Chapter 3 Reptiles

Case 3.1

Physical examination

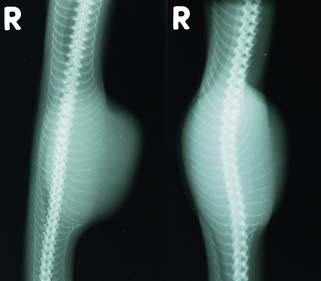

The snake was presented with a good body condition and an unimpaired general health. The mucous membranes of the oral cavity and pharynx appeared unsuspicious and pink coloured. In the cranial third of the body, approximately. 8 cm caudal to the occiput, an 8 cm long and 3 cm wide, tough-elastic, non-moveable swelling was present (Fig. 3.1). Nothing abnormal was detectable on the rest of the snake’s body by adspection and palpation. The righting reflex and the cloacal tone were normal. Survey radiographs were taken (Fig. 3.2) and ultrasonographic examination of the neck region was performed. In addition, a sonographically-controlled fine needle biopsy of the mass was taken.

Results

On radiographs, the distension appeared homogeneous, radiopaque, similar to soft tissues. Other organs, as assessable, appeared normal

On radiographs, the distension appeared homogeneous, radiopaque, similar to soft tissues. Other organs, as assessable, appeared normal

Ultrasonographic examination and colour Doppler sonography revealed the swelling as a homogeneous, strongly vascularized, 8 cm long and 3 cm wide mass. There were no clear borders to other surrounding tissue layers visible

Ultrasonographic examination and colour Doppler sonography revealed the swelling as a homogeneous, strongly vascularized, 8 cm long and 3 cm wide mass. There were no clear borders to other surrounding tissue layers visible

Please evaluate the clinical history, Figs 3.1 and 3.2, the results of the physical examination and clinical diagnosis laboratory tests.

![]() 2. List your differential diagnoses.

2. List your differential diagnoses.

Differential diagnoses for swellings/distensions in snakes

Abscess following bacterial or mycotic infection, mechanical trauma, injuries caused by companions or food animals

Abscess following bacterial or mycotic infection, mechanical trauma, injuries caused by companions or food animals

Granuloma (e.g. fungal, Mycobacteria spp.)

Granuloma (e.g. fungal, Mycobacteria spp.)

Obstipation, coprostasis, caused by mismanagement or parasitic infection (e.g. Cryptosporidia spp.)

Obstipation, coprostasis, caused by mismanagement or parasitic infection (e.g. Cryptosporidia spp.)

Neoplasia, spontaneous or caused by viral agents (e.g. retrovirus, C-type oncornavirus)

Neoplasia, spontaneous or caused by viral agents (e.g. retrovirus, C-type oncornavirus)

Bone deformations following bacterial infections (e.g. Salmonella spp.) or caused by metabolic disorders

Bone deformations following bacterial infections (e.g. Salmonella spp.) or caused by metabolic disorders

Recent food uptake, especially in an environment too cold for the animal

Recent food uptake, especially in an environment too cold for the animal

Therapy

The snake was hospitalized to perform surgical removal of the mass. Previous to surgery the snake received premedication (Table 3.1).

| Tiletamin/zolazepam | 5 mg/kg IM |

| Isoflurane | 3% inhalant mix with oxygen to maintain inhalation anaesthesia |

| Carprofen | 4 mg/kg IM |

| Fluids | Ringer’s lactate 20 ml/kg SC BID |

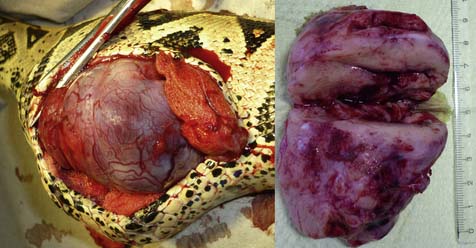

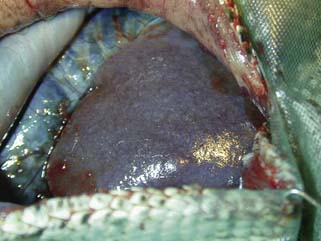

After anaesthesia and analgesia, the skin around the swelling was disinfected with an alcoholic antiseptic. Incision of the skin was made between the second and third row of lateral scales and underlying muscle layers separated by blunt dissection. The mass (Fig. 3.3) was localized inside the oesophagus, which was incised to a length of 10 cm. The mucous membranes of the oesophagus were extensively infiltrated by the growth, so that a complete removal would have been impossible. As an extirpation was assumed to be connected with huge bleeding and tissue damage the animal was euthanized during surgery. Afterwards the greasy-mushy, strongly vascularized mass (Fig. 3.3) was removed and sent for histopathological examination.

Catao-Dias J.L., Nichols D.K. Neoplasia in snakes at the National Zoological Park, Washington, DC (1978–1997). J. Comp. Pathol.. 1999;120:89–95.

Fry F.L. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of reptilian neoplasms with a compilation of cases 1966–1993. In Vivo. 1994;8:885–892.

Maulden G.N., Done L.B. Oncology. In: Mader D.R., ed. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. second ed. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:299–322.

Ramsay E.C., Munson L., Lowenstin L. A retrospective study of neoplasia in a collection of captive snakes. J. Zoo Wildl. Med.. 1996;27:28–34.

Sykes J.M., Trupkievicz J.G. Reptile neoplasia at the Philadelphia Zoological Garden 1990–2002. J. Zoo Wildl. Med.. 2006;37(1):11–19.

Case 3.2

Clinical diagnosis laboratory

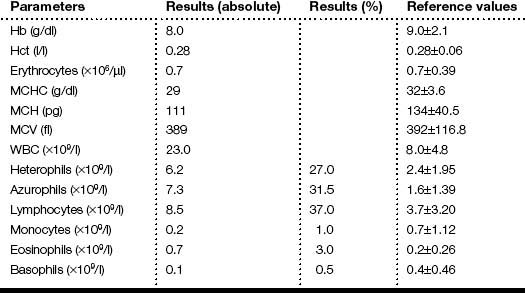

The results of the clinical diagnosis laboratory assays are shown in Tables 3.2 and 3.3.

Table 3.3 Blood chemistry values of the boa constrictor

| Analysis | Results | Reference values |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium (mmol/l) | 3.8 | 4.0±0.90 |

| GOT (U/l) | 3 | 32±45 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/l) | 0.82 | 1.5±0.65 |

| Total protein (g/l) | 84 | 70±13 |

| Uric acid (μmol/l) | 275 | 292±220 |

Reference values: ISIS Physiological Reference Values, 2002.

Results

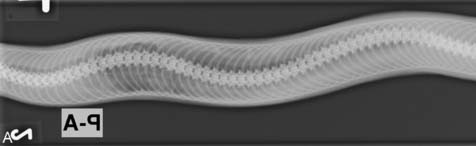

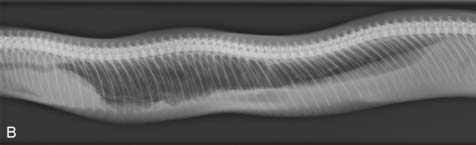

Radiography revealed a worm-like structure in the lung, lung consistency was increased and the margins were not clearly defined. The intrapulmonary bronchus was visible

Radiography revealed a worm-like structure in the lung, lung consistency was increased and the margins were not clearly defined. The intrapulmonary bronchus was visible

Haematology revealed a moderate leucocytosis, with azurophilia and heterophilia

Haematology revealed a moderate leucocytosis, with azurophilia and heterophilia

Please evaluate the clinical history, Fig. 3.4a, b and the results of the physical examination and clinical laboratory diagnostic tests.

Differential diagnoses

Endoparasitosis larva migrans of Strongyloides spp. or Rhabdias spp. in the lung

Endoparasitosis larva migrans of Strongyloides spp. or Rhabdias spp. in the lung

Pneumonia of bacterial or viral origin

Pneumonia of bacterial or viral origin

![]() 4. What would be your next diagnostic steps to ascertain the diagnosis?

4. What would be your next diagnostic steps to ascertain the diagnosis?

Further diagnostic steps

The images obtained are shown in Figs 3.5 and 3.6.

Therapy (Table 3.4)

| Fenbendazole | 50 mg/kg PO SID × 5 days |

| Removal of pentastomidae | Minimally invasive by endoscopy, removal of 4 pentastomids |

| Fluids | Lactated Ringer’s solution 20 ml/kg SC |

| Enrofloxacin | 10 mg/kg IM SID × 5 days post-surgery |

Chinnadurai S., DeVoe R. Selected infectious diseases of reptiles. Vet. Clin. North Am. Exot. Anim. Pract.. 2009;12:583–596.

Foldenauer U., Pantchev N., Simova-Curd S. Pentastomidenbefall bei Abgottschlangen (Boa constrictor). Diagnostik und endoskopische Parasitenentfernung. Tierärztliche Praxis. 2008;36:443–449.

Greiner E., Mader D.R. Parasitology. In: Mader D.R., ed. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:360–364.

Jacobsen E. Parasites and parasitic diseases of reptiles. In: Jacobsen E., ed. Infectious Diseases and Pathology of Reptiles. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2007:590–593.

Schumacher J. Reptile respiratory medicine. Vet. Clin. North Am. Exot. Anim. Pract.. 2003;6:213–231.

Case 3.3

Clinical examination

On presentation, the snake was in bad general condition (Figs 3.7 and 3.8). A moveable bulge cranial to the cloaca was palpable. A bluish tissue with a central lumen and a peripheral blind sac was detected by using a probe.

![]() 1. What is your interpretation of the clinical examination and Figs 3.7 and 3.8?

1. What is your interpretation of the clinical examination and Figs 3.7 and 3.8?

![]() 2. What are your differential diagnoses? List your diagnostic plan.

2. What are your differential diagnoses? List your diagnostic plan.

Therapy

It was decided to lavage the cloaca and the colon through the rectum with lubricant solution and massage the bulge caudally. A large amount of kidney beans were passed out (Fig. 3.9) but the massage induced intestinal prolapse (Fig. 3.10). This was corrected by placing transverse cloacal sutures (Fig. 3.11, Table. 3.5).

| Enrofloxacin 2.5% | 5–10 mg/kg IM SID for 10 days |

| Meloxicam | 0.1–0.2 mg/kg SID SC |

Gabrisch K., Zwart P., Schlangen P. Zwart P., Sassenburg L. Krankheiten der Heimtiere. seventh ed. Hannover: Schlütersche Verlagsgesellschaft GmbH & Co; 2008:739–794.

Girling S.J., Raiti P. BSAVA Manual of Reptiles. second ed. Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association; 2004:210–229.

Mader D.R. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. second ed. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:675–682. 751–755

Case 3.4

Clinical examination

On presentation, the snake had a good body condition. It behaved motionless even when stimulated to move. The righting reflex was absent (Fig. 3.12). The palpation of the body was normal.

![]() 1. What are your differential diagnoses? List your diagnostic plan.

1. What are your differential diagnoses? List your diagnostic plan.

Clinical diagnosis laboratory

The results of the clinical diagnosis laboratory assays were as follows:

• Paramyxovirus-antibody titre was negative

• In blood smears no intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies were found, which cannot exclude IBD (retrovirus).

Therapy (Table 3.6)

| Enrofloxacin 2.5% | 5–10 mg/kg IM SID for 10 days |

| Serumproteins | Bioserin® (Paraimmunityinducer) 1 ml/kg TID PO for 7 days |

| Vitamin B-complex | Thiamine 30 mg/kg IM once |

| Fluids | 10–25 ml/kg; 1/3 Ringer’s lactate + 1/3 0.9% NaCl solution + 1/3 Glc 5% |

Post-mortem findings

Histology

Liver: a single histiocytic granuloma. There was a mild diffuse congestion. An infiltration of heterophil granulocytes in the sinusoids was found. Ziehl-Neelsen staining showed acid-fast organisms in the middle of the granuloma

Liver: a single histiocytic granuloma. There was a mild diffuse congestion. An infiltration of heterophil granulocytes in the sinusoids was found. Ziehl-Neelsen staining showed acid-fast organisms in the middle of the granuloma

Heart: mild degeneration of the myocytes

Heart: mild degeneration of the myocytes

Brain: mild gliosis and vacuolization of the white and grey brain substance (demyelination)

Brain: mild gliosis and vacuolization of the white and grey brain substance (demyelination)

Mader D.R. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. second ed. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:239–250. 675–682, 852–887

Gabrisch K., Zwart P., Schlangen P. Zwart P., Sassenburg L. Krankheiten der Heimtiere. seventh ed. Hannover: Schlütersche Verlagsgesellschaft GmbH & Co; 2008:739–794.

Girling S.J., Raiti P. BSAVA Manual of Reptiles. second ed. Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association; 2004:273–288.

Case 3.5

Clinical diagnosis laboratory examination

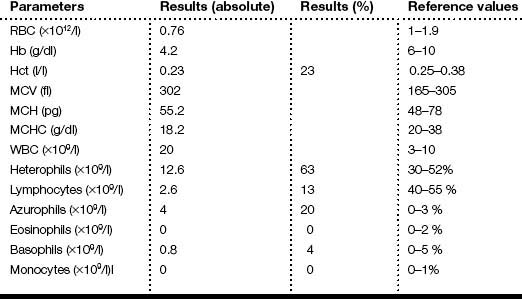

The results of the clinical diagnosis laboratory assays are shown in Tables 3.7–3.9.

Table 3.8 Blood chemistry values of the green iguana

| Analysis | Results | Reference values |

|---|---|---|

| Albumin (g/l) | 20 | 21–28 |

| ALKP (U/l) | 192.8 | 50–290 |

| Bile acids (μmol/l) | 43.1 | 2–17 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 11.4 | 8.8–14 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 99 | 104–333 |

| CK (U/l) | 399 | 200–700 |

| GGT (U/l) | 7 | < 0.1 |

| GOT (U/l) | 65 | 5–52 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 189 | 169–288 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 2.3 | 3–5 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 2.7 | 2–5 |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 142 | 158–183 |

| Total protein (g/l) | 74 | 50–78 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 47 | 53–691 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 0.8 | 2–10 |

Table 3.9 Plasma protein electrophoresis of the green iguana

| Parameters | Fractions (%) | Concentration (g/l) |

|---|---|---|

| Total protein | 100 | 74 |

| Pre-albumin | 6.62 | 4.9 |

| Albumin | 20.4 | 15.1 |

| Alpha 1 globulins | 0.02 | 2 |

| Alpha 2 globulins | 1.62 | 12 |

| Beta globulins | 18.91 | 14 |

| Gamma globulins | 35.13 | 26 |

| A:G ratio | 0.76 | 0.76 |

Results

Radiographic findings included increased radiodensity on the whole abdomen, compatible with the presence of fluid in the coelom

Radiographic findings included increased radiodensity on the whole abdomen, compatible with the presence of fluid in the coelom

Haematology analysis showed low RBC and low Hct, high WBC with slight toxic heterophilia

Haematology analysis showed low RBC and low Hct, high WBC with slight toxic heterophilia

Blood chemistry analysis showed elevated bile acids, GGT and total proteins. There was also low sodium

Blood chemistry analysis showed elevated bile acids, GGT and total proteins. There was also low sodium

Plasma protein electrophoresis showed low total protein and low albumin and increased A:G ratio

Plasma protein electrophoresis showed low total protein and low albumin and increased A:G ratio

Please evaluate the clinical history, Fig. 3.13a, b, the results of the physical examination and clinical diagnostic tests.

![]() 3. List your differential diagnoses.

3. List your differential diagnoses.

![]() 4. List your diagnostic strategy and possible diagnostic test.

4. List your diagnostic strategy and possible diagnostic test.

Diagnostic plan

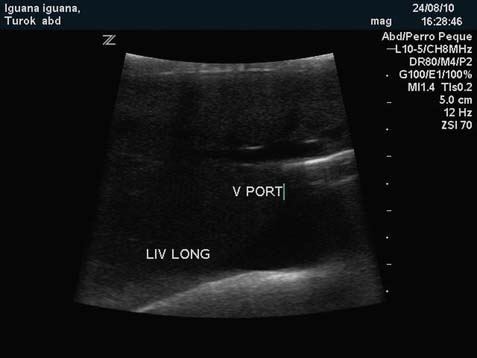

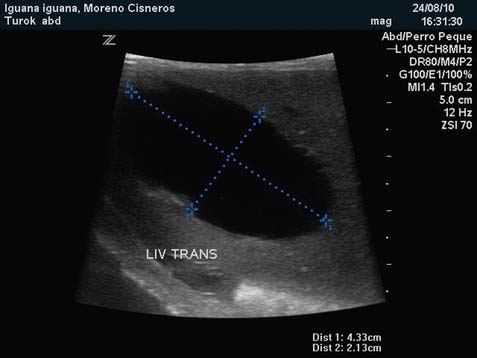

Results of the ultrasound study

There was free fluid in the coelom of the lizard

There was free fluid in the coelom of the lizard

Liver was enlarged and echogeneity of this organ is decreased being an image compatible with liver pathologies, such as cirrhosis or fibrosis

Liver was enlarged and echogeneity of this organ is decreased being an image compatible with liver pathologies, such as cirrhosis or fibrosis

The image and size of the gallbladder is abnormal, being huge and fluid-filled

The image and size of the gallbladder is abnormal, being huge and fluid-filled

The spleen is enlarged and with ultrasound image compatible with active infection

The spleen is enlarged and with ultrasound image compatible with active infection

Therapy

Because the iguana blood results were strongly suggestive of a generalized infection, a treatment with a broad spectrum antibiotic was started and exploratory laparotomy was suggested to the owners to get a definitive diagnosis. After an IO catheter was positioned in the right femur, fluid therapy was started in order to correct the ionic imbalances discovered in the iguana (Table 3.10).

| Ceftazidime 100 mg/ml | 200 mg/kg IM one dose every 2 days, 3 weeks |

| Butorphanol 10 mg/ml | 1 mg/kg IM SID 1 week |

| Fluids | Saline plus KCl 2 ml/kg/day IO IRC |

Surgery

The iguana was anaesthetized with an induction dose of alfaxolone 10 mg/kg. Rectal temperature, haemoglobin saturation, blood pressure and end tidal CO2 concentration were monitored during the surgical procedure (Fig. 3.18). After paramedial incision, 100 ml of ascitic fluid was eliminated from the coelomic cavity (Fig. 3.19). The ascetic fluid contained lower glucose levels than peripheral blood suggesting active infectious peritonitis. Four structures compatible with neoplasia masses or bacterial granulomas were found attached to the intestinal meso and to the mesovary; the four structures were surgically removed (Fig. 3.20). An exceedingly enlarged gallbladder containing 50 ml of bile was found during the exploratory laparotomy (Fig. 3.21). The bile was removed using a 60 ml syringe and total cholecystectomy was carried out (Fig. 3.22). The liver lobe surrounding the gall bladder was resected as well in the same surgical procedure (Fig. 3.23). The laparotomy was closed using routinely described techniques and the lizard recovered from anaesthesia uneventfully.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree