∗ , Cindy C. Wilson, PhD, CHES † , Aubrey H. Fine ‡ , Jeffery Scott Mio ∗

∗Institute for Applied Ethology and Animal Psychology

†Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

‡California State Polytechnic University

A The role of ethology in the field of human/animal relations and animal-assisted therapy

Dennis C. Turner

26.1 Introduction

As pointed out over 25 years ago (Turner, 1984), the multidisciplinary fields of human/animal relations1 and animal-assisted therapy (AAT) lacked quantitative, controlled observations on behavior and interactions between owners and their pets and between patients and therapy animals. Without intending to belittle the importance of other disciplines involved or interested in this field, the role that ethology has, and could continue to play in research and education on the human/animal relationship and AAT should not be underestimated.

“Ethology” can be defined as the observational, often comparative study of animal and/or human behavior. While in the long run, ethologists are mostly concerned with the biological basis of behavior, their methods and results are not without consequences for the applied fields of human/animal interaction and AAT. As a significant example, one may consider the early studies on dog and cat socialization toward conspecifics and humans (for an excellent summary, see McCune et al., 1995): both species exhibit a sensitive phase of socialization early in life, during which contacts with members of their own species and/or other species (including humans) influence the social inclinations of individuals for the rest of their lives. In dogs, this sensitive phase occurs from four to 10 or 12 weeks of age depending on the author (see Serpell and Jagoe, 1995), in cats from two to eight (towards humans) or 10 weeks of age (toward conspecifics) (Karsh and Turner, 1988; Schaer, 1989; Turner, 2000a). Certainly in cats (Hediger, 1988), probably also in dogs (Reichlin, 1994), socialization can take place simultaneously and independently toward members of the same species and toward humans. That dogs and cats involved in visitation and residential therapy programs are socialized toward both is of crucial importance for both risk management and outcomes, not to mention the welfare of the animals themselves (Hubrecht and Turner, 1998; Turner, 2005a).

Animal welfare laws in many countries require that animals be housed and treated in such a way that all of their species-specific needs can be satisfied and that they are not subjected to stress or pain. Therapy animals are no exception. Regarding behavioral and psychosocial needs, ethological studies provide the necessary background information (Rochlitz, 2005a; Turner, 1995a, 2005b); regarding stress and pain avoidance, studies from both ethology and veterinary medicine (e.g. Broom and Johnson, 1993; Casey and Bradshaw, 2005; Haubenhofer et al., 2005; Haubenhofer and Kirchengast, 2006) are usually the sources of factual information. Hubrecht and Turner (1998), for dogs and cats, and Rochlitz (2005b), for cats, have provided the most recent reviews on companion animal welfare in private and institutional settings, but more work is needed in this area. The International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organizations, IAHAIO, has emphasized the importance of the welfare of therapy animals in its “IAHAIO Prague Guidelines on Animal-Assisted Activities and Animal-Assisted Therapy.”2

There have been relatively few ethological studies of the interactions between pets and people, most of these on cats and many from the research team surrounding the author (Bradshaw and Cameron-Beaumont, 2000; Cook and Bradshaw, 1996; Day et al., 2009; Goodwin and Bradshaw, 1996, 1997, 1998; McCune et al., 1995; Meier and Turner, 1985; Mertens, 1991; Mertens and Turner, 1988; Rieger and Turner, 1999; Turner, 1991, 1995b, 2000b; Turner and Rieger, 2001; Turner et al., 1986, 2003). These have provided information on: the “mechanics” of human/cat interactions; differences between interactions involving men, women, boys and girls and involving elderly persons vs. younger adults; differences in interactions between several breeds of cats; and the influence of housing conditions on such interactions. Many of these results (should) have consequences for animal visitation and (especially psycho-) therapy programs.

As appropriate in any interdisciplinary field, advances in our knowledge about the human/animal relationship and its therapeutic value can also be secured by combining the methods and results of other disciplines with those of ethology. James Serpell (1983) was the first researcher to consider aspects of a companion animal’s behavior in the interpretation of results from a non-ethological study of the human/dog relationship. He found associations between owner affection towards the dog and such dog behavior and character traits as welcoming behavior, attentiveness, expressiveness and sensitivity. Over the years, Turner and his research team have borrowed and expanded upon the methodology of Serpell’s first study to examine the ethology and psychology of human/cat relationships (Kannchen and Turner, 1998; Rieger and Turner, 1999; Stammbach and Turner, 1999; Turner, 1991, 1995b, 2000b, 2002; Turner and Rieger, 2001; Turner and Stammbach-Geering, 1990; Turner et al., 2003). Most recently, Kotrschal et al. (2009) have combined ethological observations of interactions between dogs, respectively cats (Kotrschal, pers. communication), and their owners with personality assessments of their owners and of the animals and discovered many interesting interactions between the two. These types of studies have many consequences for therapeutic work with animals but their potential has not yet been exploited.

What have ethological studies of human/animal interactions and relationships provided us so far? A few examples, based upon the literature cited above, are called for.

From the cat research group of Turner, we now know that: domestic cats show no spontaneous preference for a particular age/sex class of potential human partners, but indeed react to differences in human behavior toward the cats between the different age/sex classes and, therefore, show behavior that would lead us to believe they have preferences. Women and girls tend to interact with cats on the floor while men often do this from a seated position. Children, especially boys, tend to approach a cat quickly and directly, and are often first rejected by the animal for this. Adults usually call the cat first and allow the cat to do the approaching. Women speak with their cats more often than men and the cats also vocalize more often with them than with men. Women are also more frequently approached by cats and the animals are generally more willing to cooperate with them than with men. Retired persons show more tolerance or acceptance of the cat’s natural behavior and desire less conformity by the cats to their own lifestyles than younger adults. When they interact with their cats, elderly persons do so for longer periods of time, often in closer physical contact with the animals, than younger adults, who nevertheless speak more often with/to their cats from a distance.

Differences in cat behavior related to the animals’ sex have been sought but rarely found, although most studies (as well as most cats kept by private persons) were of neutered or spayed animals in past studies. However, Kotrschal et al. (pers. communication) have found a first indication of differences between male and female cats. Individual differences in behavior between cats are always statistically significant and these have had to be accounted for in any analysis of other parameters postulated to affect their behavior. Nevertheless, various personality types, e.g. cats that prefer playing while others prefer the physical contact of stroking, have been discovered (also statistically) among domestic non-purebred animals. Astonishingly, very few observational studies have been published comparing the behavior of pure breed cats. Turner (1995b, 2000b) compared Siamese, Persian/Longhair, and non-purebred cats in their interactions with humans. Differences relevant to potential therapy work with cats were found. Non-observational studies comparing the character traits of many different dog breeds have been conducted with highly significant results for AAA/AAT work (Hart, 1995; Hart and Hart, 1985, 1988). But ethological studies along the same lines are lacking with the possible exception of Schalke and colleagues (2005). Nevertheless, Prato-Previde et al. (2006) have observed gender differences in owners interacting with their pet dogs.

What have studies that combine observational data with indirect, subjective assessments of cat traits and relationship quality by their owners provided? Turner and Stammbach-Geering (1990) and Turner (1991) found correlations that help to explain the widespread popularity of cats, as well as one key to a harmonious relationship between a person and his or her cat: Cats are considered by their owners to be either very independent and unlike humans (who consider themselves, in this case, “dependent”) or they are dependent and human-like. Some people appreciate the independent nature of the cat; others, their presumed “dependency” on human care. The authors also discovered that the more willing the owner is to fulfill the cat’s interactional wishes, the more willing the cat is to reciprocate at other times. But the cat also accepts a lower willingness on the part of the owner and adapts its own willingness to interact to that. This “meshing” of interactional goals is one indication of relationship quality.

More recently, Stammbach and Turner (1999) and Kannchen and Turner (1998; see also Turner, 2002) combined psychological assessment tools measuring human social support levels, self-perceived emotional support from the cat and attachment to the cat with direct observations of interactions between women and their cats. Emotional attachment to the cat was negatively correlated with the amount of human social support the owner could count on and positively correlated with the self-estimated amount of emotional support provided by the cat. Attachment to the cat was found to be the more predominant factor governing interactional behavior rather than amount of human support available to the owner.

Most recently, Rieger and Turner (1999), Turner and Rieger (2001) and Turner et al. (2003) have used psychological tools and ethological observations to assess how momentary moods, in particular depressiveness, affect the behavior of singly living persons toward their cats, respectively, persons with a spouse. They emphasized that these persons, who had volunteered for the studies, were not necessarily clinically depressive. They discovered that the more a person was depressed, the fewer “intentions” to interact were shown. However, the more a person was depressed, the more he or she directly started an interaction. This means that depressed persons had an initial inhibition to initiate that was compensated by the presence of the cat. People who became less depressed after two hours owned cats that were more willing to comply with the humans’ intents, than those of people whose “depressiveness” had not changed or became worse. When not interacting, the cat reacted the same way to all moods of the humans. This neutral attitude possibly makes the cat an attractive pacemaker against an inhibition to initiate. Within an interaction the cats were indeed affected by the mood: they showed more head and flank rubbing toward depressive persons. But apparently only the willingness of the cat to comply was responsible for reducing depressiveness. The authors interpreted their results after a model of intraspecific communication between human couples, in which one partner is clinically depressed (Hell, 1994) and found striking similarities. The potential of these findings for AAT sessions involving cats is obvious.

While Rieger and Turner (1999) and Turner and Rieger (2001) found that cats were successful in improving “negative” moods, but not increasing already “good moods” among single persons, Turner and colleagues (2003) found that a spouse was indeed capable of the latter. Nevertheless, they also found that a companion cat was about as successful as a spouse at improving negative moods.

26.2 Unanswered research questions

Despite the above-mentioned relevant results from ethological studies and those from investigations combining the methods and interpretations of other disciplines with those from direct observations, we have only begun to “scratch the surface” in the ethological analysis of human/pet relationships. This is true for human/cat, but especially so for human/dog relationships. Given the heavy involvement of dogs in AAA/AAT programs, it would be prudent to encourage similar studies of dog behavior and human/dog interactions. In particular, the breed differences in behavior and character traits reported in studies using only indirect methods (Hart and Hart, 1985, 1988) are extremely relevant to therapy work and should be substantiated by independent analysis of observational data. Further work on behavioral differences between cat breeds is also called for as this would be particularly useful for animal-assisted psychotherapists.

Another reason to promote comparative ethological studies of dog/human interactions is the reported difference in general Gestalt of the human/dog vs. the human/cat relationship (Turner, 1985, 1988): dog social life is organized around dominance/subordinance relationships, whereas cat sociality (assuming socialization toward humans in the first place) is based upon “give and take,” mutuality/reciprocity and respect of their independent nature (Turner, 1995c). This basic difference must be considered especially in psycho-social therapy. Sex differences in dog behavior toward humans have been found (Hart and Hart, 1985, 1988; Sonderegger and Turner, 1996), but these need to be further examined in intact (non-spayed and non-neutered) cats. More detailed work on the communication signals used by dogs and cats in intra- and interspecific interactions is also required, in particular comparative studies to assess whether the same signals have the same meaning when directed to another species and how that other species interprets them. Mertens and Turner (1988), Goodwin and Bradshaw (1996, 1997, 1998), and Bradshaw and Cameron-Beaumont (2000) have made a start, but we have much more to discover in this area.

The study of Rieger and Turner (1999; see also Turner and Rieger, 2001; Turner et al., 2003) showed for the first time that moods of cat owners affect their interactional behavior and that the cats can indeed help persons out of a momentary depressive mood. The mechanism through which this probably occurs was postulated, but still needs to be tested; then trials with clinically depressed persons must be conducted. This study also produced the rather surprising (and difficult to defend in front of cat enthusiasts!) result that the cats did not react measurably to the different moods of their owners from the outset, only within an ongoing interaction. However, it is probable that humans (and cats) send out very fine signals (e.g. gaze, see Goodwin and Bradshaw, 1998) not picked up by the ethogram used in this first study. Again, a finer analysis of communication between cats and their owners using video to record facial mimicry, etc. would be helpful.

Other species than dogs and cats are involved in some AAA/AAT programs, reportedly with positive outcomes, e.g. the effects of watching caged birds or aquarium fish in lowering blood pressure and pulse rate are well documented (Katcher et al., 1983) and their presence can significantly improve the quality of life of residents in institutions (Olbrich, 1995). Nature programs (also involving animals) have reported good results in the treatment of ADHD and CD children (Katcher and Wilkins, 2000). Rabbits, guinea pigs, hamsters, etc. are involved in some programs, but also sometimes improperly housed and/or handled. More ethological studies on proper housing of these species and better education of the AAA/AAT specialists using them are urgently needed (see below). Again comparative ethological studies of human interactions with these species would be useful: Turner (1996, 2005c) has postulated differences in the benefits accrued depending upon whether the therapy animal species is interactive and initiative (i.e. establishes contact with the patient of its own volition, such as dogs and many cats do) or simply present during the therapy session as an “ice breaker” (bridge to the therapist) or topic for therapeutic discussion. Presumably many rodent species, caged birds and fish serve this function.

To summarize, it is clear from the above-mentioned studies that ethology and ethological methods have much to offer the field of human/companion animal relations and potentially animal-assisted therapy, but that much remains to be done. We have or can expect information on: how to ensure the socialization of the animals involved in therapy programs or to assess the degree of socialization in animals up for selection; how to properly house, handle and care for the animals involved to minimize stress and ensure their health and welfare, thus maximizing potential benefits to the recipients of therapy; differences in interactive behavior between healthy women, men, girls and boys and between different species and breeds of intact, neutered or spayed male and female therapy animals, which provide baseline information for therapeutic work with less fortunate human beings; matching the animal and recipient of the therapeutic activities; assessing changes—improvement—in interspecific (human/animal) relationship quality which could (should) parallel changes in interpersonal relationship establishment and quality; and the mechanisms explaining why animals work as (co-)therapeutic agents.

It is equally clear that the combination of theories, methods and interpretations from different disciplines can lead to major advances in our understanding of those relations. Therefore, any educational program on human/animal relationships and animal-assisted therapy must, of necessity, be interdisciplinary.

26.3 Setting standards

Equally important as the distinction between animal-assisted therapists, animal-assisted pedagogues, and specialists for animal-assisted activities is the need for these persons to be professionally trained to involve animals in their work. To check the uncontrolled growth in this field and the misusage of terminology, the International Society for Animal-Assisted Therapy, ISAAT,3 was founded in 2006 by representatives of universities and private institutions in Japan, Germany, Luxembourg and Switzerland. The goals of ISAAT are: (1) quality control of public and private institutions offering continuing education in AAT, AAP, and as specialists in AAA, through establishment of an independent “accreditation” board4 ; (2) the official recognition of AAT, AAP and AAA as professional disciplines; and (3) the official recognition of persons who have completed continuing education in an ISAAT member institution either as animal-assisted therapists, animal-assisted pedagogues or specialists for animal-assisted activities.5

The independent accreditation board of ISAAT is charged with controlling: admission criteria for the continuing education program; qualifications of the teachers; the curriculum for its interdisciplinary, theoretical, and practical content and duration; thesis (final report) requirements; examination rules; conditions of study and certification. The interdisciplinary curriculum is expected to adequately cover the items listed in Table 26.1.

Table 26.1 Curriculum requirements∗ for approval and recommendation for full membership in ISAAT

|

∗ A total of at least 225 hours of formal course work and supervised activities. |

At the time of writing, four institutions/programs have been accepted into full membership in ISAAT (=accreditation) and other applications are currently being examined by the board. Quite a large number of programs claim to follow the ISAAT standards; however, they have not been controlled and accepted for membership unless they are listed on the official ISAAT home page. Nevertheless, it is encouraging for the interdisciplinary field of HAI and AAT/AAP that more attention is being paid to standards and quality control and the future looks bright.

B Human/animal interactions (HAIs) and health: the evidence and issues—past, present, and future

Cindy C. Wilson, PhD, CHES

26.4 Introduction

For the second edition of the Handbook on Animal Assisted Therapy, I was asked to set the direction for the research agenda for the human/animal interaction (HAI) field. As I reviewed that paper in preparation for a new chapter in the third edition, the recurring themes, issues, and conundrums surprised me. At the same time, there have been some positive, forward thinking, and moving events that are certainly milestones in the history of the field. My intent is to give a brief overview of research themes and issues that researchers and practitioners currently face in this field. Then, given changes in the field since the last edition, I will

review how HAI and health may currently fit into the expectations of an evidence

summarize strategic research decisions that must be made and operationalized by both researchers/practitioners and funding agents; and last

suggest where we should go from here if we are to improve the health of those research participants we serve through human/animal interactions protocols and programs and our own health.

The field of HAIs remains at an early stage of its development—currently estimated by this author at “late childhood or early adolescence.” The topic of HAIs and health moved from being perceived as “non-mainstream” research to having two major funding initiatives (private and public) directed towards HAI and health. First, the Waltham Centre for Pet Nutrition/Mars™ (i.e. Waltham Centre) and the American Association of Human-Animal Bond Veterinarians (AAH-ABV) issued a request for funding in 2007. In 2009, the Waltham Centre partnered with the International Society of Anthrozoology (ISAZ) and again provided funding for select, peer reviewed proposals. Both of these calls for research proposals were to stimulate new research in the area of human/animal interactions, with particular interest in the impact of pets on the physical well-being of children, the role of pets in the lives of elders, and the impact of culture on the human/animal bond.

Concurrently, substantive experts from a variety of fields (e.g. psychology, sociology, ethology, child and human development, child abuse, clinical medicine, aging, veterinary medicine, nursing, and public health, etc.) were meeting in conjunction with representatives from the Waltham Centre/Mars™ and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development to define research areas relevant to both organizations as well as to the HAI field at large. A series of substantive workshops led to the second funding initiative by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development and a request for funding applications (RFA) entitled “The Role of Human-Animal Interaction in Child Health and Development (R01).” The purpose of this funding opportunity is to build an empirical research base on how children perceive, relate to and think about animals; how pets in the home impact children’s social and emotional development and health (e.g. allergies, the immune system, asthma, mitigation of obesity); and whether and under what conditions therapeutic use of animals is “safe and effective.” The NIH/Mars™ funding opportunity “supports both basic and applied studies that focus on the interaction between humans and animals and the impact of HAI in three major areas: (1) foundational studies of the interaction itself and its impact on typical development and health, including basic research on biobehavioral markers of suitable behavioral traits for HAI and for using domesticated companion animals as models for identifying gene-behavior associations in humans; (2) applied studies (to include but not limited to clinical trials of the therapeutic use of animals); and (3) population level studies of the impact of animals on public health (prevalence/incidence studies, etc.), social capital, and the cost-effectiveness of using pets/animals in reducing/preventing disease and disorders (RFA HD09-031, 2009).” Review of submissions for this RFA is currently under way and there is tremendous excitement within the research community regarding this commitment to the science of human/animal interactions.

The HAI field has moved forward as evidenced by the national and international attention being focused on building partnerships for funding initiatives and continued interaction across disciplines. However, the question remains whether the quality of the science has progressed alongside these initiatives. Several critical papers have been written that have reviewed the evidence supporting HAI. Table 26.2 briefly identifies the studies and notes their conclusions.

Table 26.2 Reviews of the evidence

|

26.5 The physical evidence

Continued evidence mounts regarding the impact of companion animals (CAs) on health. Benefits of pet ownership (PO) are consistent with the goals and objectives of many leading health indicators for diabetes mellitus, physical activity and fitness, mental health, disability, HIV, and heart disease outlined in the national report, Healthy People 2010 (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2005). Of the 28 focus areas identified in Healthy People 2010 (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2005), seven areas (diabetes mellitus, disability and secondary implications, heart disease, HIV, physical activity and fitness, nutrition and overweight, and mental health) are positively influenced by PO. We now know that sedentary behaviors not only contribute adversely to the health burden of PO but also to their animal companions (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996, 2005). The Humane Society of the USA recommends twice daily walking to improve canine health and fitness (“Caring for your dog: the humane society of the United States,” 2005) while the US Surgeon General recommends 30 minutes of exercise/day or approximately 10,000 steps per day. With approximately 65 million dogs in US households (American Pet Products Manufacturers Association, 2006), walking a dog may benefit a large proportion of the US population by increasing their physical activity (PA) and cardiovascular fitness (Kushner et al., 2006). This augmented level of PA may also have significant health benefits for their canine companions (Ham and Epping, 2006). Older dog walkers have been shown to have better health practices and mobility than geriatric non-dog walkers by reaching the US Surgeon’ General’s recommended weekly goal for PA (Thorpe et al., 2006).

The National Household Travel Survey (NHTS), a cross-sectional survey of personal transportation by the civilian, non-institutionalized population in the USA, was conducted by the Department of Transportation. A random sample of households (n = 1,282) was selected based upon the responses to categories of “walking trips for the purpose of pet care” (Ham and Epping, 2006). Among dog walkers (DW), 80% walked at least one or more times for at least 10 minutes and an estimated 59% engaged in two or more walks a day. Nearly half of the adults in the sample who walked their dog two or three times a day easily accumulated 30 minutes or more of walking in a day. This PA contributes to the overall fitness of both the dogs and their owners and improves overall wellness.

In addition to the benefit of purposeful activity, dog walking may also support social aspects of PO health when identified as an effective behavioral mechanism to increase physical activity (Bryant, 1985; Serpell, 1991; Woods et al., 2005). Long-term adherence to walking was reported by many respondents as an obligation to provide their dog with needed exercise. Based upon the dog walker’s logic, the dog is a “buddy” as well as a motivational factor for being physically active. In contrast to other forms of exercise, dog walking is convenient, requires no special equipment, and can be done at any time. This is important because convenience is a consistent predictor of regular exercise for many people (Bautisa-Castano, 2004; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2005).

26.6 Selected psychosocial evidence

A large body of research supports the positive health effects of human companionship (Allen et al., 2002; Friedman, 1983–2009; Parslow and Jorm, 2003; Wells, 2004). The benefits of having a companion, a spouse, or a “buddy” (Cain, 1983; Ham and Epping, 2006) to provide physical and emotional support (Cohen, 2004; Risley-Curtis et al., 2006a,b) are well described. Pets also continue to serve as a source of human social support (Peretti, 1990; Serpell, 1991; Wells, 2005) and emotional support; they also serve as part of a friendship network, bolster their companion’s sense of competence and self-worth, serve as a opportunity for nurturance and love, as well as provide the opportunity for shared pleasure in spontaneous recreation and relaxation (Jennings, 1997; Wilson et al., 1998, 2001; Collis and McNicholas, 2001; Woods, 2004).

There is little doubt that companion animals, especially dogs, have an impact on the health of their companions. Yet, based upon the studies to date, there remains the question of whether these health effects will be found in all individuals regardless of the type of pet, the ethnic group of the owner, or across all age groups. Additional concern remains about these positive outcomes because of a variety of design and methodological issues.

26.6.1 Building the evidence—standards and quality control in research

Defining relevant terms and issues

The use of the term “human/animal interaction” is the best-known term for all relevant research in this area. Within that label would be familiar terms (e.g. animal-assisted therapy, animal-assisted activities, human/animal bond, etc.). All therapies, intervention, and assistance involve “interactions.” However, in the databases of “evidence (e.g. PubMed, Cochrane)” that term does not occur. In fact, the most commonly used database in the USA for health-related topics is Medline and there still is no Mesh heading for human/animal interactions. The closest approximation to access journals remains “bonding-human-pet” (Spitzer, 2009). In Europe, in addition to Medline, another commonly used database for health-related inquiries is Embase. As in Medline, there is no key search term for human/animal interactions.

Defining the evidence hierarchy

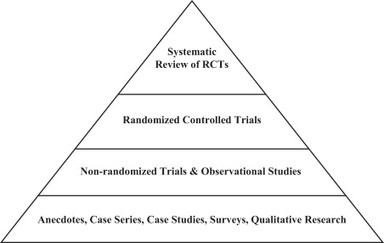

In order to take its place as “evidence-based,” HAI research must advance in the hierarchy. As shown in Figure 26.1, the “evidence” goes from less causal research methods (case reports/studies, case series, surveys, qualitative research, and anecdotes) to increasingly more sophisticated research methods—non-randomized trials and observational studies—to what is considered the “gold standard,” the randomized controlled trials (RCTs). At the top of this pyramid is the most sophisticated of causal research methods, the systematic review of randomized controlled trials—more commonly known as the “meta-analysis.”

Establishing the challenges to HAI research

There are many challenges to HAI research and to building the evidence base. Five of these areas are briefly described:

Challenge 1. Establishing and applying high quality standards of research

HAI research, like all scientific pursuits, attempts to identify outcomes of a particular relationship. To this end, there are six steps of the research process that require the same scientific standards regardless of the area of research.

Step 1: Problem identification and formulation. A research question is posed and its inherent concepts are progressively refined to be more specific, relevant, and meaningful to the field of HAI. As this is done, the feasibility of implementation is considered. Ultimately, the purpose of the study is finalized and the individual aspects of the research project, including hypotheses, independent and dependent variables, units of analysis, operational definitional units of analysis are described, and a robust literature review across all relevant disciplines is completed.

Step 2: Designing the study. The term research design deals with all of the decisions we make in planning a study. Decisions must be made not only about the overarching type of design to use, but also about sampling, sources and procedures for collecting data, measurement issues (internal and external validity and reliability), selection of instruments if appropriate, data analysis plans, as well as a plan for dissemination of outcomes/results. Decisions made in this step are guided by the original problem formulation, the feasibility of the plan, and the purpose of the research. For example, studies designed to address causation require logical arrangements that meet the three criteria of establishing causality (Lazarsfeld, 1959): (1) the cause must precede the effect; (2) the two variables being considered must be empirically related to one another; and (3) the observed relationship between two variables cannot be explained away as being a result of some third variable that causes both of them. This often requires an experimental design. Other questions require other designs; for example, questions about change over time generally require a longitudinal approach.

Step 3: Data collection. Once a study or program is designed, the structure of its implementation is planned in advance. Deductive studies that attempt to verify hypotheses or descriptive studies that emphasize accuracy and objectivity require more structured data collection procedures than will studies using qualitative methods to better understand meanings of certain phenomena or those that are intended to generate hypotheses rather than investigate hypotheses.

Step 4: Data processing. This step of the research process involves the classification or coding of observations in order to make them more interpretable.

Step 5: Data analysis. Processed data are analyzed for the purpose of answering the research question. Commonly, the analysis also yields unanticipated findings that reflect on the research problem but go beyond the specific question asked.

Step 6: Interpreting the results of the analyses. There is no single, “correct” way to plan a research study appropriate to HAI and/or animal-assisted therapy and no way to plan a study that ensures the outcome of data analysis will provide the “correct” or anticipated answer to the research question. Specific statistical procedures may provide the best interpretation of data, but cannot eliminate the need for sound judgments regarding the meaning of the findings. A thorough discussion of alternative ways to interpret the results, of what generalizations may be made based on them, and of methodological limitations and delimitations that could impact the meaning and validity of the results must be presented.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree