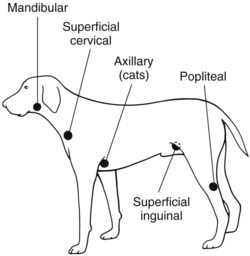

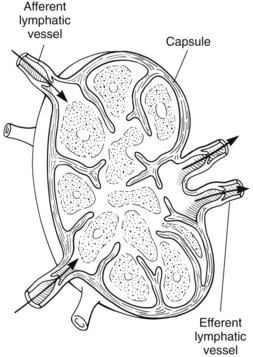

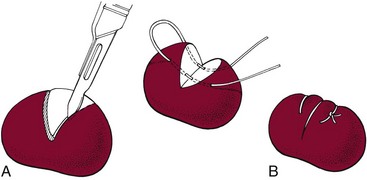

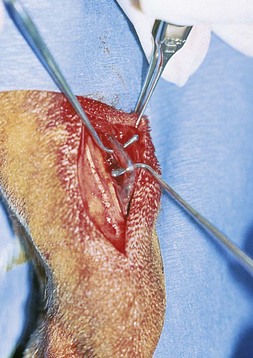

Chapter 24 Surgery of the Lymphatic System The mandibular, superficial cervical (prescapular), superficial inguinal, and popliteal lymph nodes are palpable in most animals (Fig. 24-1). The tonsils may be visualized in the oral cavity, and facial lymph nodes may be found in some normal animals. In dogs, the maxillary, accessory axillary, cervical, femoral, and retropharyngeal lymph nodes usually are palpable only when enlarged; however, the axillary node may be located readily in cats, even when it is only moderately enlarged. Unless the animal is extremely thin or cachectic, sublumbar and mesenteric lymph nodes must be at least moderately enlarged to be detected on rectal or abdominal palpation. The texture of the enlarged node and sensitivity to pressure or manipulation should be noted. Acute enlargement (i.e., suppurative lymphadenitis) can be associated with pain, but lymphoid neoplasia usually causes painless enlargement. Metastatic neoplasia and fungal infections sometimes cause nodes to become fixed to surrounding tissue. Clinical signs may result from lymphadenomegaly (e.g., coughing caused by tracheal compression by enlarged hilar lymph nodes, constipation resulting from sublumbar lymphadenopathy). Lymphangiomas are rare, benign neoplasms originating from lymphatic capillaries. They are believed to be developmental anomalies associated with failure of primitive lymphatic sacs to establish venous communication. These endothelial sprouts continue to grow, infiltrate surrounding tissue, cause pressure and subsequent necrosis, and form cystic structures. They typically manifest as large, fluctuant swellings that are noticed incidentally or because of interference with normal structures as a result of expansive growth. They have been identified arising from subcutaneous tissue, the nasopharynx, and the retroperitoneal space of dogs and in the liver and the mediastinum in cats. Affected dogs usually are middle-aged or older; however, lymphangiomas may occur in young dogs. In a recent study of vascular tumors in 420 dogs, only one lymphangioma was observed (Gamlem et al, 2008). Treatment for lymphangioma consists of complete surgical excision or marsupialization. A lymphangiomatous mass arising from the right palatine tonsil was removed without complications or evidence of recurrence in an 8-year-old female dog (Miller et al, 2008). Lymphangiosarcomas (Fig. 24-2) are malignant tumors that arise from lymphatic capillaries. They are locally aggressive, and metastasis to regional lymph nodes, lungs, spleen, kidneys, and bone marrow has been reported. Even without metastasis, the local invasiveness of this tumor often necessitates euthanasia. Surgical resection may be considered; however, cure is unlikely. These tumors have been reported most often in medium- to large-breed dogs. They may occur in young dogs; however, most affected dogs are middle-aged or older. Diagnosis may be made by histopathology, electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, tissue culture, and/or endothelial expression of glycoconjugates (Williams, 2005). Histologically, lymphangiomas and lymphangiosarcomas are composed of vascular spaces lined by endothelial cells and focal lymphoid aggregates divided by connective tissue stroma. Unlike hemangiomas, the cystic spaces of these tumors are not filled with blood. Perioperative antibiotics are seldom indicated in animals undergoing lymph node biopsy or removal. Lymph nodes are bean-shaped structures with a convex surface and a small flat or concave hilus (Fig. 24-3). They usually are found encased in fat at flexor angles or joints, in the mediastinum and mesentery, and in the angle formed by the origin of larger blood vessels. Ultrasound is useful in detecting mesenteric, gastric, and hepatic lymphadenomegaly. Parameters that can be evaluated using ultrasound include lymph node size and margins, echotexture and echogenicity, presence and distribution of vascular flow, vascular flow indices, and acoustic transmission. The most diagnostically helpful parameters include the short/long axis ratio of the lymph node, the pattern of distribution of the blood vessels within the lymph node, and to some extent the resistive and pulsatility indices (Nyman and O’Brien, 2007). Incisional (wedge) biopsy of lymph nodes is indicated when lymphadenectomy may be difficult because of a node’s size or location (e.g., nodes that are located close to major vessels or nerves). Use a No. 15 scalpel blade to remove a wedge-shaped section of the parenchyma (Fig. 24-4, A), and place the sample in a buffered formalin solution. To provide hemostasis, place a horizontal mattress suture of absorbable suture material (e.g., 3-0 chromic catgut) to close the incision (Fig. 24-4, B). Gamlem, H, Nordstoga, K, Arnesen, K. Canine vascular neoplasia—a population-based clinicopathologic study of 439 tumours and tumour-like lesions in 420 dogs. APMIS Suppl. 2008;125:41. Miller, AD, Alcaraz, A, McDonough, SP. Tonsillar lymphangiomatous polyp in a dog. J Comp Pathol. 2008;138:215. Nyman, HT, O’Brien, RT. The sonographic evaluation of lymph nodes. Clin Tech Small Animal Pract. 2007;22:128. Williams, JH. Lymphangiosarcoma of dogs: a review. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2005;76:127. Specific Diseases Lymphedema may be a result of a primary defect in the lymphatic system or may occur secondary to other diseases or surgical procedures. Distinguishing between primary and secondary lymphedema often is difficult. Lymph node obstruction, although more commonly associated with secondary lymphedema, has been associated with primary lymphedema. Many of the dogs reported with primary lymphedema have had small or absent lymph nodes. Perhaps the initial defect in some dogs with lymphedema is fibrosis of the lymph nodes, which leads to secondary obstructive changes in the lymphatic vessels. As the vessels dilate, they lose contractility, and the lymphatic valves become permanently nonfunctional. Secondary lymphedema may be caused by conditions that increase the rate of interstitial fluid formation as a result of altered capillary permeability (e.g., trauma, heat, irradiation, infection). Venous congestion (i.e., because of heart failure) may also cause lymphedema by reducing fluid resorption. Secondary lymphedema can result from neoplasia or infiltration of lymph nodes by filaria, such as Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia timori, and from lymphoproliferative disorders. Secondary malignant lymphedema was recently reported after mastectomy in two dogs (Kang et al, 2007). Both dogs had large edematous lesions associated with lameness in the right hindlimb following surgery. Obstruction of lymph flow in the lymphatics of the right hindlimbs was shown with lymphangiography in one dog and lymphoscintigraphy in the other dog. The diagnosis of lymphedema usually is made on the basis of clinical signs (Fig. 24-5). The limb generally is not excessively warm or cool. Although the condition often is bilateral, the degree of swelling frequently is greater in one limb. Occasionally, swelling may be precipitated by minor trauma or superficial skin infection. Fibrosis occurs as the edema becomes chronic, and the edema tends to progressively pit less until pitting is absent. With chronic edema, massage and rest do not appreciably reduce the size of the limb. The benzopyrones are a group of drugs that have been used to successfully treat experimental lymphedema in dogs and spontaneous lymphedema in human beings. All the drugs in this group appear to reduce high-protein edema. Their main action appears to be stimulation of macrophages, which promotes proteolysis. Protein fragments can then be reabsorbed into the blood. These drugs are active orally and topically, are inexpensive, and are relatively free of side effects. Included in this category of drugs are coumarin (5,6 benzo-[a]-pyrone), O-(β-hydroxy-ethyl)-rutosides, diosmin, and rutin. Recommended dosages for human beings are 440 mg/day of coumarin and 3 g/day of rutosides, diosmin, and rutin (Box 24-1). Although these drugs (e.g., rutin) are being investigated for spontaneous lymphedema in dogs, their efficacy currently is uncertain. The classic diagnostic tool has been direct lymphography (lymphangiography) (see p. 691 for a description of the technique). Oil-based contrast media are contraindicated in patients with primary lymphedema because the high volume of contrast medium necessary to visualize the lymphatics and the propensity for extravasation may further damage existing lymphatics. Lymphoscintigraphy, an alternative method of imaging the peripheral lymphatics, involves intradermal injection of high molecular weight, radiolabeled colloids. A gamma camera is used to obtain images of the affected limb over time to observe the progression of radioactivity through the lymphatics. Primary lymphedema typically shows slow absorption of the radiopharmaceutical, reduced visualization of lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes, and no interstitial activity. Secondary lymphedema typically shows poorly visualized primary lymph vessels and dilated secondary lymph vessels. Significant interstitial activity is also noted. Except for amputation, no current surgical treatment offers a cure for lymphedema. Numerous therapies have been described in human patients, including lymphangioplasty, bridging procedures, lymphaticovenous shunts, omental transposition, superficial to deep anastomosis, and excision (with or without skin grafting). These techniques have not been adequately evaluated in dogs with spontaneous lymphedema. Lymphangiography rarely provides information that helps in management of animals with spontaneous lymphedema, but it occasionally defines the underlying lymphatic abnormality (i.e., hypoplasia, aplasia, or hyperplasia of lymphatics). It is a tool that must be correlated with other historical and physical findings. Biopsy samples of affected tissues should be submitted because lymphangiosarcoma, a highly malignant neoplasm, has been reported to occur in human beings with long-standing lymphedema. The technique for lymphangiography is described on p. 691. The lymphatic system of the extremities can be divided into two parts: superficial and deep (i.e., muscular) lymphatics. The superficial system appears to be the one most commonly involved in lymphedema. This is the system of lymphatics observed during pedal lymphangiography (Fig. 24-6). These lymphatics empty into a valved group of vessels found at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Lymph then drains into afferent lymphatics in the subcutaneous fat. The superficial lymphatics of the pelvic limb consist of a larger medial group and a smaller lateral group. Lymphatics follow the branches of the medial saphenous vein and drain into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Efferent lymphatics from the lymph nodes drain into the larger lymphatic ducts. The deeper lymphatics drain the fascial planes surrounding skeletal muscles (lymphatics are not found in skeletal muscle bundles), joints, and synovium. Deep lymphatic collector vessels accompany the main blood vessels of the extremities. Controversy continues as to whether the two lymphatic systems (superficial and deep) communicate; however, communications usually appear to be a result of a lymphatic pathologic condition or a response to abnormal lymph flow. The lumbar lymph trunks receive vessels from the pelvic limbs, the abdominal lymph nodes, and the intestines before uniting to form the cisterna chyli. Make a 5-cm skin incision over the mid-dorsomedial metatarsal region. Use sharp and blunt dissection until a blue-stained, superficial metatarsal lymphatic vessel is identified (Fig. 24-7). Meticulously dissect the lymphatic free from surrounding tissue with fine, blunt dissection probes, and cannulate the lymphatic using a lymph duct cannulator or a 27 or 30 gauge over-the-needle catheter. Inject a small amount of sterile saline into the catheter or cannulator to verify patency. Then manually infuse an aqueous-based radiographic contrast agent into the lymphatic vessel. Take radiographs immediately after the injection (Fig. 24-8); additional radiographs may be taken, depending on the rate of lymphatic transport of the contrast agent, which varies from patient to patient. Upon completion of the lymphangiogram, withdraw the cannulator, ligate the lymphatic vessel, and close the incision in a routine fashion.

Surgery of the Hemolymphatic System

General Principles and Techniques

Preoperative Management

Antibiotics

Surgical Anatomy

Diagnostic Imaging

Surgical Technique

Incisional Biopsy

References

Lymphedema

General Considerations and Clinically Relevant Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Physical Examination Findings

Medical Management

Lymphography and Lymphoscintigraphy

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Anatomy

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgery of the Hemolymphatic System