Chapter 44 Scabies, Notoedric Mange, and Cheyletiellosis

Sarcoptic mange, notoedric mange, and cheyletiellosis are parasitic dermatoses caused by acarine mites living on or within the skin of the host animal. Exposure to these mites and the corresponding incidence of parasitic dermatoses are closely related to environmental factors, especially animal contact and living in endemic areas. Although these mites are not completely host specific, they exhibit host preference and have zoonotic potential for causing dermatoses in humans.

SCABIES

Etiology

• Scabies (sarcoptic mange) is a non-seasonal, intensely pruritic papulocrustous dermatosis of dogs caused by the epidermal mite Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis (Fig. 44-1). Although fairly host specific, the mite can affect cats, foxes, and humans. Sarcoptic acarosis is rare in the cat, and an underlying immunosuppressive disease (i.e., feline immunodeficiency virus infection) is likely to be concurrent and should be investigated.

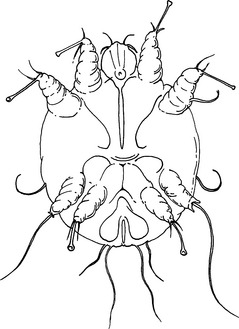

• The adult mite is microscopic (200–400 μm), roughly circular in shape. It is characterized by two pairs of short legs anteriorly that bear long, unjointed stalks with suckers and two pairs of rudimentary legs posteriorly that do not extend beyond the border of the body.

• The parasite completes its life cycle (egg–larva–nymph–adult) in 12 to 21 days in tunnels and molting pockets in the stratum corneum of the epidermis. Mites burrow into the lower stratum corneum but rarely penetrate further. The female may reach the stratum spinosum as she creates the tunnel and deposits eggs.

• Although scabies mites live in the superficial layers of the skin, the mite antigen can reach the lower epidermal and dermal skin and induce a humoral and cell-mediated immune response. Dogs may develop a protective immunity after successful treatment and cure of a scabies mite infestation. Thus, subsequent reinfestation may not result in clinical signs. The exact mechanism of protective immunity is not fully understood, and its elucidation is further complicated by crossreactivity and cross-sensitization to house dust mites.

• Although the parasite is susceptible to high temperature and drying, it can live in the environment for up to 21 days under ideal environmental conditions.

• Scabies is highly contagious and is primarily transmitted by direct contact with an infested animal. Fomite and fur transmission to humans or other animals can occur via contact with grooming equipment or at kennels.

• The incubation period is highly variable and is dependent on factors such as the number of mites present, the time required for the development of hypersensitivity, and the treatments prescribed. The use of systemic corticosteroids may allow the mite population to increase more rapidly.

• Observable dermatologic changes are often out of proportion with the number of mites present on the animal, suggesting that cutaneous hypersensitivity to mite antigen plays an important role in the course of disease.

Clinical Signs

• The body sites typically involved include the ear pinnae margins, elbows, hocks, and ventral chest. Lesions and pruritus can become widespread, but the dorsum is usually spared.

• Early lesions are characterized by erythematous papular eruptions that develop thick crusts that may be yellow in color. With time, self-excoriation results in patchy to widespread alopecia, and generalized papulocrustous dermatitis develops. Hyperpigmentation and lichenification are the most dominant lesions in chronic cases due to constant self trauma at affected body sites.

Diagnosis

• Major differential diagnoses include cutaneous adverse food reaction (CAFR) and flea bite hypersensitivity (FBH), as these diseases can also be intensely pruritic. The distribution patterns characteristic of CAFR, FBH, and scabies can mimic each other in chronic cases, especially if secondary infections are present.

• Additional differentials to consider include cheyletiellosis, Otodectes cyanotis dermatitis, dirofilariasis, Pelodora dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis.

• Malassezia dermatitis and superficial pyoderma are also important differentials, and these secondary infections should be considered at the initial presentation. These infections can be intensely pruritic in animals hypersensitive to the organisms. Dermatophytosis is not usually pruritic, but it should be pursued as a differential if therapy does not resolve the clinical signs.

History

• Rapid onset of intense pruritus and rapid progression of lesions with inconsistent response to corticosteroids.

• Likely source of infection. Inquire about visits to training or boarding facilities, dog shows, dog parks, grooming parlors, etc., approximately 1 month prior to the onset of the pruritus.

• Potential exposure of the affected animal to other species known to harbor the mite, especially fox.

Diagnostic Tests

• To make a definitive diagnosis, the clinician must demonstrate the presence of any life stage of the mite and/or eggs. Perform superficial skin scrapings and fecal flotation. Remember that the mite is often very difficult to find, even with multiple skin scrapings.

• To obtain superficial skin scrapings, identify non-excoriated and recently affected body sites where crusted papules are visible. Avoid lesions of chronic pruritus, such as severe lichenification. Usually the ear pinnae, elbows, hocks, and ventral thorax are best. Apply a liberal amount of mineral oil to the skin surface and scrape a wide anatomic area with a #10 scalpel blade. Transfer the collected material to a glass slide and examine under 10-power magnification and reduced light. Carefully evaluate all microscope fields for any life stage of the mite. Even finding an egg or brown, oval fecal pellets in the material is diagnostic.

• Of dogs with scabies and ear pinna lesions, 75% to 90% have a positive pinnal-pedal reflex. In one study, this test had a sensitivity of 81.8% and a specificity of 93.8%.

• To perform this test, maneuver the tip of an affected ear pinna and rub it vigorously against the base of the ear for at least 5 seconds. At the same time, observe the ipsilateral hind limb. If the dog moves the limb in an attempt to scratch, the test is positive.

• Most dogs develop a humoral antibody response between 2 and 5 weeks after infection with scabies. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) used to detect serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to Sarcoptes mite antigen is available (Imovet Sarcoptic). The test has a reported diagnostic sensitivity of 83% to 92% and a specificity of 89.5% to 96%. It may be helpful in the diagnosis of canine scabies when the disease is suspected, but mites cannot be identified.

• Submission forms may be downloaded from the Athens Diagnostic Laboratory website at http://hospital.vet.uga.edu/dlab/athens/access.pdf.

• House dust mite, a common allergen in dogs with atopic dermatitis, shares some antigens with S. scabiei. Patients with scabies may have positive intradermal and serum allergy test results to house dust mite allergens. Thus, rule out scabies definitively prior to making a diagnosis of atopic dermatitis and performing allergy testing.

Treatment

• Emergence of resistant strains of the Sarcoptes organism and an array of available commercial products make selection of parasiticides difficult. Products highly efficacious in one geographic location may be ineffective in another.

• A number of acaricidal products have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of sarcoptic mange. Many of these products have real potential for toxicity and adverse reactions in certain breeds or species. Idiosyncratic reactions have also been reported in certain breeds at therapeutic doses.

• Initially, use a product approved and licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the target animal species and disease being treated. Any other application is extra-label usage of that drug. The FDA recognizes the need for extra-label usage in veterinary medicine, but you should obtain informed consent from the owner. If the FDA product cannot be used in a particular animal, attempt to use a drug that is approved for the species you are treating but for another disease.

• Evaluate heartworm status in all dogs prior to treatment. Some topical treatments are systemically absorbed.

• Systemic therapies are emerging and proving to be efficacious in the treatment of scabies in dogs. The macrocyclic lactones ivermectin (Ivomec, Merial Animal Health), milbemycin oxime (Interceptor, Novartis Animal Health), moxidectin (Cydectin, Fort Dodge Animal Health), and selamectin (Revolution, Pfizer Animal Health) are effective.

Selamectin

• Selamectin is a novel semisynthetic avermectin produced by Streptomyces avermitilis. In the United States, it is approved for the prevention of canine heartworm, flea control, deworming, and the treatment of sarcoptic mange and Otodectes cyanotis in dogs. It is also licensed for the control of Dermacentor variabilis infestations. For cats, it is labeled in the United States for the prevention of dirofilaria, fleas, and Otodectes cyanotis. It is also used for gastrointestinal nematodes in cats. In cats and dogs, selamectin may be given at 6 weeks of age at the label dosage of 6 to 12 mg/kg applied to the skin.

• Two treatments with selamectin 30 days apart at a dose of 6 to 12 mg/kg applied to the skin on the dorsal neck is reported by the manufacturer to be 100% efficacious for the treatment of scabies by day 60. Field and laboratory trials were comparable to a reference positive-control product. We frequently use selamectin every 14 days for two to three treatments for the treatment of confirmed or suspected scabies acarosis. This regimen would be extra-label usage. Environmental treatment may not be necessary.

Milbemycin Oxime

• Milbemycin oxime (Interceptor, Novartis Animal Health) is a macrolide antibiotic made from the fermentation of Streptomyces hygroscopicus and is approved for monthly heartworm prophylaxis. It is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of scabies, but it may be an alternative treatment, especially in breeds of dogs in which ivermectin is contraindicated and the FDA-approved product cannot be used.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree