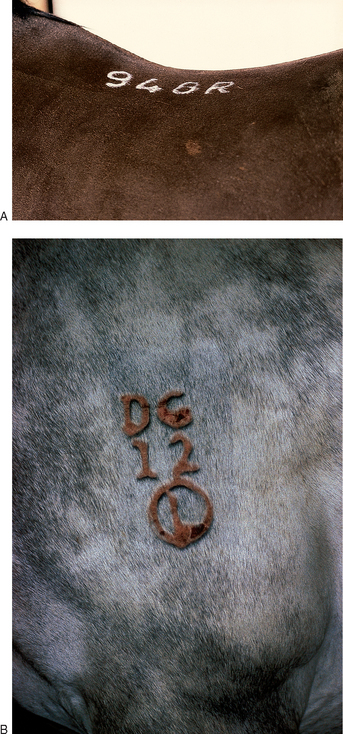

Chapter 3 The body score system can be used in addition to the weight; the ideal adult body condition score should remain between 4 and 6 (on a scale of 10).1 The methods available for identification of the animals include several visible means, some hidden means and some that rely on documentation. Most of the effective methods are permanent, but temporary identification can be useful under some conditions (e.g. short-term movement to a stud farm). Hoof branding (Fig. 3.1) is a semi-permanent method of identification, but of course the marks are lost as the hoof grows out. Also, it is possible to tamper with the marks by altering the figures to some extent. Nevertheless, it is a reasonably effective way that is painless (hopefully) and will certainly be identifiable for some 4–6 months. It can be repeated as many times as necessary. Usually a postcode/zipcode or telephone number is used, which can be spread over all four hooves. Freeze marking (Fig. 3.2) has been used for many years as a means of identification. It relies upon the change in color of the hair from body color to white when the skin is subjected to a defined cycle of freezing. The freezing is not enough, however, to cause serious freezing leading to ulceration of the skin. In gray horses the method requires a harder freeze because the intention is to create a hairless mark rather than just a change in the color of the hair coat. A white mark on a white-haired horse would probably not be obvious! In many cases the freeze mark is not very obvious until the area is clipped, but most freeze marks are obvious from a distance. Fig. 3.2 (A) A freeze brand. (B) A freeze brand can suggest both identity and a possible insurance history. Hot branding (Fig. 3.3) commonly takes two forms. The first is a standard identification mark that is used for specific breeds of horse. The second is some form of specific identification; historically, this was used to identify the owner of the horse or its origin, but it could equally be used to add numbers and letters in combination so that the animal can be identified permanently. The brand is usually applied at an early age (when restraint is more practicable). The effect is obtained by creating an obvious, defined shaped scar. No hair grows on the scar and it is therefore visible from a distance and regardless of the hair coat status (winter/summer). • A very time-consuming, and therefore expensive, procedure if performed properly by a veterinary surgeon. Most breed societies will only accept certificates of identification if they are signed by a veterinary surgeon. • The passport or ID form is required for comparison. • Open to abuse if blank forms fall into the wrong hands. Forged signatures and false sketches and narratives are easy to prepare. • Some difficulties with colors, especially in bay/chestnut foals that subsequently turn gray. • Lack of credibility with respect to the individual horse unless accompanied by a certificate of authenticity signed by a veterinary surgeon. • Some breeds such as the Fell pony have few if any identification marks apart from whorls and these may be difficult/impossible to see on a photograph. • Will depend heavily on photographic quality. In many cases it is impossible to see whorls or small marks/scars clearly. • New scars or skin damage from injury, etc. may change the appearance significantly from that in the photograph. Foals are usually considered to be effectively covered for up to 6–8 weeks of age through colostral transfer of antibody (see p. 374) provided that the mare received a booster vaccination in the last trimester of pregnancy. If a mare has not been vaccinated for between 1 and 2 years before foaling the duration of transferred immunity is probably inadequate. If there is any doubt about either the effectiveness of the vaccination of the mare or the efficiency of colostral (passive) transfer of immunity (see p. 377) it is common practice to administer a single or repeated doses of between 1500 and 6000 IU of tetanus antiserum. This will usually confer effective protection for up to 12 weeks of age.3 The administration of a tetanus toxoid at, or shortly after, birth is controversial, but in theory at least there should be no particular problem with vaccination at 2–4 weeks of age.4 However, most authorities do not recommend vaccination at birth of a foal that has effective passive transfer on the basis that passive antibodies will interfere with active immunity for a primary vaccination. Repeated vaccination during this time may indeed result in poor long-term immunologic response to the vaccine, and in some cases there may be no effective response. However, some authorities consider that active vaccination in the face of passive maternal immunity is effective.5 The vaccines do not appear to prevent the development of the neurological form of the disease. There are three types of vaccine available: • A killed oil-based vaccine that has been used for many years to prevent abortion. The vaccine is administered to pregnant mares at 3, 5 and 7 months of gestation. Stallions are vaccinated as for nonpregnant mares (i.e. by annual booster). • Modified live virus vaccine. Although this vaccine does confer good immunity against both virus strains, it should not be used in pregnant mares. • Killed bivalent vaccine with immune stimulating complex. These vaccines are widely available and are effective in controlling abortion as well as respiratory disease. This disease causes abortion, infertility, upper respiratory tract disease and arteritis (see p. 259). It has a worldwide distribution, but some areas are free of the disease. Vaccines are effective in preventing the disease but do not result in the cure of an infected carrier stallion (see p. 259). An annual booster dose is given to all breeding stock at least 3 weeks before breeding. Vaccination is usually by an inactivated bivalent or trivalent vaccine and the conferred immunity from a primary course is probably less than 6–9 months.5 The first dose of vaccine for foals is usually administered at 4–6 months of age. The primary vaccination course is two doses given 3–4 weeks apart; seroconversion is then measured and vaccination repeated until a protective level is achieved. Annual or bi-annual boosters are usually given. Passive immunity is probably conferred for 12 weeks but little is known about this.

ROUTINE STUD MANAGEMENT PROCEDURES

GENERAL PROCEDURES

Weight and condition

Identification procedures

Hoof branding

Tattoo (lip/gum or ear)

Freeze marking

Hot branding

Identification by natural markings/scars (permanent alterations)

Disadvantages

Photographic identification

Disadvantages

Vaccination

Tetanus

Equine herpesvirus 1 and 4 (rhinopneumonitis)

Equine viral arteritis

Equine viral encephalitis

Rabies