CHAPTER 93 Reproductive Health Management Programs

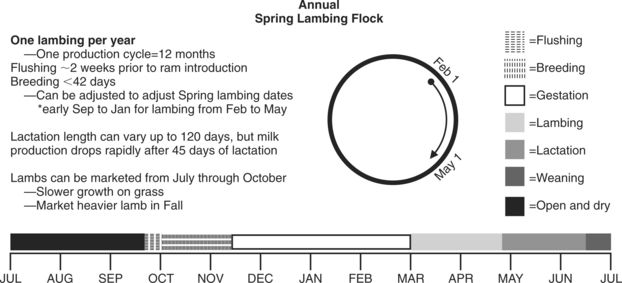

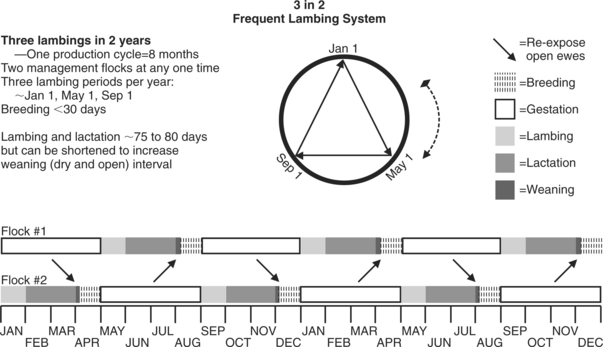

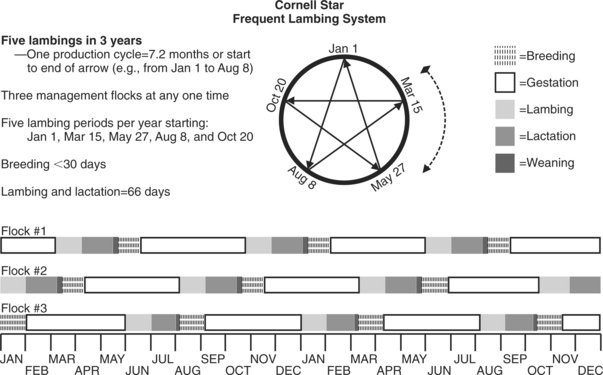

Throughout North America, many systems are used for managing sheep, from the traditional annual spring lambing with fall marketing of lambs off pasture, to managing several lambing groups per year, to marketing lambs year round. The basic principles for a reproductive health management program remain the same but need to be fine-tuned with each producer’s limitations and goals in mind.

SETTING GOALS AND MONITORING PRODUCTIVITY

The flock health cycle is composed of the following components:

It is a continuous process for which the backbone is monitoring and goal setting.

Record-Keeping Systems

An ideal sheep record-keeping system should have the following characteristics:

Information to Be Recorded

MEASURES USED IN REPRODUCTIVE MANAGEMENT

Body Condition Score

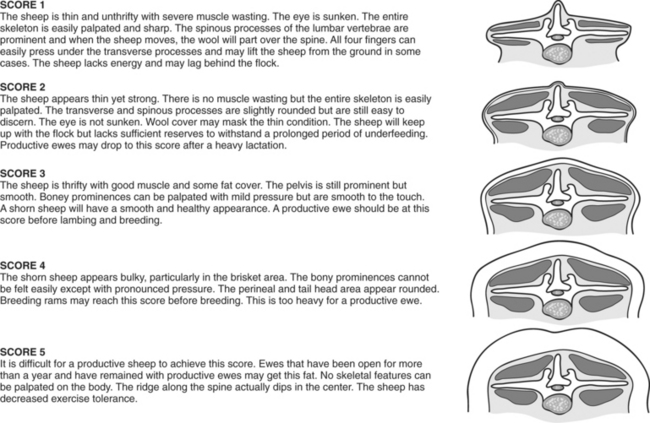

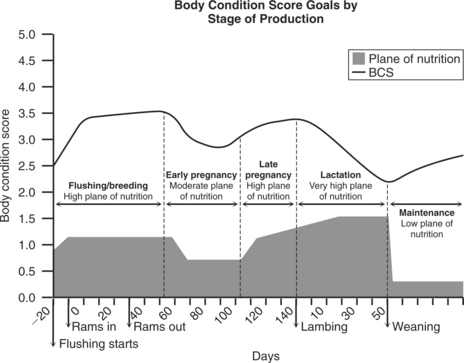

BCS is a subjective evaluation of muscle development and fat cover and is a management tool rather than an outcome measure of productivity. Routine scoring of ewes and rams helps the producer make nutritional management decisions. If BCS is used correctly, many nutritional mistakes can be corrected before problems begin. See Figure 93-4 for an overview of a commonly used sheep scoring system. Sheep need to be handled in order to be accurately scored because of wool cover and because of breed differences in muscling and fat deposition. A maternal trait/dairy-type ewe (e.g., Finnish Landrace, Rideau, Romanov) will not carry the lumbar muscling of a meat trait breed (e.g., Suffolk, Texel) and may carry more internal fat. Practice and understanding of breed differences will allow a producer to accurately score both types. Ideally, one operator should perform all the scoring, because correlation between different scorers was poor, but with high intraobserver repeatability, in a 1998 study by Calavas and associates (see Bibliographic References at the end of the chapter). The sheep should be palpated over the spinous and transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae, ribs, and shoulder and the muscles of the “twist” (hind legs and rump). This can be best done in a sheep race, with a drafting gate at the end to separate off the thin animals for special feeding. Goals for BCS and nutritional demands at the different stages of the production cycle are profiled in Figure 93-5.

Ram-to-Ewe Ratio

Factors used to determine the appropriate number of fertile breeding rams for the number of ewes include the age and experience of the ram (e.g., experienced versus maiden ram), ovulatory versus nonovulatory season, terrain (hill versus paddock), estrus synchronization in the ewe flock, length of ovulatory season of breeds being used, and fertility of those breeds during the nonovulatory season. Recommended ratios for common production situations are presented in Box 93-1.

Box 93-1 Recommended Ram-to-Ewe Ratios

With some highly fertile rams on range conditions, ratios of up 1:80 to 1: 100 have been used with success.

| Mature ram in breeding paddock | 1:40 ewes |

| Yearling ram in breeding paddock | 1:25 ewes |

| Mature ram with maiden ewes | 1:30 ewes |

| Mature ram on rough or barren terrain | 1:30 ewes |

| Mature ram in flock synchronized with ram effect (transition) | 1:20 to 1:25 ewes |

| Teaser ram used to synchronize flock (transition) | 1:40 ewes |

| Mature ram in synchronized flock in season | 1:15 to 1:20 ewes |

| Clean-up ram after synchronization (second cycle) in season | 1:30 ewes |

| Mature ram in synchronized out-of-season flock | 1:6 to 1:10 ewes |

Length of the Breeding and Lambing Period

The length of the breeding period—that is, period of exposure to the ram—will equal the length of the lambing season plus or minus approximately 3 days. Short, intense lambing seasons are useful for concentrating labor requirements, making more uniform feeding practices, and improving lamb survival. In season, the normal duration of estrus in sheep is 17 days. So a 42-day breeding period is sufficient to achieve excellent conception rates in cycling ewes exposed to capable rams.

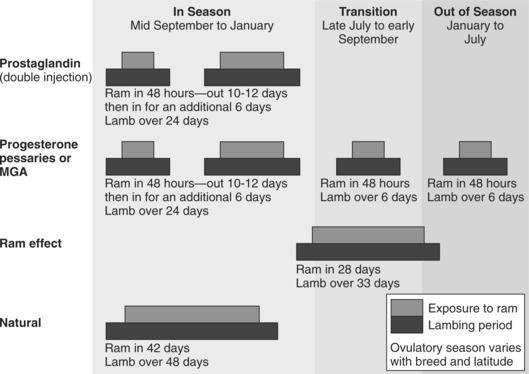

The practice of synchronization of estrus commonly is used to induce estrus during the transition period (3 to 6 weeks before the ovulatory breeding season), as well as out of season. Synchronization also can be used during the ovulatory season to shorten the breeding period even more. Figure 93-6 summarizes how the different methods of estrus synchronization can result in a tighter lambing period. If ewes are synchronized with sponges or prostaglandins in season, the breeding season will be 48 hours, optionally followed 10 to 12 days later with a clean-up ram for 6 days to catch repeating ewes. Out-of-season, synchronized ewes will have a breeding season of 48 hours.

MEASURES OF PERFORMANCE: CALCULATION, INTERPRETATION, AND GOALS

Calculating Measures of Performance

Flock productivity is measured by calculating either ratios, proportions, or rates. A ratio compares measures that do not share any animals (e.g., ram-to-ewe ratio). For both proportions and rates, the numerator is the number of sheep that are affected (e.g., lambed, culled, died, treated) and the denominator is the number of sheep that are at risk of being affected (e.g., to lamb, the ewe must have been exposed to the ram). A rate also requires a specified time period (e.g., day, month, year, breeding season, birth to weaning) during which the animals were at risk. For example, culling rate is the proportion of sheep that were culled in 1 year (as defined in Herd Health: Food Animal Production Medicine, edited by O.M. Radostits, p. 53; see Bibliographic References).

Reproductive Measures of Performance

The following parameters measure different aspects of reproductive performance. Not all measures should be used in any one flock. A variety are presented here because it is important that parameters be clearly defined, as well as the method of calculation. The language of measuring reproductive performance in sheep is variable and not as well defined as with dairy, beef, and swine performance (as discussed in Herd Health, p 107).

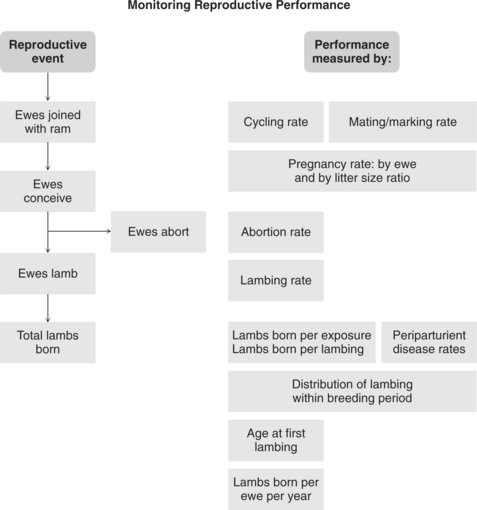

The goals reported here will vary greatly depending on the management system and breeds used but are appropriate for most North American conditions. A schematic of these parameters is presented in Figure 93-7. Possible causes of reproductive failure are summarized in Box 93-2. Data from a 1996 survey conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) (see Bibliographic References) are included where relevant. Table 93-1 summarizes data from Ontario flocks in the Sheep Flock Improvement Program and is useful for comparison with the USDA data.

Box 93-2 Causes of Reproductive Failure in Sheep

BCS, body condition score; eCG, equine chorionic gonadotropin; MGA, megestrol acetate.

Causes of Reproductive Failure in Sheep

| Ram Failure | Ewe Failure |

|---|---|

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|