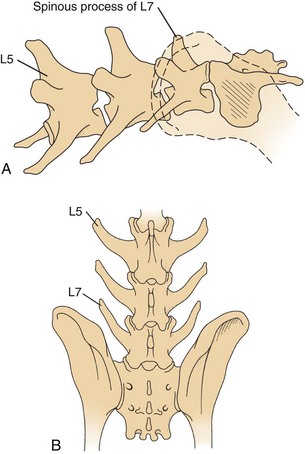

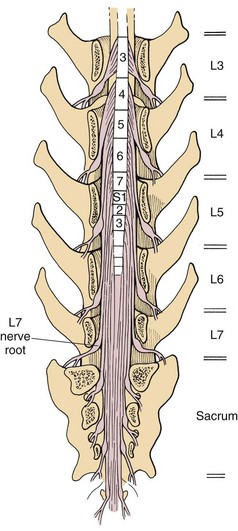

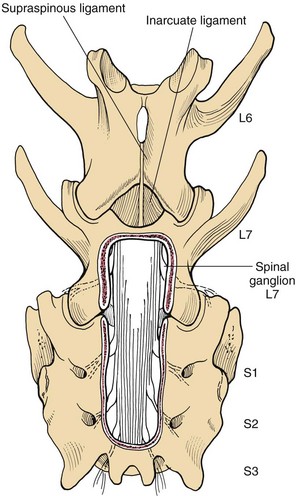

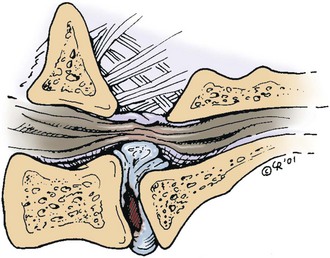

Chapter 42 Specifics of preoperative management depend largely on the disease process. In cases of degenerative lumbosacral stenosis, most patients will benefit from analgesic drugs prior to scheduling for surgery. There are multiple options for oral analgesic drug therapy for these patients, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tramadol, and either gabapentin or pregabalin (see p. 1440). Pregabalin appears to be effective in relieving pain associated with nerve root compression in dogs with degenerative lumbosacral stenosis. In the author’s opinion, there is no advantage of corticosteroids over NSAIDs in patients with cauda equina lesions, and there are potential disadvantages of corticosteroid use. Patients with radiographic evidence of diskospondylitis (see p. 1558) should be treated with appropriate antibiotic regimens (e.g., oral cefadroxil, 22 mg/kg every 8 hours or clindamycin, 11 mg/kg every 8 hours). The L7/S1 disk space is the most common site for diskospondylitis, and some dogs will have this infectious process as well as degenerative lumbosacral stenosis. It is prudent to control the infection before considering surgical decompression; in some cases, treatment of the infectious disease resolves clinical signs of disease and surgery is not needed. In traumatic fractures/luxations of the lumbosacral area, treatment is similar to that described for trauma to other regions of the spine (see pp. 1505 and 1525). These patients need to be stabilized from a cardiovascular standpoint and evaluated for injury to other organ systems. Additionally, these patients need to be kept as immobile as possible to avoid further damage to the nerve roots of the cauda equina. Anesthetic management of the patient with a cauda equina lesion is similar to that described for patients with other spinal surgical disorders (see pp. 1468 to 1508). The lumbosacral junction has many features in common with other regions of the lumbar spine (see p. 1509), but there are several unique features (Fig. 42-1). The dorsal spinous process of L7 is considerably shorter than that of L6 and the intervertebral foramen of the lumbosacral junction is dorsoventrally flattened in comparison with cranial lumbar vertebrae. The lateral aspects of this foramen have been referred to as the lateral recesses and contain the L7 nerve root as it runs caudally toward the L7/S1 intervertebral foramen. The sacrum is composed of three fused vertebrae, and the fused dorsal spinous processes form a median sacral crest. The dorsal lamina of the sacrum is considerably thinner than the L7 dorsal lamina, and in small dogs and cats it may not have a visually distinguishable inner medullary cancellous bone layer. The prominent ilial wings of the pelvis project dorsally over the dorsal aspect of the sacrum and cranially to the level of the L6/L7 disk space. Clinically relevant soft tissue structures in the lumbosacral junction include the termination of the spinal cord and the cauda equina nerve roots as well as supportive joint and ligamentous tissues and blood vessels. In medium to large-breed dogs, the spinal cord ends (conus medullaris) at the L6 or L7 vertebral level (Fig. 42-2). In small dogs and cats, the spinal cord terminates more caudally, around the S1 vertebral level. The filium terminale is a meningeal extension beyond the conus medullaris that attaches to the caudal (coccygeal vertebrae). As in the rest of the vertebral canal, paired venous sinuses (internal vertebral venous plexuses) are located on the floor of the canal. Radicular vessels (artery and vein) travel through the L7/S1 intervertebral foramina along with the L7 nerve root. Small blood vessels also exit the dorsal sacral foramina-these are usually cauterized at surgery or occluded with bone wax. Supportive connective tissues at the lumbosacral junction include the intervertebral disk and dorsal longitudinal ligaments ventrally, the articular process (facet) joint capsules laterally, and the ligamentum flavum (interarcuate ligament) and interspinous ligaments dorsally. Dorsal laminectomy is used to access the cauda equina, with or without removal of articular process tissue (foraminotomy or facetectomy). Crucial to the performance of a dorsal laminectomy in this region of the spine is proper positioning. The patient should be positioned in a manner that opens the L7/S1 space. The pelvic limbs are flexed, and positioned along the patient’s abdomen (Fig. 42-3). Position the patient in sternal recumbency with the pelvic limbs pulled cranially as shown in Fig. 42-3. Maintain this position with sandbags, towels, a deflated air cushion, or a V-trough. Using the iliac crests and L6 dorsal spinous process as landmarks, create a midline incision from the dorsal spinous process of L5 to the end of the sacral crest (base of the tail). Sharply incise through subcutaneous tissue and fat to reach the thick lumbodorsal fascia. Incise this fascial layer on midline and around the dorsal spinous processes of interest with a No. 11 blade, Mayo scissors, or a combination of the two. Elevate the multifidus lumborum (cranially) and sacrocaudalis dorsalis medialis (caudally) muscles from the dorsal spinous processes and median sacral crest using either Freer periosteal elevators (small dogs and cats) or Army-Navy osteotomes (large dogs). Continue this periosteal elevation to expose the dorsal lamina of L7 and the sacrum. Exposure of the L7/S1 junction is facilitated by also exposing L6/L7. Fully expose the articular processes of L7/S1 laterally to the level of the medial aspect of the ilium on each side. Place Gelpi retractors cranially and caudally. Sharply excise the interarcuate ligament between L7 and S1. Identify the interarcuate space of L7/S1 and carefully excise ligamentum flavum tissue with a No. 11 blade and a nontoothed Bishop Harmon forceps so that the bone edges of caudal L7 and cranial S1 are visualized. Remove the dorsal spinous process of L7 and the cranial half of the median sacral crest with a bone cutter and/or rongeur. Use a high-speed air drill to create the dorsal laminectomy defect, drilling through outer cortical and inner cancellous bone to reach the inner cortical layer. The lateral aspects of the L7 dorsal lamina are thickest, and the dorsal lamina of the sacrum is considerably thinner than that of L7. Once the inner cortical bone is soft enough, remove it with fine-tipped Lempert rongeurs and/or flake it off with the spatula end of a Gross ear hook and spoon. Remove any remaining periosteum and/or interarcuate ligament (ligamentum flavum) and overlying epidural fat to expose the cauda equina (Fig. 42-4). In some chronic cases of degenerative lumbosacral stenosis, the ligamentum flavum and/or endosteum may be adhered to the nerve roots; in this case, carefully dissect the connective tissue off the nerve roots with a No. 11 blade. Using a probe (e.g., Gross ear hook and spoon), feel under the edges of the laminectomy defect, especially laterally and in the region of each intervertebral foramen. If compression of the L7 nerve root is still apparent after dorsal laminectomy and removal of compressive annulus tissue, perform a facetectomy or foraminotomy. The nerve roots of the cauda equina are more resistant to injury compared with spinal cord parenchyma and respond to injury similar to the response of peripheral nerves. Nerve injury is typically classified according to severity. From least severe to most severe, nerve injury is classified as class I (neurapraxia), class II (axonotmesis), and class III (neurotmesis) (Table 42-1). Class I injury or neuropraxia refers to a transient lack of nerve function, with little or no structural damage to the axons or their supportive connective tissue structures. This temporary dysfunction may be due to ischemia (no structural damage) and/or mild paranodal demyelination. The degree of motor and proprioceptive dysfunction is variable, but nociceptive function is preserved for the most part (large-diameter axons are preferentially affected). Spontaneous recovery is expected within days to a month, depending on the degree of demyelination. Neurogenic muscle atrophy is unlikely, as the axons are structurally intact. With class II injury (axonotmesis), some or all of the axons of the nerve are disrupted structurally, but the connective tissue support (e.g., Schwann cell basal lamina, endoneurium) remains intact. These axons can regrow along the connective tissue scaffold. Substantial motor, proprioceptive, and nociceptive dysfunction is expected, the extent of which depends on the number of axons damaged. Neurogenic muscle atrophy is likely with this class of injury. Class III injury or neurotmesis denotes complete severance of the axons of the nerve, as well as the connective tissue support. These axons will not regrow (no guiding scaffold) without surgical intervention. Complete motor, proprioceptive, and nociceptive (i.e., no pain perception) dysfunction occurs with this class of injury. Neurogenic muscle atrophy is to be expected. A severe class II injury may be clinically indistinguishable from a class III injury. In addition to the extent of nerve injury, the length of nerve required to regenerate affects prognosis. Axons grow at a rate of 1 to 4 mm per day. In people with nerve injuries, muscle motor end-plate degeneration tends to occur if the damaged nerve does not reestablish contact with the target muscle within 18 months. Therefore, proximal nerve injuries have more guarded prognoses than distal injuries, even if axonal regeneration occurs. Causes and Characteristics of Nerve Injuries Suture material and special instruments for cauda equina surgery are the same as those used for thoracolumbar spinal surgery (see pp. 1513 and 1518). Specific Diseases The pathogenesis of DLS involves type II degeneration and subsequent protrusion of the L7-S1 intervertebral disk into the vertebral canal (Fig. 42-5). There are often other degenerative changes at the lumbosacral junction, indicative of chronic instability. Ventral spondylosis is often appreciated at the lumbosacral junction in these patients, but by itself, this radiographic finding has little clinical significance. Some of the degenerative changes, other than disk protrusion, that may lead to compression of the cauda equina include collapse of the intervertebral disk space at L7/S1 and subluxation of the L7/S1 articular facets; the craniodorsal aspect of the sacrum may become displaced ventral to the caudodorsal aspect of the L7 vertebra; hypertrophy and folding inward (ventrally) of the interarcuate ligament (ligamentum flavum) located between the dorsal laminae of L7 and S1 may occur; and hypertrophy of soft tissue structures (e.g., joint capsule) as well as osteophyte formation associated with the L7/S1 articular processes (facets) may be observed.

Surgery of the Cauda Equina

General Principles and Techniques

General Considerations

Preoperative Management

Anesthesia

Surgical Anatomy

Surgical Technique

Dorsal Laminectomy

Healing of the Cauda Equina

![]() Table 42-1

Table 42-1

Nerve Injury Classification

Causes

Characteristics

Class I (Neurapraxia)

Ischemia (no structural damage) and/or mild paranodal demyelination

Transient lack of nerve function

Little to no structural damage to axons

Variable motor and proprioceptive dysfunction

Nociceptive function is generally preserved

Spontaneous recovery within days to a month

Class II (Axonotmesis)

Mainly seen in crush injury

Structural disruption of axons

Connective tissue support remains intact

Axons may regrow along connective tissue scaffold

Substantial motor, proprioceptive, and nociceptive dysfunction

Neurogenic muscle atrophy

Class III (Neurotmesis)

Occurs with severe contusion, stretch, or laceration

Complete severance of axons of the nerve and connective tissue

Axons will not regrow without surgical intervention

Complete motor, proprioceptive, and nociceptive dysfunction

Neurogenic muscle atrophy

Suture Materials and Special Instruments

Degenerative Lumbosacral Stenosis

General Considerations and Clinically Relevant Pathophysiology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgery of the Cauda Equina