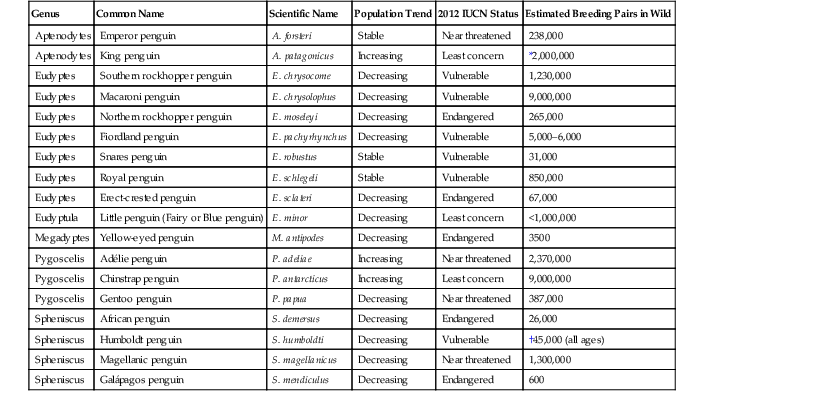

Roberta S. Wallace Penguins are flightless pelagic birds that are widely distributed along the coastal areas of the southern hemisphere, from cold tolerant species inhabiting Antarctica and the subantarctic areas, to temperate species found near the equator.37 Currently, 6 genera and 18 recognized species (Table 10-1) exist, with the rockhopper penguin (Eudyptes chrysocome) recently being split into two distinct species on the basis of morphologic, vocal, and genetic distinctions: the northern rockhopper penguin (Eudyptes moseleyi) and the southern rockhopper penguin (Eudyptes chrysocome).17 Penguins are long lived, with captive individuals frequently living to be 25 to 30 years of age. Age of sexual maturity varies among species but usually occurs around 3 to 5 years of age. Penguins are generally monogamous. Some species mate with one partner each season but change partners in successive breeding seasons, whereas other species form strong pair bonds that last for the life of the individuals. Occasionally, extra-mate pairing occurs. Males and females share the responsibility for incubation and chick rearing. Most species have a clutch of two eggs and use a variety of nest types: under rocks or bushes, in small cavities, or in shallow scrapes. Some build nests out of stones or dig deep burrows. Incubation generally lasts 37 to 45 days. Aptenodyptes is the exception, laying only one egg per clutch and incubating the egg on its feet for 62 to 67 days.37 TABLE 10-1 Status of Wild Penguin Species Populations * International Penguin Conservation Working Group (www.penguins.cr). † Wallace, unpublished data. From International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2012: Red List of Threatened Species Version 2012.2: www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed December 24, 2012. Penguin species have a very similar body shape that allows for efficient swimming, diving, and porpoising but vary in height and weight. The little blue penguin is the smallest, standing 40 centimeters (cm) tall and weighing about 1 kilogram (kg), whereas the emperor penguin is the largest and may reach a height of 130 cm and weigh up to 38 kg. Despite the size differences among species, all penguins share several unique anatomic features. 6. Daily activities of penguins have both aquatic and terrestrial components. The visual system has anatomic features that allow penguins to have normal sight in either environment. Although the corneal shape is flatter than in mammals, the ultrastructure is similar.26 The nictitating membrane is transparent to allow normal vision while providing protection to the cornea when the penguin is under water. When performing ocular surgery, the nictitating membrane must be identified and retracted to avoid accidental incision. 7. Salt glands in the orbital region handle the excess salt in a marine environment. The glands will atrophy in captive penguins maintained in a fresh water environment unless supplemental salt is provided. However, studies have shown that atrophied glands will become functional rapidly if exposed to a saline environment.20 The use of flipper bands in the wild is controversial.2,15 However, most institutions successfully use flipper bands on captive penguins. Color cable ties and metal or silicone flipper bands may be used. Bands should be tightened to the point where a finger may be slipped between the band and the flipper. As cable ties may continue to tighten after application, the fastener should be glued so that it does not slip and impede blood circulation to the flipper. During molt, flippers swell, potentially restricting circulation. Band tightness must be monitored and bands replaced with looser bands, if needed. Small metal rings may be placed in the interdigital webbing of the foot. Microchips may be placed subcutaneously in the loose skin of the back of the neck, on top of the head, or in the fleshy part of the foot in the front of the tarsus. Chicks weighing as little as 500 grams (g) may be microchipped. For smaller collections, identification of adults may be done on the basis of photographs of spot patterns of the breast feathers after molt into adult plumage.24 Penguin species are only subtly dimorphic, males generally being slightly larger with bigger and thicker bills, but overlap in size exists between sexes. Although research on morphometrics has been published, it is unreliable for captive Humboldt penguins and thus might be expected to be unreliable for other penguin species. DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) sexing from feather, blood, or egg membranes is highly reliable and is the recommended method for sexing penguins.24 To successfully manage penguins in captivity, exhibits must be designed to meet the physical, behavioral, and psychological needs of the species. As colony birds, penguins should not be housed alone, and the AZA Penguin Taxonomic Advisory Group (TAG) recommends a minimum of 10 birds. Air and water quality, lighting, and type of substrate must be considered for optimal health as well as protection from land and air predators. The various penguin species have widely differing environmental requirements, and it must be ensured that in a mixed species exhibit, penguins with similar requirements are housed together. Indoor exhibits are generally preferred to facilitate control of air and water temperatures for the various species, decrease exposure to disease vectors, and provide protection from predators. Aptenodyptes, Pygoscelis, Eudyptes, and Megadyptes species are best kept indoors under refrigerated conditions (<9° C). Temperate climate species are often exhibited outdoors and may tolerate temperature ranges from freezing to 30° C. In cold climates, pools should be prevented from freezing, and penguins should have access to shelters with supplemental heat. Misters may be used during warm weather to aid in cooling the birds. An indoor area with climate control capability should be available for protection from extreme heat and humidity and for nesting. Mosquitoes are the vectors for several diseases in penguins (see list below); therefore, mosquito control is paramount for penguins housed outdoors. This includes removing standing water on a weekly basis; applying larvicide to standing water that cannot be removed, including any drains in the penguins’ indoor and outdoor enclosures; and minimizing foliage near animal exhibits. Exposure to mosquitoes may be reduced by bringing the penguins indoors during peak mosquito hours (dusk to dawn), ensuring that door sweeps and screens are in good condition, placing screens over intake fans, and providing fans, wherever possible, to keep the air moving to discourage mosquitoes.24 The AZA Penguin TAG recommends minimum land and water surface areas for exhibition and holding. Additional space should be provided to allow for a full range of species-appropriate behaviors, including nesting (species other than Aptenodytes). For king and emperor penguins, the minimum land and water surface areas for exhibit and holding are 18 square feet for the first six birds and 9 square feet for each additional bird, with a minimum pool depth of 4 feet. For all other species of penguins, the recommendations are 8 square feet for the first six birds, 4 square feet for each additional bird, and a minimum pool depth of 2 feet. Ideally, larger water areas should be provided to encourage swimming to help prevent obesity and pododermatitis. A separate holding area should be provided for birds with behavioral problems or noncontagious health problems that require separation from the flock. Quarantine facilities with separate air and water systems should be available for newly acquired birds or birds with infectious diseases. Water may be either fresh water or salt water, and recent studies show that salt supplementation is not needed for penguins in fresh water exhibits. Water cleanliness and clarity may be maintained with the use of sand and gravel filters, judicious addition of chlorine to keep coliform counts to a minimum, and surface skimmers to remove excess fish oil and debris from the surface of the water. Lighting indoor exhibits should mimic the natural light cycle with gradual increasing and decreasing of daylight hours. Inappropriate lighting may lead to poor molt cycles and decreased reproductive success.24 Spheniscid species enjoy climbing, so exhibits designed to allow climbing provide enrichment. In the wild, penguins feed on pelagic schooling fish species, squid, and crustaceans (mostly euphasid species). Food consumed varies with availability and season. In captivity, the type of prey items fed by a given institution is often limited and dictated by cost and availability from commercial fisheries. Feeding several different types of whole prey is recommended to provide a complete nutrient profile and so that the birds do not “imprint” on one item to the exclusion of others. In most cases, the prey items are frozen. Fish should be individually quick frozen (IQF) instead of in large blocks, stored at −18° to −30° C, and used within 4 to 6 months to ensure optimal nutritional quality. Institutions should consider whether the food items used are being harvested in an ecologically sustainable fashion.10 If appropriate species of prey are unavailable or the condition of the fish is less than ideal, three types of a nutritionally complete powder (reconstituted into a gel) are commercially available as substitutes for low-fat fish, high-fat fish, or squid and crustacean diets. The size of the fish must be appropriate for the species. If an item must be cut because it is too large, all portions should be fed to ensure ingestion of the entire nutrient supply of the item. To prevent bacterial growth, food should be thawed in a refrigerator in clean containers, then kept refrigerated or on ice until the time of feeding. Using running water for thawing may wash away many of the water-soluble nutrients, but in some institutions, the fish is quickly rinsed in cold water just prior to feeding to remove any surface contaminants. Extensive vitamin supplementation is not needed if penguins are fed good-quality whole-food items thawed appropriately. Recommendations are limited to vitamin E at 100 international units per kilogram (IU/kg) and thiamine at 25 to 30 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg) of diet fed on a wet weight basis. Supplements should be added to the fish immediately before feeding to prevent breakdown by the enzymes and oxidants in the fish. Salt supplementation is not needed.10 Most institutions hand-feed individual penguins, especially if they are receiving medication or vitamin supplements. Complete hand-feeding may cause penguins to become lazy and develop poor swimming habits; therefore, some pool feeding is recommended, but feeding must be observed to ensure that all individuals are eating enough. Penguins may consume up to 20% of their body weight daily, with increased consumption during the few weeks prior to molt, and during chick rearing. Consumption usually decreases drastically during molt with frequent skipped feedings. Penguins may gain more than 25% of their body weight prior to molt and then rapidly return to premolt weight or slightly below by the end of molt.37

Sphenisciformes (Penguins)

Biology

Genus

Common Name

Scientific Name

Population Trend

2012 IUCN Status

Estimated Breeding Pairs in Wild

Aptenodytes

Emperor penguin

A. forsteri

Stable

Near threatened

238,000

Aptenodytes

King penguin

A. patagonicus

Increasing

Least concern

*2,000,000

Eudyptes

Southern rockhopper penguin

E. chrysocome

Decreasing

Vulnerable

1,230,000

Eudyptes

Macaroni penguin

E. chrysolophus

Decreasing

Vulnerable

9,000,000

Eudyptes

Northern rockhopper penguin

E. moseleyi

Decreasing

Endangered

265,000

Eudyptes

Fiordland penguin

E. pachyrhynchus

Decreasing

Vulnerable

5,000–6,000

Eudyptes

Snares penguin

E. robustus

Stable

Vulnerable

31,000

Eudyptes

Royal penguin

E. schlegeli

Stable

Vulnerable

850,000

Eudyptes

Erect-crested penguin

E. sclateri

Decreasing

Endangered

67,000

Eudyptula

Little penguin (Fairy or Blue penguin)

E. minor

Decreasing

Least concern

<1,000,000

Megadyptes

Yellow-eyed penguin

M. antipodes

Decreasing

Endangered

3500

Pygoscelis

Adélie penguin

P. adeliae

Increasing

Near threatened

2,370,000

Pygoscelis

Chinstrap penguin

P. antarcticus

Increasing

Least concern

9,000,000

Pygoscelis

Gentoo penguin

P. papua

Decreasing

Near threatened

387,000

Spheniscus

African penguin

S. demersus

Decreasing

Endangered

26,000

Spheniscus

Humboldt penguin

S. humboldti

Decreasing

Vulnerable

†45,000 (all ages)

Spheniscus

Magellanic penguin

S. magellanicus

Decreasing

Near threatened

1,300,000

Spheniscus

Galápagos penguin

S. mendiculus

Decreasing

Endangered

600

Unique Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

Identification Methods

Sexing

Special Housing Requirements

Feeding and Nutrition

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree