CHAPTER 126 Reproductive Anatomy and Physiology of Male Wapiti and Red Deer

REPRODUCTIVE ANATOMY

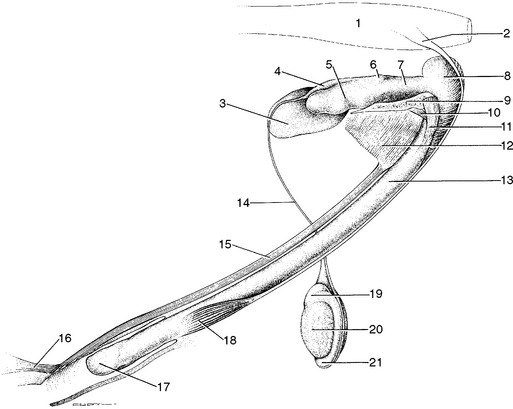

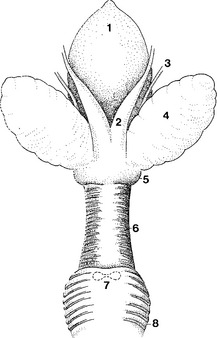

The reproductive organs of the male members of the genus Cervus consist of the testicles, epididymides, ductuli deferentia, accessory glands, and the penis and the prepuce1–3 (Fig. 126-1). The testicles are located in a dependent scrotum between the hind legs.

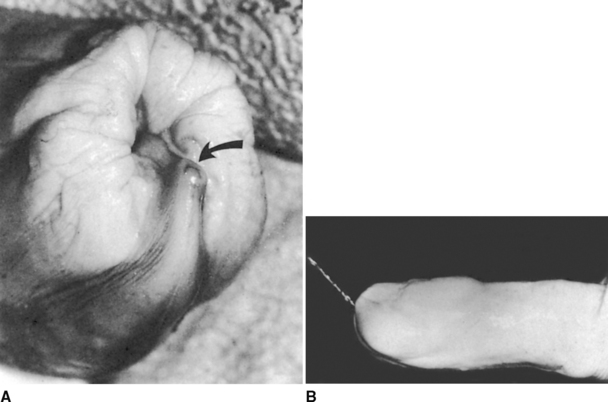

The penis is a fairly simple rod-shaped structure that undergoes very little increase in circumference during erection, but increases in length by about 40%.1 There is no sigmoid flexure (see Fig. 126-1). The urethra, which lies on the ventral surface of the penis through its length, curves dorsally at its extremity, and permits the ejection of urine and a few sperm cells in an upward direction, which is important during “thrash-urination” activity indulged in by rutting males as they spray upward almost at right angles onto their ventral abdomens, neck, and throat1 (Fig. 126-2).

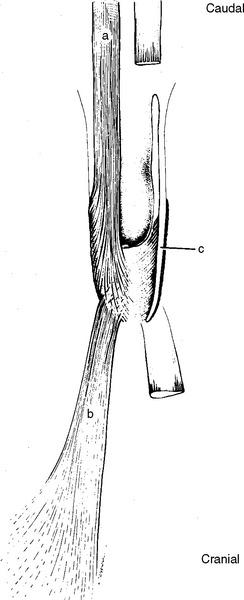

The prepuce has well developed muscles that are responsible for the remarkable rapid forward and backward movement, often called palpitation, of this region seen during the rut1 (Fig. 126-3). This behavior, and the degree of development of these muscles, has not been reported from any other genus.

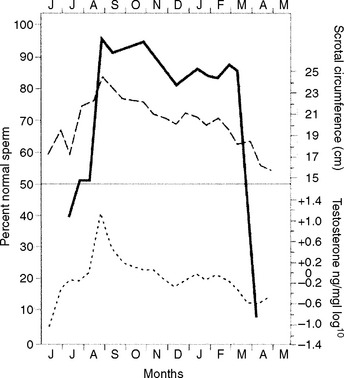

Scrotal circumference increases markedly and peaks at about the time of the onset of the rutting season. A three-fold increase in size between early summer and autumn has been noted in red deer stags, and the scrotal circumference of male elk increases by about 50% during this period4 (Fig. 126-4). After this it declines fairly steadily until it reaches its nadir in spring.4 The percentage of normal sperm in ejaculates, the scrotal circumference, and the concentrations of serum testosterone undergo annual changes in synchrony.4

Cellular changes in the testis and the production of spermatozoa occur seasonally. As testosterone levels rise after the summer solstice, activity within the testicular parenchyma increases. The diameter of seminiferous tubules increases and the development cycle of seminiferous epithelium occurs. As these events take place, so the testicular size changes.2,4

At the onset of the rut, the interstitial cells of the testis are of maximum size and number, as is the activity of the seminiferous tubules. When reproductive activity has ceased, in the spring at about the time of antler casting, the interstitial cells are small and inactive, no mature spermatozoa are visible in the lumen, and the cells of the seminiferous epithelium show almost no differentiation beyond the very earliest forms of sperm precursor.1,2 These changes are reflected in the measurements of scrotal circumference (see Fig. 126-4). Thus, the stag undergoes testicular and hormonal changes similar to puberty on an annual basis.

The epididymis also undergoes seasonal changes. In autumn it is lined by a tall pseudostratified columnar epithelium. By spring the height of this epithelium declines sharply and the nuclei of the epithelial cells are condensed. In autumn the cauda epididymidis is densely packed with sperm. In early summer no sperm are visible in the lumen.1,2

Accessory Glands

The accessory glands include paired ampullae, paired vesicular glands, both a body and disseminate part of the prostate, and small bulbourethral glands3 (Fig. 126-5).

At their distal ends the ductuli deferentia enlarge to form the ampullae. These organs lie in close apposition to one another throughout most of their length in a common bundle of connective tissue. They are 4 to 5 cm long and about 1 cm in diameter at their widest in wapiti. Each ampulla opens separately into the duct of the adjacent seminal vesicle, forming short ejaculatory ducts.3 Their epithelium exhibits changes that are correlated with the sexual cycle. Histologically the ampullae have the appearance of a branched tubular gland with sac-like dilatations, the crypts of which contained secretion. In May the epithelial height has not changed, but the nuclei have condensed. At this time some crypts contain densely packed degenerative sperm.1

The paired seminal vesicles are attached to the anterior end of the pelvic urethra, lateral to the ampullae, and are joined medially by a genital fold. They are 6 to 7 cm long and have a slightly lobulated appearance.1 In autumn they contain a thick yellow secretion. Each gland opens separately into one of the paired ejaculatory ducts. The glands show increased epithelial height from July into the rutting period in October. They regress by November and contain little or no secretion in spring.1,2

The prostate gland consists of two parts. It has a discrete, bilobed body lying anterior to and continuous with the disseminate prostate. This body is visible on the dorsal part of the pelvic urethra as two small discrete hemispherical masses just caudal to the ligamentous band that connects the vesicular glands. It opens ventrally into the pelvic urethra. The epithelium of the prostate body is of a tall, columnar type during the rut and shortens markedly, appearing cuboidal by November.1,2 The disseminate part of the prostate can be identified throughout most of the pelvic urethra, underlying the urethral muscle. It has numerous ducts opening into the urethra.1 There appears to be little seasonal change in epithelial height.1,3

The bulbourethral glands are extremely small, the combined weight being 0.6 g in wapiti. They are found at the junction of the urethral and bulbourethral musles under a layer of connective tissue on either side of midline. In one study comparing epithelial heights before and after the rut, no differences were found.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree