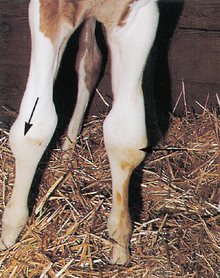

Chapter 3 It is important to recognize the normal events which take place so that the abnormal can be quickly recognized and appropriate corrective action taken. Unfortunately there are wide variations in the normal pattern of delivery and neonatal adaptation, which makes the decision to interfere difficult. The extent of veterinary intervention will often depend heavily on the experience of the owner, handler or groom. More experienced grooms may not need anything like as much support and will also often recognize problems earlier than the less experienced. Furthermore, the value of the foal and any complications during pregnancy will often dictate the role of the veterinary surgeon. The mare will usually then undergo a period of tranquility (lasting up to 20–30 minutes) (Fig. 3.1) during which time the foal shakes its head and gains sternal recumbency with a ‘righting reflex’. Throughout this the mare remains quiet (usually in sternal recumbency) and will often vocalize to the foal. The foal then struggles and moves to the side of the mare. Usually the cord ruptures at this time, either from movement from foal or because the mare stands up. The cord usually ruptures about 6–8 minutes after delivery at a predetermined site (3–5 cm from the umbilicus). Shorter ruptures may have serious consequences including internal hemorrhage. Severe tension on the cord at the umbilicus may also cause serious internal bleeding (though this is very rare. There have been suggestions that premature rupture of the cord may deprive the foal of a significant volume of blood (25–30% of the foal’s blood volume can be lost1). However, studies measuring the haematocrit and haemoglobin in ‘premature cord rupture’ foals, and Doppler flow studies on blood flow within the umbilical vessels, have revealed that blood lost immediately after delivery was not clinically significant.2 Therefore, current opinion is that early (natural) rupture of the cord does not materially affect the adaptive period. 1. Recognition of correct time of interference – minimal interference is desirable. 2. Recognition of the amnion (as opposed to the chorioallantois or even rarely the bladder). 3. Cutting of the amnion is sometimes a desirable safety precaution: the foal’s nose can be uncovered and there is then less risk of asphyxia. However, it is important not to disturb the mare if at all possible while this is done. 4. The foal begins to breathe, taking deep and energy-demanding gasps, and a fast but regular breathing pattern is established. The foal will quickly achieve sternal recumbency with a lifted head; this position is conducive to good pulmonary inflation and function. 5. Cord rupture usually allows slight blood flow. Severe arterial blood loss from the umbilical end of ruptured cord requires immediate attention – clamp with sterile artery forceps or an umbilical clamp (plastic bag clamps are useful). The cord should not be tied with string, etc. 6. Navel treatment is given ideally as soon as the cord has ruptured or at least within 30 minutes of delivery. Recent work suggests that the best results are obtained by the use of chlorhexidine (0.5% solution) and that povidone iodine may not be as effective as was first thought.3 Ensure thorough soaking of the navel but avoid overhandling. Three dip treatments within the first 24 hours will probably be sufficient (see p. 76). 7. Nursing and ingestion of colostrum are essential within 2–4 hours (see p. 14). Intervention is needed if this is not achieved or if the quality of the colostrum is considered to be inadequate (see p. 14). 8. Full hygiene measures are imperative for anyone handling the foal – it is remarkable how few stud personnel have any concept of cleanliness when handling foals and parturient mares. 9. It is advisable to wear gloves and overalls which can be changed frequently on every occasion when dealing with neonatal foals (preferably protective clothing should be changed between different foals). Washing hands and changing overalls frequently also minimizes cross-contamination between mares foaling at the same time. 10. All reasonable hygiene precautions should be in effect at all times including the provision of freshly washed or disposable aprons/gowns for each mare/foal and for each stud. It is best to advise the stud to maintain a stock of these for their own personnel and for visiting vets. Nerve trauma to the brachial plexus (most common, involving some degree of radial nerve paralysis) or lumbosacral plexus occurs most frequently during difficult deliveries. Signs include unilateral or bilateral hypotonia with depressed reflexes. Radial nerve paralysis presents as a foal unable to bear weight on the limb and unable to extend the carpus or digit. Treatment includes anti-inflammatory drugs (care of gastric ulcers) and splinting to allow the foal to bear weight and prevent limb contracture and additional trauma. The prognosis is dependent upon the location and severity of the trauma. Spinal root injury has a worse prognosis than plexus or peripheral nerve injury. Rupture of the common digital extensor tendons (Fig. 3.2) may occur during forced extraction (they can also occur spontaneously; see p. 130). Some facial bruising is almost inevitable during handling and minor episcleral bruising or retinal hemorrhage (Fig. 3.3) is common even in normal foals; these do not usually require treatment. However, it is extremely wise to place such foals in a high risk category so that they are closely monitored for several days for signs of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (see p. 166) because the early signs can be misleading. It is particularly disappointing when extensive treatment (such as internal jaw fixation or skin sutures) is required to correct damage sustained during unsympathetic delivery attempts.

THE FOAL AT DELIVERY

EVENTS FOLLOWING DELIVERY IN THE NORMAL FOAL

SUMMARY OF EVENTS TAKING PLACE DURING THE DELIVERY OF A FOAL

PARTURITION INJURIES IN FOALS

LIMB INJURIES

CRANIAL TRAUMA

THE FOAL AT DELIVERY