CHAPTER 117 Semen Collection and Artificial Insemination in Llamas and Alpacas

Artificial insemination (AI) with frozen semen is one of the most important reproductive technologies in farm animal production and is used worldwide in several species of domestic ruminants including cattle, sheep, and goats. The economic benefit of AI has been well documented as a means of enhancing the genetic potential within a herd. The use of AI in South American camelids would provide important opportunities for (1) genetic improvement of the domestic species (llama and alpaca), (2) preservation of threatened wild species (vicuna and guanaco), and (3) international movement of genetic material. However, difficulties with semen collection, dilution, and cryopreservation have limited the development and use of AI in camelid species.

METHODS OF SEMEN COLLECTION

Several methods have been used to collect semen from camelids, with variable results. It is difficult to collect and handle semen from llamas and alpacas because of the mating posture, duration of copulation (varying from 12 to 50 minutes1), intrauterine deposition of semen, and the viscous nature of the ejaculate. Attempts at semen collection in camelids have included the use of condoms or intravaginal sacs, vaginal sponges, electroejaculation, postcoital vaginal aspiration, and fistulation of the penile urethra. The use of intravaginal sacs was first described by Mogrovego,2 but the procedure was cumbersome, it hindered normal copulation, and it was associated with vaginal injury ostensibly when intrauterine intromission was attempted. An alternative approach was to insert sterile sponges into the cranial vagina, but again, semen collection was poor and the semen that was collected was of low quality and highly contaminated.3

In early reports4,5 electroejaculation was attempted in alpacas and involved the insertion of an electroejaculator probe into the rectum and applying gradually increasing electrical stimulation in a periodic fashion (i.e., 4 to 6 seconds of stimulation followed by 4 to 6 seconds of rest). From 1.1 to 1.8 ml of semen was collected but sperm concentration (range: 1000 to 255,000 spermatozoa/mm3) and quality were extremely variable, and contamination with urine was common.

The development of an artificial vagina (AV), similar to that used in sheep, was first reported by Sumar and Leyva.6 The AV included a coil spring to simulate the cervix and was mounted inside a dummy that the males were trained to mount. However, the lack of adequate heating equipment required repeated refilling of the hot water chamber to maintain a stable AV temperature during prolonged copulation. The technique was improved with the use of an electric heating pad wrapped around the AV.7 Collection of semen by an AV mounted inside a dummy is more reliable than other methods and provides a more physiologic sample of semen6 (Fig. 117-1). An alternative to a dummy mount is the use of a receptive female; the penis of the male can be directed into an AV during the mount.7,8 The disadvantage of semen collection with an AV is that the males must be trained to serve the AV; perhaps because ejaculation occurs over such a long time, male llamas and alpacas do not serve an AV as readily as bulls and rams. However, consistent results can be obtained once the males become accustomed to the AV with a dummy or live mount.

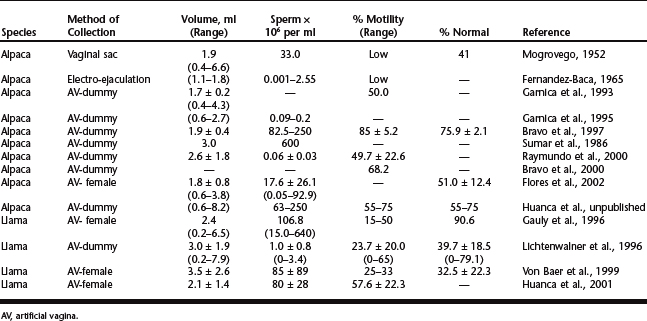

The results of semen collection by electroejaculation or with the use of an artificial vagina are summarized in Table 117-1. Note the extreme variability in semen volume and concentration. Results of llama studies appear less variable; the average volume of semen per collection was about 2 to 3 ml and the concentration of spermatozoa was about 1 × 106 to 80 × 106 sperm/ml.8–10

SEMEN HANDLING—FRESH AND FROZEN

Effective use of AI requires the dilution and storage of semen, but difficulties in semen collection and handling in llamas and alpacas have been an impediment. The semen of alpacas and llamas is highly viscous13,18 and makes assessment of sperm concentration, morphology, and motility difficult. Ejaculates vary in color from nearly clear to milky white, depending on the concentration of spermatozoa,19,20 and a comparatively high proportion of morphologic abnormalities (i.e., 40%) is common.13 Unlike the progressive motility of sperm seen in other domestic ruminants, only oscillatory movement is seen in the ejaculate of llamas and alpacas.12,21

The role of high viscosity of camelid semen is not known, but it may create a type of sperm reservoir22 or may be important for maintaining sperm viability within the uterus.23 To facilitate handling and processing semen, attempts have been made to liquefy the ejaculate. In a study designed to test the effectiveness of enzymes for liquefying semen (i.e., collagenase, fibrinolysin, hyaluronidase, or trypsin),24 collagenase was effective in eliminating semen viscosity within 5 minutes with little or no influence on sperm characteristics. A mechanical technique of liquefying the ejaculate25,26 involved alternately aspirating and expelling the ejaculate through a needle; the technique effectively liquefied the ejaculate and had little influence on other characteristics of semen.

Little information is available on the use of semen extenders. Motility of llama semen was conserved for 24 hours after collection when diluted with a solution of 30% BSA and 60% glucose and placed in a refrigerator.8 Dilution with a TRIS–glucose–egg yolk semen extender without elimination of viscosity resulted in poor motility (5%) after 3 hours,15 but recent results with prior mechanical liquefaction and preservation at 5°C improved motility. Pacheco27 reported the use of semen diluted with 10% egg yolk and 3% citrate and although no information was given about semen quality after dilution, a pregnancy rate of 60% after AI was reported. In another study,28 semen collected by AV and diluted with TRIS and EDTA extenders with or without surfactant (Equex STM) was prewarmed to 38° to 40° C and maintained at that temperature until insemination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree