk categorization useful?

High-risk foals

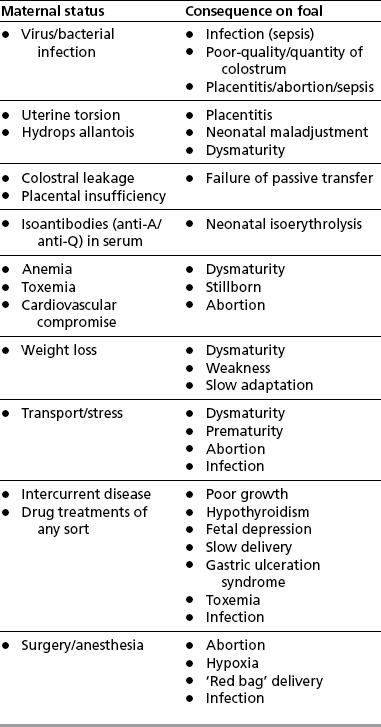

Maternal conditions

Parturition conditions

Factors involving the foal itself or becoming apparent in the foal at delivery

Low-risk foals

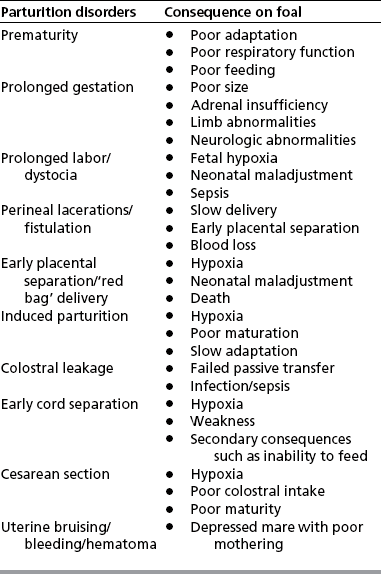

EVENTS FOLLOWING DELIVERY IN THE NORMAL FOAL (THE ADAPTIVE PERIOD)

EVALUATION OF THE NEWBORN FOAL

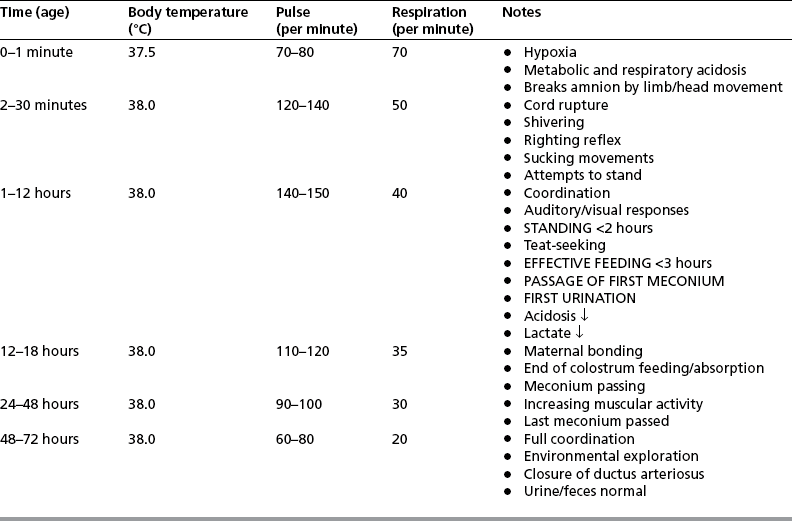

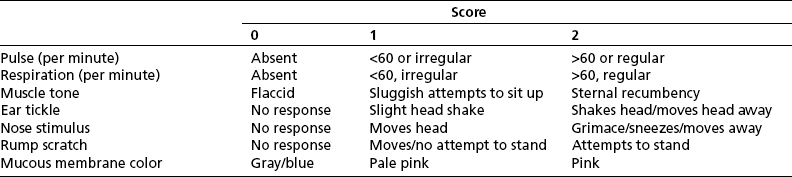

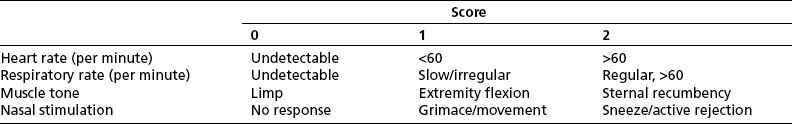

The APGAR scoring system14

ROUTINE VETERINARY AND MANAGEMENT PROCEDURES FOR A NEWBORN FOAL

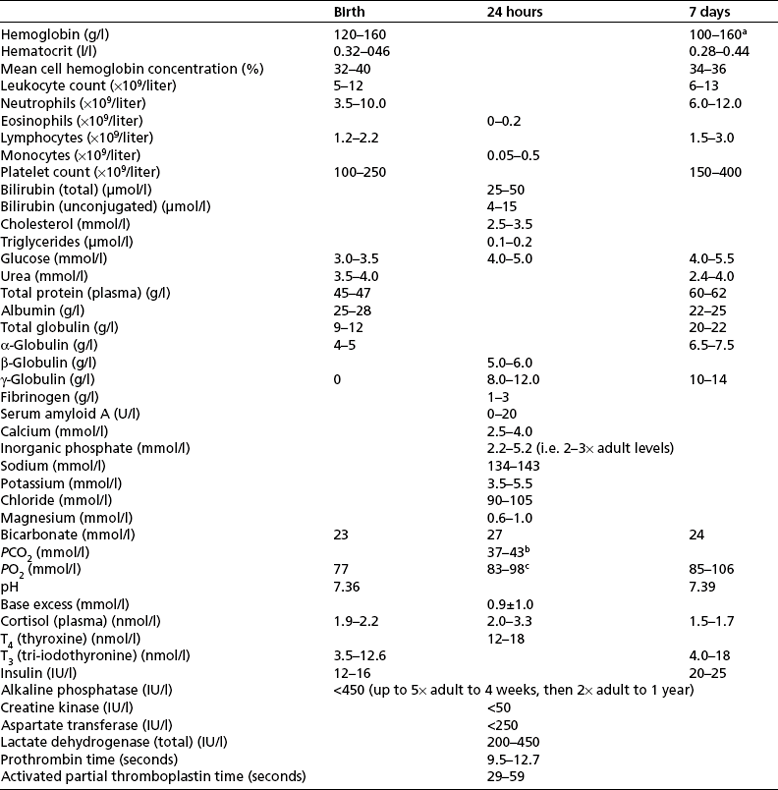

Blood sampling

Venous sampling

Arterial sampling

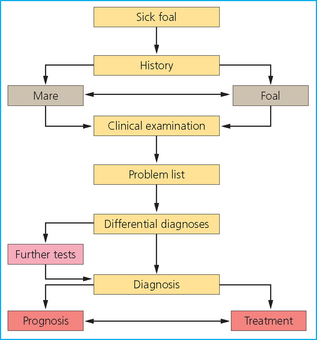

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE NEWBORN FOAL

PROTOCOL FOR EXAMINATION OF THE NEWBORN OR NEONATAL FOAL

Examination of the environment

Examination of behavior

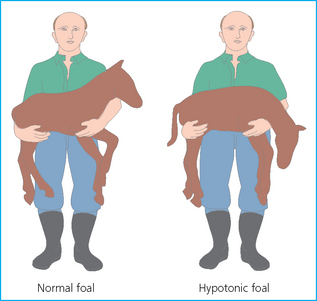

Examination of vital signs

DETAILED EXAMINATION OF THE BODY SYSTEMS

Cardiovascular system

Respiratory system