CHAPTER 68 Techniques for Artificial Insemination of Goats

Artificial insemination (AI) involves placement of semen from a male into the reproductive tract of a female by mechanical means rather than by natural mating. A thorough understanding of the various components of an AI program is very important to goat breeders if the herd is to be handled effectively and efficiently. This chapter is designed to provide readers with a foundation to build a sound AI program.

ESTRUS DETECTION AND ARTIFICIAL INSEMINATION

Nothing helps detection of does in heat as much as accurate animal identification such as tags with large numbers or clear brands, and a record-keeping system that indicates when particular animals require observation. Individual doe cards and large calendars are often used to keep simple “heat due” dates.

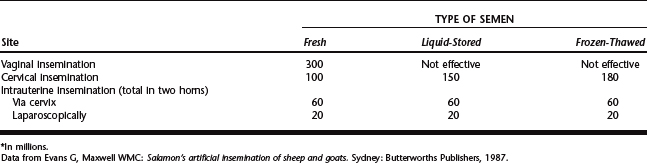

NUMBER OF SPERM PER INSEMINATE

Another important consideration with respect to sperm numbers has to do with the site of semen deposition. Laparoscopic insemination directly into the uterine horns requires fewer sperm than does transcervical insemination into the uterine body. Greater numbers of sperm are required for either cervical or vaginal insemination. Whatever the site of insemination, the number of motile spermatozoa in the inseminate affects fertility. Generally, less fresh extended semen will be needed than frozen-thawed semen. A recommended safe limit for the number of motile spermatozoa is shown in Table 68-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree