2 The neurological examination

Examination of nervous system function is achieved by observation, palpation and inducing reflexes and responses. The following section will explain the significance of the tests and how to perform them.

Each section of the examination is simply a part of the jigsaw (Fig. 2.1). The whole picture becomes clear once all the information is in place.

MENTAL STATE

Significance

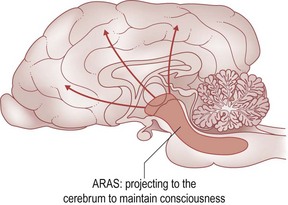

Mental alertness is sustained by a network of neurons within the brainstem (ARAS: ascending reticular activating system) that project to the cerebrum. Damage to either alters alertness. Systemic illness commonly causes decreased alertness in the absence of primary structural neurological disease. Voluntary actions originate from the cerebrum and are influenced by the patterns of behaviour of that species and learnt behaviour imposed by domesticity; it is therefore important that the clinician is aware of normal species behaviour and the level of training (if any) of the animal. Inappropriate responsiveness to the environment indicates cerebral malfunction, or a psychological disturbance (Fig. 2.2).

Examination

Notice if, and how, the animal responds to its name, noise and visual stimuli. Does it walk about the room without taking note of distractions? Does it bump into objects, get stuck in narrow places and have problems reversing out, or turn a particular way when changing direction? Does it stop and appear to stare into space, at a wall or into a corner? None of these behaviours are normal (Fig. 2.3).

Assessment

Describe the abnormal mental state (see page 47) stating what is abnormal about the level of alertness or the appropriateness of the animal’s response to its surroundings. This will act as a better comparison with subsequent examinations than a simple, bald statement of ‘dull’. The clinician will need to decide if the evidence from the history and the examination supports a neurological cause of the altered mental state or not.

POSTURE

Examination

Observe the animal while it sits, stands and moves about. For example, hindlimb weakness can manifest as an arched back with the hindlimbs positioned further cranially under the body (Fig. 2.4).

When sitting, the weak or paralysed hindlimbs may extend straight out between or amongst the forelimbs. The paretic animal is often slow to rise from a sitting position and the hindlimbs may not be fully extended when standing, or could be further apart than normal (abducted) (Fig. 2.5).

Figure 2.5 Husky dog with paraparesis secondary to a chronic T3-L3 spinal cord lesion. Note the muscle atrophy.

Watch for abduction of limbs which may slowly slide out to the side while the animal sits or stands. Note excessive flexion or extension of joints (Fig. 2.6).

Watch for tremors of the trunk and the head at rest and during movement. Offer the animal something to smell and notice if there is any intention tremor of the head. Record the position of the head and if it is turned or tilted or both, and to which side (Fig. 2.7).

GAIT

Significance

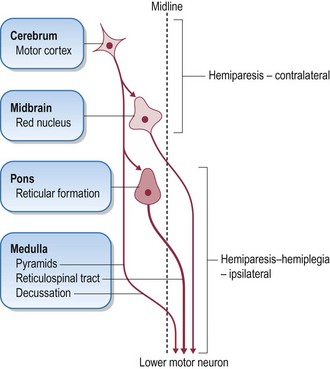

Movement is initiated by the upper motor neuron (UMN), a collective name for the nerve cell bodies within the cerebrum and brainstem and their axons which form the descending motor tracts (fasciculi) of the brainstem and spinal cord. The UMN initiates and maintains normal movement and influences extensor muscle tone to support the body against gravity (Fig. 2.8).

Descending tracts

Observing the gait alone does not provide sufficient information for the clinician to assign the lesion to a specific part of the nervous system (i.e. LMN vs. UMN). Spinal reflexes must be tested and muscle tone must be assessed (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Characteristics of the motor supply

| UMN lesions | LMN lesions | |

|---|---|---|

| Paresis or paralysis | Yes | Yes |

| Spinal reflexes | Normal to increased | Decreased or absent |

| Muscle tone | Normal to increased | Decreased or absent |

| Atrophy | Gradual (disuse) | Rapid (denervation) |

Strength is only one aspect of the gait. Balance and coordination change the direction and extent of limb movement. Cerebral lesions can result in circling, pacing, head pressing; movements which appear normal in execution but apparently purposeless in function, with a propulsive, relentless quality. The circling is towards the side of the cerebral lesion (Fig. 2.9).

Proprioception is the perception of the body in space. Position and movement of the head is chiefly detected by the vestibular apparatus in both inner ears (special proprioception). Receptors in muscles, tendons and joints project sensory information into the CNS (general proprioception). This is then transmitted to the cerebrum (conscious proprioception) and to the cerebellum (unconscious proprioception) by ascending pathways. Projections to the cerebellum enable it to regulate the gait. Cerebellar lesions do not cause weakness. Reduced or absent proprioception causes ataxia. Associated deficits found on examination help localize the lesion to the vestibular system, the cerebellum, the spinal cord, or the cerebrum. (Lesions of the special proprioception receptors are common. Lesions of the general proprioception receptors are rare.) Ataxia is a sensory phenomenon.

Examination

Neurological deficits are noticeable when the animal is walking. Lameness shows up at faster gaits. Observe the gait from the side, front and from the rear. Squat down to observe the footfall of smaller dogs and cats (Figs 2.10, 2.11).

Allow cats to walk around the examination room. If they refuse to move, place them on the opposite side of the room to their owners or basket, which may encourage them to walk.

POSTURAL REACTIONS

Examination

Forelimbs

The animal is supported under the abdomen by one of the clinician’s hands. The other hand grasps the antebrachium, flexing the limb off the ground. The animal is gently pushed laterally, away from the centre of gravity (Fig. 2.12).

The clinician notes any delay in initiating the hopping movement (a sign of weakness, or a conscious or unconscious proprioceptive deficit) and the degree of lateral movement of the tested limb (reduced by weakness, exaggerated with cerebellar disease). A weak limb may collapse, so the clinician must be ready to prevent the animal falling forward. If the animal cannot support weight on the forelimb being tested without collapsing, the clinician should support the forequarters with a hand under the sternum. Do not allow the owner to hold the head or the lead around the animal’s neck as this removes the animal’s weight from the forelimbs making it easier for the animal to hop (Fig. 2.13).

Hindlimbs

A similar technique is used. The body weight is supported by a hand under the animal’s sternum; while the examiner’s other hand holds one hindlimb in a flexed position. This is easier to perform with the animal’s head facing the clinician. The point of supporting some or all of the animal’s weight is to ensure that the limb being hopped is weight-bearing. It is very important, whether testing the fore- or hindlimbs, that the animal remains in as normal an anatomical position as possible, with the spine as parallel to the ground as possible (Fig. 2.14).

Assessment

Strength is subjectively graded as

Wheelbarrowing

assesses the forelimb gait. It is physically more difficult to perform than hopping. The clinician supports all the weight of the hindquarters by placing a hand under the animal’s abdomen. The animal is then pushed forward. Cats almost uniformly refuse to cooperate and lie down which may be misinterpreted as forelimb weakness. It can be difficult to observe the movement of the forelimbs from one’s position at the rear of the animal. It can be difficult controlling the direction the dog walks, and they may struggle when manipulated in this fashion. One way around this is for the clinician to place the other hand under the dog’s head and dorsiflex the neck; this also removes visual clues and may highlight a proprioceptive deficit. It places an enormous strain on the clinician’s back and the information obtained can be more reliably gained by hopping and proprioceptive testing.

Extensor postural thrust

The clinician stands behind the animal and with hands around the thorax, lifts the animal’s forequarters and then the hind off the ground. The suspended animal is lowered to the ground, and its hindlimbs reach out and walk backwards. This is a useful alternative to hopping for testing hindlimb strength in cats. It is not routinely performed in dogs due to their size and weight. The normal response is for the hindlimbs to walk backwards, supporting weight to the same degree. A weak hindlimb is noted by it lagging behind or being dragged (Fig. 2.16).

Proprioceptive positioning (‘knuckling’)

Technique is all important. Begin by supporting the animal’s weight under the abdomen, when testing the hindlimbs, and under the sternum when testing the forelimbs. Weak or painful animals may have normal proprioception but be physically unable to support their body weight and correct the ‘knuckled over’ paw. Some normal animals will only correct the paw’s position when the limb being tested is weight-bearing to some degree. The clinician slightly moves the animal, shifting its weight over to the tested limb to see if this is the case. Proprioceptive testing is a response and can therefore be affected by the animal’s level of alertness. Cats do not tolerate ‘knuckling’ of the hindpaws and it is usually easier to test the hindlimb proprioception with placing responses (Fig. 2.17).

The paper slide test

is harder to perform and less consistent results are obtained. The animal’s paw is placed on a sheet of paper, which is then pulled to the side. The animal should return the displaced limb to a normal position. The problem is that a lot of normal dogs do not seem stimulated enough to return the limb to a normal position, and thus allow the limb to remain on the paper sheet. There is some thought that the paper slide test assesses the proximal limb proprioceptors and the ‘knuckling’ tests the distal limb proprioceptors. This is irrelevant in the clinical setting. Proprioceptive deficits occur because of lesions in the sensory nerves, the ascending proprioceptive pathways, the sensory relay nuclei of the thalamus or the sensory cortex of the cerebrum.

Placing

is another method of testing proprioception in smaller patients. The animal is held under the sternum and abdomen, picked up, and brought towards the edge of a table. The normal animal reaches for the table and places the forelimbs and hindlimbs on the table top without delay. Technique is very important. The animal must be brought towards the table at a speed which enables the animal time enough to move its own limbs. It must not be held so tightly against the clinician’s body that it is unable to freely move its limbs. For this reason it is good practice to test the animal by holding it on either side. Small animals often get their hindlimbs caught in the clinician’s lab coat pocket. Visual placing is the above technique performed without covering the animal’s eyes. Tactile placing is the above technique performed with a hand over the animal’s eyes (Fig. 2.18).

Proprioception is subjectively graded as

Abnormal wear of the claws and overlying fur

Proprioceptive deficits result in abnormal paw position when walking. Scraping, ‘knuckling over’ or dragging the dorsum of the paw against the ground flattens the dorsal surface of the middle two claws, wearing off the overlying fur. Examine all paws. This may not be noticeable if the dog is only walked on grass (Fig. 2.19).

PALPATION

Significance

Pain and joint abnormalities affect the gait and posture. Atrophy occurs with disuse, denervation, secondary fibrosis of muscle, generalized weight loss, and in some myopathies. Muscle enlargement may follow ischaemia, local inflammation, trauma, neoplasia, myotonia, and muscular dystrophy. The distal or proximal limb may be selectively involved.

Warmth of the extremities and pulse quality assesses limb perfusion.

Examination

Thoracic and lumbar spine

Place one hand under the animal’s abdomen and with the other apply gradually increasing digital pressure to the dorsal spine to detect sites of pain. A normal animal tolerates firm pressure and does not collapse. If the animal resents palpation and struggles, wait until the animal calms down, and repeat the palpation to be sure that pain was the cause of the animal’s reaction. Pressure on a painful thoracic or lumbar spine causes the abdominal wall to tense which can be felt by the examiner. It can be confused with abdominal pain. Acute pancreatitis is usually accompanied by vomiting (cf. acute spinal pain). Weak animals may flex the limbs and collapse when pressure is applied to the spine. Some normal animals sit (Fig. 2.20).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree