Chapter 10

Routine Neutering of Companion Animals

- 10.1 Introduction

- 10.2 Chemical Sterilisation

- 10.3 Surgical Neutering and Its Impacts on Animal Welfare

- 10.3.1 The question of whether to neuter in light of potential effects on health-related welfare

- 10.3.2 The question of when to neuter

- 10.3.3 Conclusions (based on medical evidence)

- 10.3.1 The question of whether to neuter in light of potential effects on health-related welfare

- 10.4 Neutering and Positive Welfare

- 10.5 Neutering and Ethical Theories

10.1 Introduction

The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), among others, strongly encourages owners of dogs and cats to have their companion neutered.

By having your dog or cat sterilized, you will do your part to prevent the birth of unwanted puppies and kittens. Spaying and neutering prevent unwanted litters and may reduce many of the behavioral problems associated with the mating instinct…Early spaying of female dogs and cats can help protect them from some serious health problems later in life such as uterine infections and breast cancer. Neutering your male pet can also lessen its risk of developing benign prostatic hyperplasia (enlarged prostate gland) and testicular cancer…Most pets tend to be better behaved following surgical removal of their ovaries or testes, making them more desirable companions.

(AVMA, n.d.)

However, not all vets take this view. Across continental Europe, vets have traditionally been more reluctant to neuter companion animals, especially dogs. (We will use ‘neuter’ to refer to sterilisation of both sexes.) In Sweden, for example, it was illegal to castrate a male dog until 1988, unless there was a specific medical reason for doing so. The official view of Swedish vets is still much more restrictive than that of the AMVA. The section of the Swedish Veterinary Association dealing with companion animals issued a statement (SVS, 2011) in which routine surgical neutering of dogs is rejected as sound policy. However, the idea of routine neutering of companion animals seems to be spreading. (By routine neutering, we mean neutering of healthy animals becoming the norm or ‘default setting’.)

Neutering may be of ethical significance in several ways. It plays an important role in discussions about unwanted and unowned cat and dog populations, which raises ethical issues; we will explore these issues about populations in Chapter 13, and put them on one side here. In this chapter, we are interested in a narrower set of concerns: the routine neutering of companion animals kept indoors and not permitted to roam, or always kept under restraint when outdoors – that is, animals living in situations where it is impossible, or extremely unlikely, that mating will occur. This applies to cats kept wholly indoors, and to many dogs living in urban or suburban environments in Western industrialised countries.

Neutering is not the only form of reproductive control in companion animals, although it is by far the most popular. So we will begin this chapter with a brief discussion of other forms of reproductive control, and why they are not widely used. Then we will move on to the substance of the chapter: surgical neutering. We will consider the short- and long-term impacts of neutering in terms of animals’ welfare, and the relations between humans and their animal companions. Then we will explore broader ethical issues that neutering may raise from different ethical perspectives, including the ideas that neutering may deprive animals of certain aspects of positive welfare, that it may infringe on their rights, and that it might be either an expression of care, or alternatively of domination, within a human–animal relationship.

10.2 Chemical Sterilisation

While surgical neutering is by far the most popular form of reproductive control in companion animals, temporary/reversible control of reproduction and behaviours related to reproduction (‘chemical sterilisation’) is also possible for cats and dogs of both sexes, and can be achieved pharmacologically, using hormonal products. Many hormonal products cause similar side effects to those seen following neutering, for example, increased body weight, hair coat changes, or predisposition to diabetes mellitus (see below); but most side effects resolve when the treatment is stopped. Some hormonal products have additional side effects, for example, progestogens may predispose bitches to pyometra (a uterine infection) and oestrogens may cause dose-related bone marrow suppression, which can result in a severe and possibly fatal blood disorders, although side effects are less common with more modern preparations (Romagnoli & Sontas, 2010).

Although chemical sterilisation is sometimes used as a temporary measure in breeding animals, or to test whether loss of hormones would alter unwanted behaviour (particularly in male dogs) prior to surgical neutering, it is not routinely used for long-term reproductive control of companion animals. This may be due to concerns about potential adverse effects with prolonged or repeated use of hormonal products, but equally, there are concerns about convenience and confidence. Neutering is a one-off procedure guaranteed to permanently prevent reproduction and associated behaviours. Chemical sterilisation is temporary, and to remain effective, may require daily administration of oral tablets, or repeated injections (although implants lasting 6–12 months are available, and vaccines are being developed). Chemical sterilisation, as a means of reproductive control, therefore involves some inconvenience to the owner, and in some cases stress to the animal of repeated visits to the vet, and these ‘costs’ – as well as economic ones – over the lifetime of the animal may therefore compare unfavourably with neutering. Since neutering is far more common than chemical sterilisation, we will, in the rest of this chapter, focus on neutering as the principal means of controlling reproduction in companion animals.

10.3 Surgical Neutering and Its Impacts on Animal Welfare

Neutering involves removal of the animal’s reproductive organs, and is, therefore, permanent. Cats can become pregnant from 4 months onwards, although most reach puberty between 8 and 10 months (Joyce & Yates, 2011). Puberty in dogs is more variable, from 6 months onwards in smaller breeds, but often much later in large breeds. Routine neutering has traditionally been performed at around 6 months in cats and bitches, with male dogs castrated a few months later. However in some parts of the world, notably the United States, it has recently become common to neuter much earlier (6–16 weeks); we consider special questions raised by early neutering in Section 10.3.2.

Welfare impacts of neutering include the direct effects of the surgery itself, which involves an animal being left in unfamiliar surroundings with strangers, undergoing general anaesthesia and surgical trauma, and enduring some degree of pain; the risk of negative short-term side effects (e.g. inflammation at the site of the incision), and longer term costs and benefits, relating to incidence of disease, suffering, and length of life. However, research suggests that these impacts vary depending on the sex and species of the neutered animal. So, we will consider welfare within four categories here: female dogs (bitches), male dogs, female cats (queens) and male cats (toms).

10.3.1 The question of whether to neuter in light of potential effects on health-related welfare

10.3.1.1 Female dogs

Neutering female animals involves removal of the ovaries; in bitches, it is normal also to remove the uterus. Studies have shown, however, that there are no clear advantages from removing the uterus too; and just removing the ovaries is a more straightforward and less invasive surgery (Van Goethem et al., 2006). So, there seems in most cases to be a welfare justification here for changing the normal method of neutering bitches (in addition, laparoscopic – or ‘keyhole’ – procedures are becoming increasingly available). But what about the health and welfare issues raised by neutering itself, independent of the method?

Neutering bitches prevents complications from pregnancy and potential diseases in the ovaries and uterus, such as developing the uterine infection, pyometra, which occurs in 15.2% of entire bitches by 4 years of age (Fukuda, 2001), and thereafter becomes increasingly common. It also significantly reduces the risk of mammary tumours, the most common tumour of female dogs, of which 50% are malignant (Robbins, 2003). Reducing the risk of mammary tumours is frequently quoted as a major reason for early neutering; neutering before the first season reportedly reduces the risk of developing mammary tumours to less than 0.5% (Schneider, Dorn & Taylor, 1969). However, a recent systematic review of the evidence by Beauvais, Cardwell & Brodbelt (2013) concluded that due to limited evidence and potential bias in studies, the evidence that neutering reduces the risk of mammary tumours is weak and not a sound basis for firm recommendations. Nonetheless, it is widely accepted that neutered bitches on average live longer than intact ones, perhaps because of the decreased incidence of reproductive disease.

There are, though, also negative impacts of neutering: complication rates of up to 20.6% have been reported (Burrow, Batchelor & Cripps, 2005), and occasionally, bitches die from peri-operative bleeding. One of the main complications is the development of urinary incontinence, particularly in large breeds: neutering increases the risk 7.8-fold (Thrusfield, Holt & Muirhead, 1998). In most cases, the incontinence is treatable, although half of the bitches may require surgery. Furthermore, as we saw in Chapter 8, neutering increases the risk of obesity. There are also impacts that may make neutered bitches more difficult to live with: some studies suggest that neutered bitches are more aggressive than entire bitches, though the reasons for this are unclear.

Two recent studies, concerning both male and female dogs, investigated the risk of neutered dogs of specific breeds developing hip dysplasia (HD) or cranial cruciate ligament disease (CCL), or three kinds of cancer – lymphosarcoma (LSA), hemangiosarcoma (HSA), and mast cell tumour (MCT) – compared to entire animals. In the first, Torres de la Riva et al. (2013) found that the incidence of all five diseases increased in Golden Retrievers of both sexes – to some extent depending on whether neutering was performed ‘early’ (before 1 year of age) or ‘late’ (after 1 year of age). Late neutered bitches had four times the incidence of HSA (8%) of intact and early neutered females, and 6% had MCT, compared to none in intact females.

In a follow-up paper, Hart et al. (2014) compared the effects of neutering Golden Retrievers and Labrador Retrievers on the occurrence of three joint disorders (HD, CCL and elbow dysplasia) and four types of cancers (LSA, HSA, MCT and mammary cancer). The study found that breeds respond very differently to the effects of neutering. The incidence of joint disease in intact males and females of both breeds is around 5%, but this was nearly doubled in Labrador Retrievers, and increased four- to fivefold in Golden Retrievers, neutered before 6 months of age. The occurrence of one or more cancers in intact dogs ranged from 3% to 5%, except in Golden Retriever males where incidence was 11%. While neutering Labrador Retrievers of either sex at any stage had little effect on increasing cancers, and the same was found for male Golden Retrievers (except for LSA which increased significantly if they were neutered before 6 months old), neutering a female Golden Retriever at any period beyond 6 months increased the risk of one or more cancers to three to four times that of intact females.

Despite these findings, on balance, in welfare terms, it appears that the long-term health related welfare of bitches – that is, with respect to longevity and risk of suffering from disease in later life – is likely to be improved, or at least not reduced, by neutering.

10.3.1.2 Male dogs

Male dogs are typically castrated by surgical removal of the testicles. This surgery itself rarely causes immediate complications. However, unlike the case of female dogs, overall there are probably increased risks of significant negative long-term consequences for health-related welfare. Castration of male dogs removes the risk of testicular disease (e.g. testicular cancer), and reduces the risk of androgen-dependent diseases such as perineal hernias. However, as well as increasing the risk of obesity, neutering also significantly increases the risk of prostate and bladder cancer: although prostate cancer is rare in male dogs (0.2–0.6% incidence), it is almost always malignant (Bryan et al., 2007). Castration also slightly increases the risk of other cancers such as bone and cardiac cancer; for example, osteosarcoma (OSA), a highly aggressive bone tumour, occurs twice as frequently in neutered dogs compared to intact dogs (Ru, Terracini & Glickman, 1998). Breed also appears to be significant: Rottweilers neutered before 1 year of age have a 1 in 4 lifetime risk of developing OSA, which is significantly higher than entire dogs (Cooley et al., 2002). A similar increase in certain serious diseases in neutered males of specific breeds was found by Torres de la Riva et al. (2013) and Hart et al. (2014) (see previous section). Torres de la Riva et al. (2013) also found that ‘early’ neutered male Golden Retrievers had double (10%) the incidence of HSA of intact males, and 10% had LSA (three times the number seen in intact males).

Sometimes, male dogs are castrated to limit aggression and other behavioural problems (which can cause injury to the dogs themselves, as well as being problematic for their owners; see Chapter 9). However, the effect of neutering on male dog behaviour seems to be variable. One study suggests that neutered male dogs over 1 year old were most likely to have bitten someone (Guy et al., 2001) – though the biting behaviour may have been the reason these dogs were neutered, and not all studies support this finding. Neutering does seem to reduce roaming and urine marking in male dogs, and there is some evidence that neutering males of certain breeds makes them more trainable (e.g. Rottweilers and Shetland Sheepdogs) (Serpell & Hsu, 2005).

Bringing all these findings together, with respect to the animals’ own welfare, the costs of routinely neutering male dogs, in terms of the increased risk of very serious diseases, probably outweigh the benefits. So, justification for routine neutering of confined male dogs, then, does not seem to follow from claims about the dogs’ own welfare.

10.3.1.3 Female cats

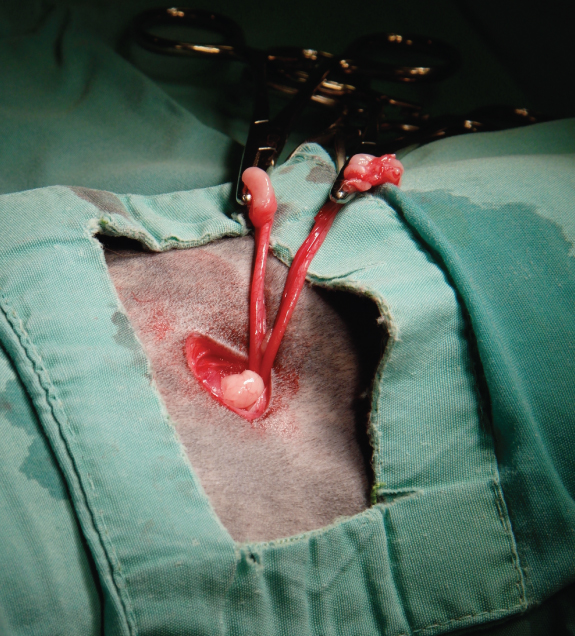

Female cats, like female dogs, are usually neutered by removing the uterus and the ovaries, and the surgery itself can cause complications (Figure 10.1). However, there are longer-term benefits to the surgery. Health risks from pregnancy are avoided (and since confined cats may escape, this is a more significant possibility than with bitches).

Figure 10.1 Cat spay. The procedure is often performed through a small flank incision, and both the ovaries and uterine horns are exteriorised and removed.

(Image used courtesy of Sandra Corr.)

Neutering female cats significantly reduces the risk of mammary tumours, which in cats have an 80–90% chance of being malignant, although they occur at a much lower frequency than in bitches. Neutering before 6 months results in a 91% reduction in the risk of developing mammary carcinomas (Overley et al., 2005), and prevents other mammary diseases. Neutered female cats do not have more urinary tract problems, and appear to show less aggression than intact female cats (Finkler & Terkel, 2010). The main health-related welfare problem for neutered cats (of both sexes) is a substantially increased risk of obesity, which can lead to diabetes and other problems (see more about this in Chapter 8). Neutered cats of both sexes are significantly more likely to become obese than entire cats (Nguyen et al., 2004) and are at significantly greater risk of becoming diabetic (Panciera et al., 1990).

On balance, then, there are some welfare benefits to female cats from being neutered, although in terms of avoiding serious disease, these seem weaker than the welfare reasons to neuter bitches. The welfare costs, at least in terms of obesity, are to some degree avoidable. So, on this basis at least, neutering looks as though it will improve, or at least not reduce, welfare.

10.3.1.4 Male cats

In male cats (toms), as in male dogs, castration is the only practiced form of surgical neutering. Unlike in dogs, both testicular and prostate disease are very rare in toms (Reichler, 2009), so neutering has little positive or negative direct impact on these aspects of welfare. The main welfare issue for the tomcat itself is, as with female cats, a significantly increased risk of obesity and of diseases that follow obesity, such as diabetes.

Tomcats are frequently neutered, however, to make them easier to live with – in particular to reduce urine spraying, aggression and roaming. Castration does seem effective in eliminating or significantly reducing urine spraying, and somewhat effective in reducing aggression and risky behaviour. So, neutering may reduce the likelihood of tomcats experiencing negative welfare impacts (by reducing risks from fighting and roaming), and it could indirectly benefit welfare, through creating better relations with owners than entire male cats could have; we will consider this further below.

10.3.2 The question of when to neuter

Many associations, such as the AVMA and Association of Shelter Veterinarians, are increasingly recommending early neutering (pre-pubertal gonadectomy) primarily to reduce the unwanted pet population. In this context, ‘early’ typically means between 6 and 16 weeks of age (Kustritz, 2002; Looney et al., 2008) not just under 1 year, as in the studies reported in the previous section. Early neutering has been slow to gain widespread acceptance amongst European vets however, due to concerns over the safety of general anaesthesia and surgery in young animals, and the effects of removing reproductive hormones before sexual maturity. But what does the evidence show?

10.3.2.1 Peri-operative concerns

No increased anaesthetic risks have been associated with early neutering, (Brodbelt et al., 2008), and the surgery is quicker to perform, with minimal bleeding (Howe, 1997; Kustritz, 2002) and fewer post-operative complications (Aronsohn & Faggella, 1993; Howe, 1997).

10.3.2.2 Long-term effects

Studies comparing early neutering to traditional neutering have produced conflicting results. Some studies have failed to identify differences in potential long-term effects, either generally (Kustritz, 2002), associated with the occurrence of hip dysplasia, urinary incontinence or vaginitis in puppies (Howe et al., 2001), obstructive urinary tract disease (Howe et al., 2000), or urethral diameter (Root et al., 1996; Stubbs et al., 1996) in male cats, or obesity levels (Howe et al., 2000; Root, 1995; Stubbs et al

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree