1 The Convergence of Human and Animal Medicine

HOW HUMAN AND ANIMAL HEALTH CONVERGE

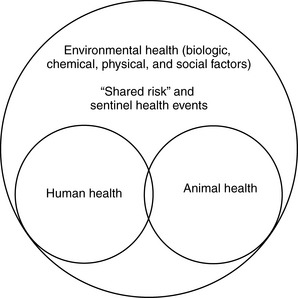

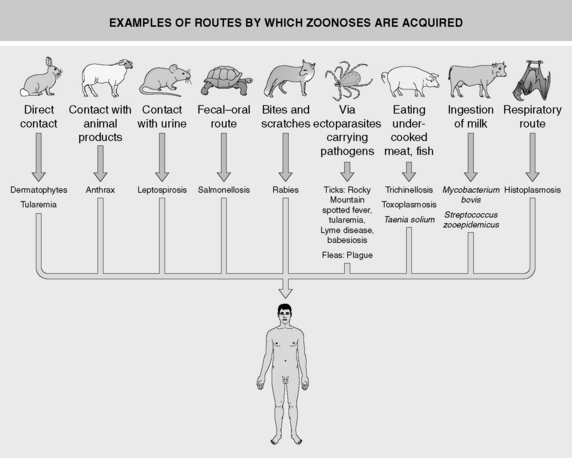

The relationship between human and animal health is becoming increasingly complex and includes biological, chemical, physical, and social factors (Figure 1-1). Both endemic and newly emerging infectious diseases have grabbed headlines and heightened awareness of the role of wild and domestic animal populations in transmitting diseases to human beings. Although the importance of zoonotic disease is not new—approximately 60% of all infectious pathogens of human beings are zoonotic in origin—an even higher percentage of newly emerging diseases over the past 2 decades are zoonoses, many originating from wildlife (Figure 1-2).1 All but one of the bioterrorism agents considered to have the highest potential for use as a weapon of biological warfare are zoonotic pathogens.

Figure 1-2 Examples of routes by which zoonoses are acquired by human beings.

(From Cohen J, Powderly WG: Infectious diseases, ed 2, London, 2003, Mosby Elsevier.)

Pets and Wildlife

More than half of households in the United States own a dog, cat, or both. In addition, millions of exotic wild animals, birds, and reptiles are kept in U.S. households as pets, and the worldwide trade in such animals is accelerating (see Chapter 10).2 Therefore the average patient visiting his or her health care provider is likely to share his or her living space with a pet, and the health of the pet (which may have originated in a wildlife population across the globe) may hold clues to health or disease issues that the patient is experiencing. Furthermore, as suburban developments encroach on wildlife habitat (see Chapter 6), contact with domestic animals, wildlife, and insect vectors may be frequent, allowing pathogens to pass in both directions and bringing human beings into the mix. At the same time, veterinarians in small animal practice have understood for years that pets contribute to improved human mental health and well-being and that the benefits of companion animals usually far exceed the risks of zoonotic disease. A growing body of research now supports the concept of this “human-animal bond phenomenon”; avenues for physician-veterinarian cooperation to maximize these benefits are detailed in Chapter 5.

Food Animals

On a global scale, the growing human population has led to a rapid and unprecedented increase in the numbers and density of animals raised for food production in many parts of the world and the United States (see Chapter 11). The rearing, transportation, marketing, and processing of these animals have significant implications for the occupational health of the human beings working with the animals (Figure 1-3); wildlife that may have contact with such animals; as well as the air, soil, and water quality of agricultural areas (see Chapter 12). The widespread outbreaks of avian influenza among domestic poultry and the threat of the emergence of new strains with pandemic potential are a reminder of these connections. In addition, the increasing reliance on bush meat consumption in many developing countries affects wildlife populations and species diversity and exposes human beings to zoonotic disease threats.3

THE IMPORTANCE OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH TO HUMAN BEINGS AND OTHER ANIMALS

Zoonotic disease represents just one of the ways that the health of companion animals, livestock, and wildlife is inextricably linked with human health. The global environment is rapidly changing, and animals and human beings are exposed to shared environmental health risks. Environmental disasters such as Hurricane Katrina wreak havoc on both human and animal populations. Many zoonotic diseases are emerging as a result of environmental factors, including climate change, deforestation, alterations of wildlife habitat, and other land use change4; human population growth; movement of human beings and animals across borders; and increased production of food animals. The built environment may contribute to a sedentary lifestyle and manifest as an obesity epidemic in both human beings5 and their pets (Figure 1-4). Animals and human beings often share exposure risks from noninfectious disease threats, such as air and water quality problems, pesticides, lead, and carbon monoxide. Just as canaries once warned coal miners of the presence of deadly gases and dead songbirds sent a message to human beings about the risks of pesticides in Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a disease occurrence in an animal can be a “sentinel event” warning human beings of an environmental threat.6 Alternatively, at times a human being has a diagnosed disease that provides information about an environmental risk to animals living nearby. Chapter 4 in this book, as well as the disease-specific chapters, provide many examples of sentinel events and how clinicians and public health professionals can detect them and act on such information to prevent further cases.

SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES AMONG THE TRAINING AND PRACTICE OF HUMAN HEALTH, ANIMAL HEALTH, AND PUBLIC HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

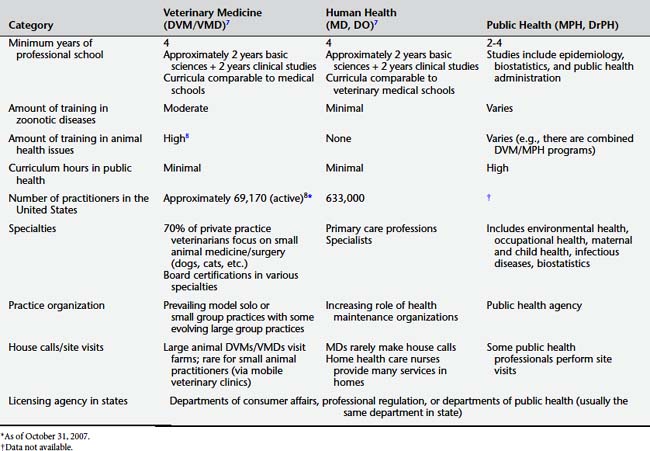

The training and practice patterns of human health care providers, veterinarians, and public health professionals differ in important ways. Table 1-1 outlines some of the key points differentiating the groups.

Role of Veterinarians in Human Health

The expanding role of veterinarians at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, http://www.cdc.gov) reflects a growing trend to create joint teams of veterinarians and human health professionals to deal with human-animal health issues. The team approach has proved synergistic; more rapid and precise evaluations enhance more efficacious control. At the time of this writing, approximately 90 veterinarians work at the CDC.9 The CDC’s National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases (NCZVED) provides leadership, expertise, and service in laboratory and epidemiological science, bioterrorism preparedness, applied research, disease surveillance, and outbreak response for infectious diseases. Its ecological framework includes human beings, animals, and plants interacting in the complex, changing natural environment. Until September 1, 2009, NCZVED was directed and administered by a veterinarian with previous experience as administrator of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS).

From 1953 through 2008, more than 228 veterinarians have completed the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) training at the CDC (Figure 1-5). The EIS represents the U.S’s critical unit for investigating the causes of major epidemics. Over the past 50 years, EIS officers have played crucial roles in combating the root causes of epidemics of major consequence. The EIS has served as a model for similar services in about 25 other countries worldwide.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree