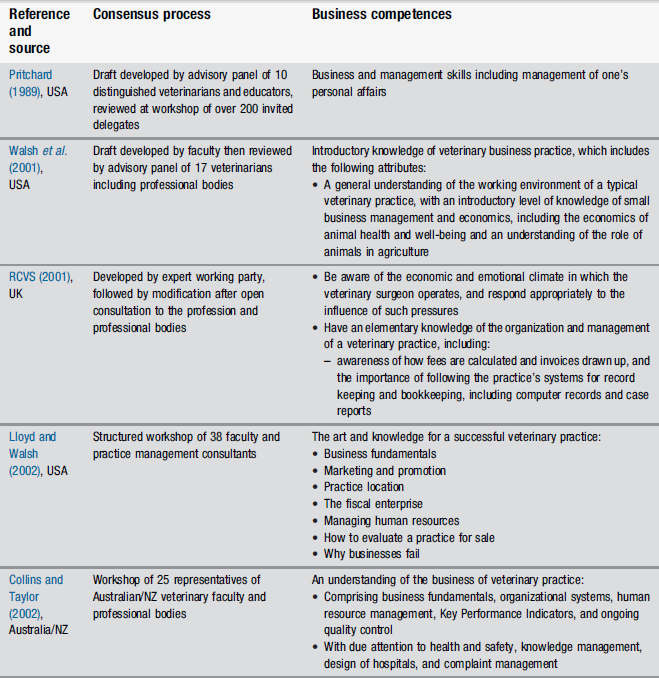

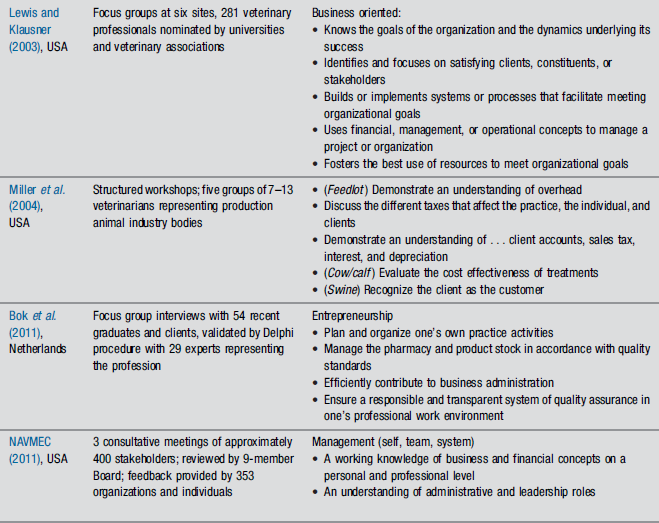

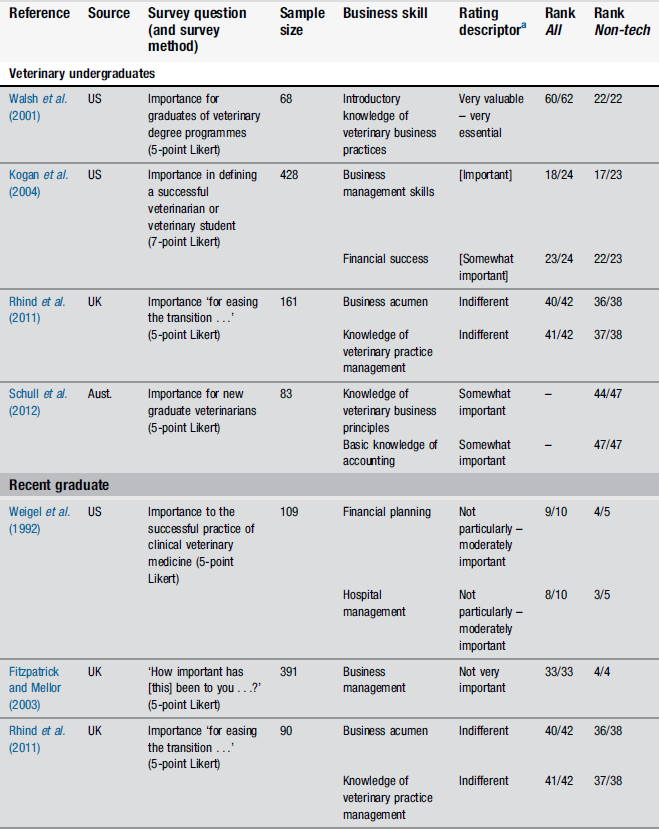

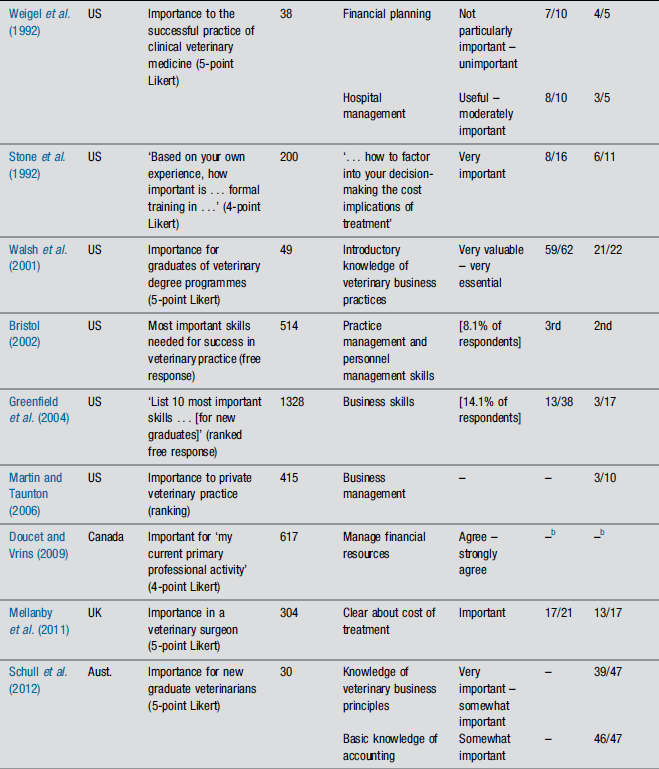

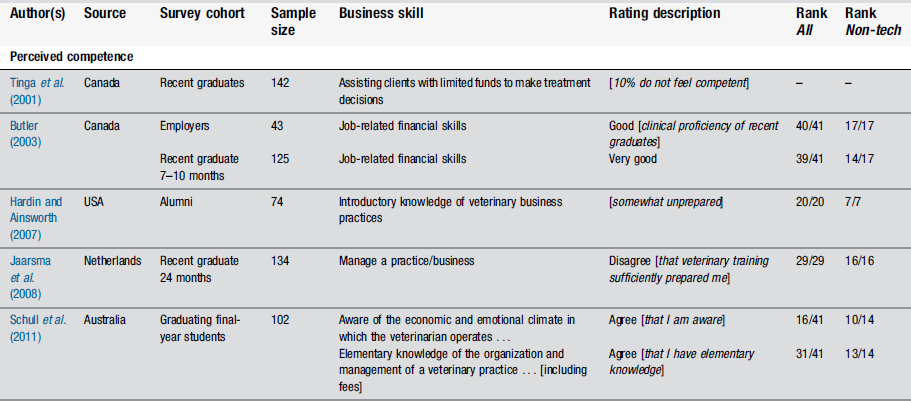

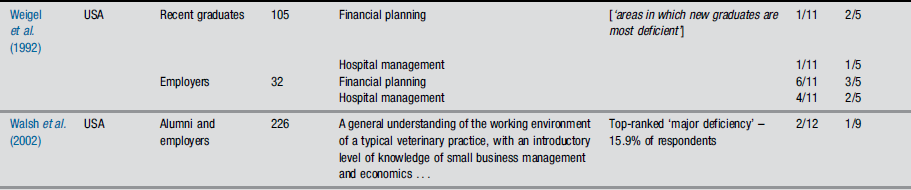

2 Graduate attribute or competence frameworks are becoming increasingly important in veterinary education and accreditation. Several influential international bodies have introduced core competence standards into accreditation procedures. Notably, the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS, 2001) ‘Day One Skills’ and ‘Year One Skills’ framework (which has also been adopted by the European Association of Establishments for Veterinary Education (EAEVE) and the Australasian Veterinary Boards Council), and the recently released North American Veterinary Medical Education Consortium ‘Roadmap’ report (NAVMEC, 2011) include comprehensive yet distinctly different lists of core graduate-level competences. As in human medicine, there has been a recent shift towards the progressive inclusion of non-technical or professional competences – in the veterinary case, including business skills – in addition to the more traditional outcomes of discipline-based knowledge and technical skills. This trend creates the risk that expansive and unprioritized lists of ‘essential’ competences may contribute to curriculum overload, which is recognized as a major concern for contemporary veterinary education (Pritchard, 1989). Despite the importance of these frameworks in guiding international veterinary education and curriculum design, the evidence to justify the inclusion of various competences has rarely been transparent. Very little work has been published to provide direct empirical evidence supporting the importance of various competences to graduate success, or even to document a clear consensus of expert opinion. Thus, while many veterinary competences may be intuitively perceived to be important, few are known to be associated with any tangible professional outcome related to graduate success. Lewis and Klausner (2003) used focus groups to identify six themes around a definition of veterinary professional success: personal fulfilment, helping others, balance, respect, personal challenge and growth, and ‘meeting a level of compensation that meets life needs and permits one to sustain growth in the profession’. Additionally, standard definitions of ‘graduate attributes’ would add employability and effectiveness of the university-to-workplace transition as indices of success at new graduate level. The large, interrelated KPMG (Brown and Silverman, 1999) and Brakke (Cron et al., 2000) studies are routinely cited as establishing ‘a pressing need for business management to be included in veterinary education’ (Lowe, 2010), though both are commissioned economic analyses of the broad state of the US veterinary profession, with little emphasis on graduate-relevant outcomes. Our aim in this study was to comprehensively review and synthesize all contemporary published evidence for the importance of business skills to the success of graduate veterinarians, in order to promote ‘best-evidence’ approaches to undergraduate veterinary education and curriculum design. An open definition of business skills was used, to encompass all aspects including practice management, financial acumen, and sensitivity to economic considerations and their communication. The theoretical approach used for the review was to ‘triangulate’ evidence from several potential sources: (i) perceived importance amongst stakeholders, derived from surveys or consensus-based processes; (ii) evidence of competence or deficiency in recent graduates, and its impact; and (iii) evidence correlating business competences with graduate-level outcomes associated with success. 1. defined veterinary competence lists or frameworks, derived by a broadly consultative or expert, consensus-based method; 2. perceived importance, as surveyed within a stakeholder cohort (veterinary undergraduates, recent graduates, veterinarians, employers, clients); 3. perceptions of competence or deficiency in business skills of recent graduates; or 4. empirical or statistical evidence of an effect on (or correlation with) any graduate-level outcomes related to an unconstrained definition of ‘success’, including but not limited to employability, ease of transition-to-practice, patient outcomes, job satisfaction, or income. (i) papers detailing only opinion, without original research (these were examined for cited references only); (ii) unpublished competence lists referencing a single institution (such as those maintained internally by many veterinary schools) or those formulated without a clearly articulated external or expert consultation process. However, surveys referencing a single institution’s competence list were included, as this represents one standard study design; (iii) papers outside of the veterinary discipline (this is acknowledged as a limitation of this review, as there may be translatable research from similar business-based health professions such as pharmacy). All published competence frameworks reviewed contained business skills, in most cases as a core domain (Table 2.1). However, there was considerable variation in the business competences described, ranging from novice level [e.g. ‘elementary knowledge’ (RCVS, 2001), ‘introductory knowledge’ (Walsh et al., 2001)] to practice owner/manager level [e.g. ‘design of hospitals’ (Collins and Taylor, 2002), ‘practice location’ (Lloyd and Walsh, 2002), ‘leadership roles’ (NAVMEC, 2011)]. There was also variation in the organizational unit described, with some referencing the individual practitioner [e.g. ‘… one’s own practice activities’ (Bok et al., 2011), ‘one’s personal affairs’ (Pritchard, 1989)] while others refer more to the practice unit. One common theme was sensitivity to fiscal or economic considerations. In the Pew Report (Pritchard, 1989), introduction to business management was listed as one of nine ‘essential components of a veterinary education’ (p. 149). While competence lists were unranked, in the Delphi procedure followed by Bok et al. (2011) three of the four ‘entrepreneurship’ competences failed to achieve consensus in the first Delphi round (defined as > 80% score as ‘relevant’ or ‘very relevant’) and were only accepted after discussion and revision. In surveys of the perceived importance of variously defined business skills (Table 2.2), business skills were almost universally ranked near the bottom compared to other surveyed competences, even when compared only to other non-technical skills. Relative rankings were broadly similar across all surveyed cohorts, including undergraduates, recent graduates, veterinarians, academic faculty, and clients. However, the descriptors for the mean or median Likert scale result in most studies remained within the ‘important’ or ‘agree’ range. Business skills were not included in the competence lists of several similar surveys of perceived importance (Coleman et al., 2000, Heath et al., 1996a, 1996b; Hoppe and Trowald-Wigh, 2000). Survey results from the United Kingdom and United States appeared broadly similar. Several studies comparing surveyed cohorts found that veterinarians rated business importance lower than other groups; for example, Rhind et al. (2011) found recent graduates rated practice management of lower importance than final-year students, and Mellanby et al. (2011) found significantly fewer veterinarians than small-animal clients thought being ‘clear about the cost of treatment’ was very important. Similarly, Lane and Bogue (2010a) found that 164 DVM-qualified faculty rated business skills significantly lower in importance than 22 non-DVM faculty. Table 2.2 Rated importance of veterinary business skills and deduced rank aDescriptor of mean, modal, or median Likert scale rating [in square brackets, where estimated]. In an exception to this general pattern, the three surveys of veterinarians finding the highest rankings for business skills were also notable for their use of aggregated free response (Bristol, 2002; Greenfield et al., 2004) or allocation ranking (Martin and Taunton, 2006) methodology, rather than Likert-scaled ratings against predefined competences. When Bristol (2002) asked 514 alumni for ‘the most important skills needed for success in veterinary practice’, the response category ‘practice management and personnel management skills’ was third most frequent, after communication skills and clinical skills. Similarly, Martin and Taunton (2006) found (using a points allocation-based ranking exercise by 415 veterinarians) that business management ranked third in importance, after communication skills and ethical reasoning, from a list of 10 non-technical competences, with no difference in ranking between practice owners or associates. Greenfield et al. (2004) found that 14.1% of veterinarians included proficiency in business management in their top ten most important skills for a new graduate. Lloyd and Larsen (2001) found consensus among practice management consultants and faculty that due to ‘consolidating, competitive, and capacity trends’, business skills would become more important in the foreseeable future. Business skills were rated lowest (or close to lowest) in three studies surveying self- or employer-assessed competence of recent graduate veterinarians. Butler (2003) found a significant difference between ratings of competence in ‘job-related financial skills’ by recent graduates and their employers, suggesting a difference in expected standards. Business competences were rated slightly higher in a recent Australian survey of graduating final-year students against the RCVS Day One competences (Schull et al., 2011). However, business skills were not assessed in several similar surveys of graduate competence (Gilling and Parkinson, 2009; Greenfield et al., 2004). Conversely, business skills ranked very highly in several surveys of perceived deficiency of new graduates (Table 2.3). Walsh et al. (2002) found that knowledge of business practice was both the most frequently cited ‘major deficiency’ and the most frequent suggestion for additions to a proposed list of graduate expectations (111/235 responses). Jaarsma et al. (2008) asked 297 graduates to list topics they felt should have been covered on the basis of their experiences, and practice/business management was clearly the most frequent response (nearly half of the respondents). In qualitative surveys, Routly et al. (2002) identified financial skills as one of three ‘particularly difficult’ demands for the new graduate, reported as causing problems for 47% of respondents, particularly the appreciation of their own time and advice, and difficulties with appropriate estimates. Riggs et al. (2001) similarly found that ‘gaining commercial awareness’ was perceived as one of the most difficult aspects of work by 134 recent graduates, and was rated significantly more difficult by graduates compared to experienced veterinarians. Lewis and Klausner’s (2003) focus groups also identified ‘obtaining business and political acumen – understanding how business works and how business goals are translated into action’ as one of six key ‘environmental challenges’ faced by veterinarians. Table 2.3 Perceptions of graduates’ competence or deficiency in business skills From surveys of self- and employer assessment, and deduced rank (within all competences, and non-technical competences only). For perceived competence, a lower rank order (i.e. higher numerator) indicates the stated skill was rated of relatively lower competence than others surveyed. For perceived deficiency, the higher the rank order (i.e. lower numerator), the more the stated business skill was thought to be deficient.

The need for business skills in veterinary education

perceptions versus evidence

Introduction

Review methodology

Review results

Inclusion in competence frameworks

Perceived importance

Perceived competence and deficiency

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The need for business skills in veterinary education: perceptions versus evidence