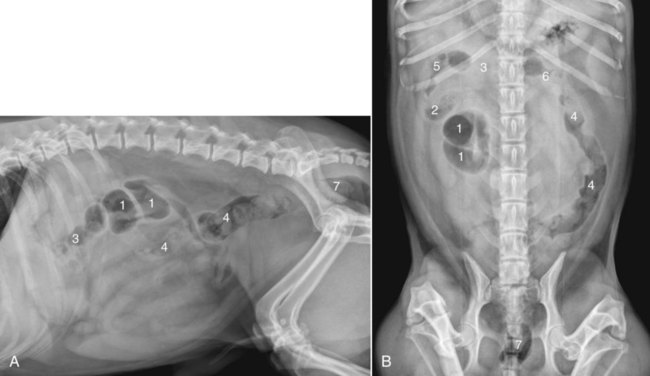

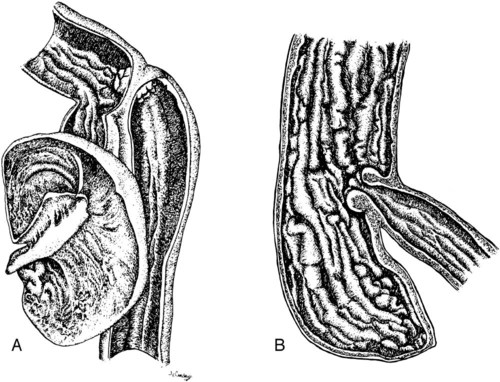

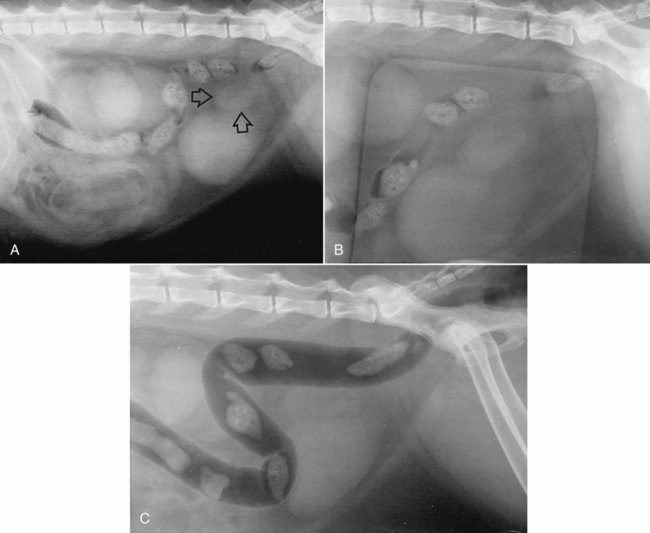

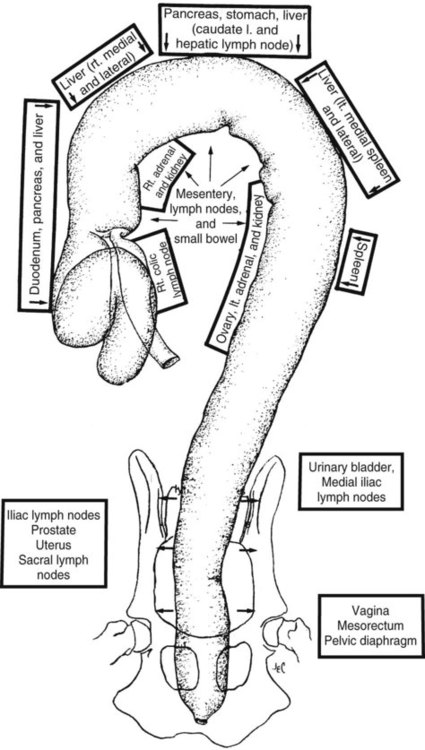

Both survey and contrast radiographic procedures can be used to assess the colon.1–3 Now, however, endoscopy has largely replaced radiographic contrast studies of the colon with the additional advantage of obtaining aspirates and biopsies if needed.4 Ultrasound is a sensitive and practical modality that is less time consuming than most radiographic contrast studies of the colon. It also provides information complementary to endoscopic and survey radiographic findings.5 Although air and feces in the bowel limit the usefulness of colon sonography, near-field bowel wall thickness and symmetry, mural and extramural bowel masses, regional lymph nodes, and intussusceptions can be assessed. Transabdominal cytologic sampling of colon masses can also be obtained with ultrasound-guided techniques.6,7 Less commonly used techniques for examining the colon include rectocolonic lymphangiography, mesenteric angiography, and colonic transit scintigraphy. These techniques enable assessment of anatomic or functional abnormalities but require specialized equipment and expertise.8–10 Computed tomography (CT) is an excellent modality to assess the pericolonic and perirectal areas, particularly for the pelvic canal.11 The large bowel of the dog and cat is composed of the cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal (Fig. 45-1). The cecum, a diverticulum of the proximal colon, has different anatomic and radiographic appearances in the dog and the cat (Fig. 45-2).1 The canine cecum appears semicircular and compartmentalized and normally contains some intraluminal gas. The cecum joins the colon through a cecocolic junction. The intraluminal gas and characteristic shape enable recognition of the cecum in the right midabdomen on most survey radiographs. The feline cecum is usually not visible on survey radiographs. It is a short, conelike diverticulum of the colon with no distinct cecocolic junction and no compartmentalization. The feline cecum rarely contains gas or feces. The shape of the colon is similar to that of a question mark or a shepherd’s crook (see Fig. 45-1). The junction between the ascending and transverse colon is the right colic flexure, and the junction between the transverse and descending colon is the left colic flexure. The ascending colon and right colic flexure are to the right of midline. The transverse colon passes from right to left cranial to the root of the mesentery. The left colic flexure and proximal descending colon are to the left of midline. The distal descending colon courses to the midline and enters the pelvic canal to become the rectum. The rectum is the terminal portion of the colon, beginning at the pelvic inlet and ending at the anal canal. An understanding of the anatomic relation of the large bowel to other viscera is important for the radiographic recognition of diseases of the large bowel and adjacent organs (Fig. 45-3). • The ascending colon lies adjacent to the descending duodenum, right lobe of the pancreas, right kidney, mesentery, and small bowel. • The transverse colon lies adjacent to the greater curvature of the stomach, left lobe of the pancreas, liver, small intestine, and root of the mesentery. • The proximal descending colon lies in close proximity to the left kidney and ureter, spleen, and small bowel. The right ureter travels directly adjacent to the colon wall in the mesocolon toward the bladder neck. • The midportion of the descending colon lies adjacent to the small bowel, urinary bladder, and uterus. Because it is less fixed, the midportion of the descending colon has a variety of normal positions in the caudal left abdomen. In some dogs, the descending colon is positioned along or slightly right to the median axis of the body. Such normal variations are caused by various amounts of ingesta within the bowel, intraabdominal fat, and urinary bladder distention (Fig. 45-4). Some dogs appear to have an excess of length of colon. This finding, called redundant colon, is a variant of normal and is not clinically significant.1,3,3 • The distal portions of the descending colon and rectum are also closely associated with the urethra, the medial iliac, hypogastric and sacral lymph nodes, the prostate or uterus and vagina, and the pelvic diaphragm. Compression radiography of the abdomen is a simple technique that may help clarify the presence of a lesion. When the abdomen is compressed with a wooden or plastic spoon or paddle, bowel or masses adjacent to the large intestine are displaced or compressed, which enhances radiographic conspicuity (Fig. 45-5). More definitive radiographic evaluation of the large bowel usually requires a contrast study with barium sulfate suspension (barium enema), air (pneumocolon), or a combination of barium sulfate suspension and air (double-contrast study). There is a risk of rupturing masses or hollow viscera with this technique, and it should be used with caution. A barium enema is indicated when (1) narrowing of the lumen prevents passage of an endoscope; (2) limitations of the endoscope prevent examination of all the colon and cecum; and (3) a mural or extramural lesion is suspected, but the mucosa is normal endoscopically.4 Survey radiographs should always be made before the contrast study. For a high-quality barium enema, the colon should be cleansed thoroughly. This is best done by withholding food for 24 hours followed by a warm-water enema. The colon should be free of fecal material with a clear effluent visible on the enema performed immediately before the study. Generally, the radiographic technique should be increased by 6 to 8 kVp over the survey technique when barium is used. Although the techniques can vary, barium is administered at room temperature through an inflatable cuffed catheter in the distal rectum.1,12–14 General anesthesia is almost always necessary. Micropulverized barium suspension is the contrast medium of choice for obtaining a smooth coating of the mucosal surface. The colon should be filled slowly by gravity, preferably with fluoroscopic observation. Because fluoroscopic equipment may not be available, and the volume of barium needed to fill the colon is variable, the contrast medium should be given in small increments until the desired effect is seen radiographically. The approximate barium dosage is 7 to 15 mL per kilogram of body weight. Multiple radiographic views, left lateral, ventrodorsal, right ventral–left dorsal oblique, and left ventral– right dorsal oblique, should be made when the colon is distended with barium and again after evacuation of the barium from the colon. The detection of subtle mucosal lesions may be enhanced by a double-contrast study. In most instances, this is done by removing as much of the barium as possible and then inflating the colon with room air through the catheter. Barium enemas are time consuming and must be done meticulously to assess the mucosa, wall, lumen, and adjacent viscera and to avoid artifacts, complications, and technical failures. Partial large bowel contrast studies, which are less thorough, quicker, and easier, may be performed with the introduction of small amounts of air or barium into the rectum using a dose syringe. These studies do not allow visualization of the entire large bowel or of small lesions, such as mucosal irregularities; however, they may enable visualization of large intraluminal lesions and differentiation of the colon from adjacent organs and masses (Fig. 45-5, C). The most serious complication is perforation and subsequent peritonitis, but this can usually be avoided by the use of common sense. Rupture can occur from a cleansing enema, improper selection or use of a barium enema catheter, and overdistention of weakened or diseased bowel, or after a biopsy.15–17 If colonic perforation is suspected before the study is performed, a 15% to 20% concentration of nonionic aqueous iodine contrast medium can be substituted for the barium, but mucosal detail will be diminished significantly.13 A common inconsequential complication is retrograde filling of the distal small bowel, which may obscure visualization of the colon. This can occur in up to one third of dogs and may occur without overdistention of the colon.12

The Large Bowel

Imaging Options for Large Bowel Disease

Normal Radiographic Anatomy

Radiographic Techniques of Large Bowel Evaluation

Survey Radiography

Compression Radiography

Barium Enema

Complications Associated with Contrast Studies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Large Bowel