CHAPTER 130 Reproductive Management of White-Tailed Deer

Among deer, the whitetail is unique. Its reproductive timing can vary by as much as 6 months or more within the same hemisphere, it has a higher fecundity rate than most species of deer, it can reach puberty in its first year of life, and it can alter its fertility to meet favorable and unfavorable environmental conditions.

FUNDAMENTALS AND BIOLOGY

Puberty

Puberty can be reached as early as 6 months of age. Studies have demonstrated that, depending on nutritional conditions, up to 80% of doe fawns can conceive during their first year of life. Such rates have been common in the Midwestern farm belt.1 However, in the southeastern United States, this rate drops to an average of 40% or less.2 At the extremes of the range, puberty is generally delayed to the yearling age class. Nutrition is important and onset of puberty for fawns is dependant on body size. For northern races of deer, fawns must reach 80 to 90 lb, and for smaller southern races, body size of 70 lb or more seem to be required for puberty to occur in the first year of life.3 Both protein and energy are important. Protein is obviously critical to reaching minimum body size. However, it has been demonstrated that female fawns on high-energy diets had significantly higher levels of progesterone than did fawns on low-energy diets, regardless of protein levels in the diet.4

At the extremes of the range, whitetails may be programmed to delay puberty. Michigan researchers demonstrated that even when supplement-fed, doe fawns in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan did not become pregnant, whereas 60% or more of doe fawns in the farmlands of the Lower Peninsula commonly were pregnant.5

Seasonal Changes in Sexual Characteristics

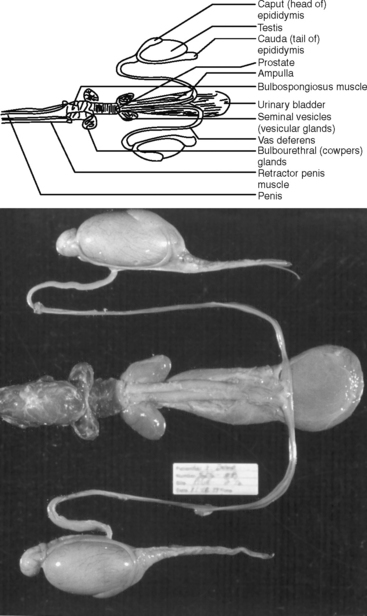

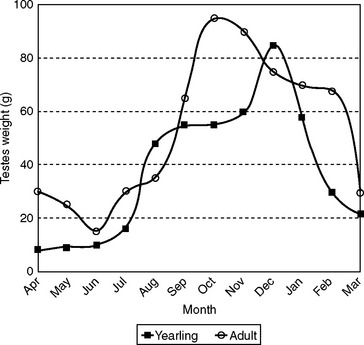

Changes in the reproductive anatomy of males are characterized by annual increases and decreases in secondary sex glands and the testes and epididymis (Fig. 130-1). These changes occur earlier in 2-year-old or older bucks than they do in yearling bucks (Fig. 130-2).

Fig. 130-2 Seasonal changes in testes weight of yearling and adult bucks.

(From Griffin RN: Characteristics and management implications of the male reproductive cycle of the white-tailed deer in Mississippi. Master’s thesis, Mississippi State University, 1980.)

Changes in female reproductive characteristics are less obvious than in males. Enlargement of the ovaries, vagina, and uterus do occur just prior to the rut. Changes are most pronounced in fawn and yearling does, but enlargement and increased elasticity are also noticed in the primary reproductive organs of adult females. The uterus of the white-tailed doe is bifurcate. Ovulation is said to occur from 12 to 14 hours after estrus.6 Implantation occurs about 30 days after conception.3 Following ovulation, normally from one to three corpora lutea are readily visible as ovarian swellings on one or both ovaries. Corpora albicantia of pregnancy are readily visible as large pigmented scars in formalin-fixed and sectioned ovaries of does for at least 3 months following parturition. Corpora albicantia of pregnancy from previous years are often visible as smaller pigmented scars in fixed tissue. Corpora albicantia from does not conceiving during their cycle are generally visible only as nonpigmented granular tissue in the ovaries for a few weeks following their formation.

Reproductive Timing

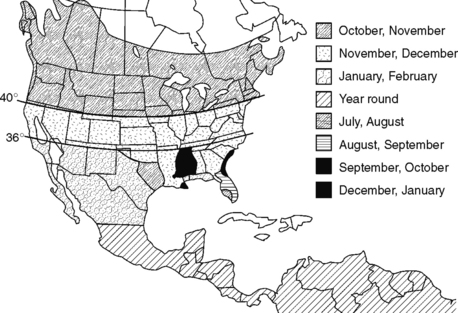

Breeding dates of the white-tailed deer change markedly across its range (Fig. 130-3). Initiation of the rut is photoperiod-related. This influence was illustrated most aptly by translocation of white-tailed deer from North America to New Zealand. Following translocation, reproductive activity of white-tailed deer including antler growth, velvet shedding, antler casting, and fawning all occurred about 180 days later than in the Northern Hemisphere.7 However, white-tailed deer also are known to have an endogenous circannual clock that can regulate reproduction in the absence of photoperiod cues.8 Genetics also is an important regulator, and different subspecies at the same latitude are known to have different rut timing. This difference can be as much as 2 months or more, and depending on the North American location, white-tailed deer have been documented to breed in every month of the year.9 The interrelationship of genetics and photoperiod was further shown by a study involving translocation of deer from Mississippi to Michigan and vice versa.10 In this study, deer shifted their reproductive patterns about 3 weeks earlier or later, depending on whether in Michigan or Mississippi. However, regardless of geographic location, the rut of Mississippi deer was about 7 weeks later than that of the Michigan deer. This genetic linkage was further confirmed by the crossbred offspring of these animals which, regardless of paternal or maternal lines, had intermediate rut timing between that of the two different parent lines.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree