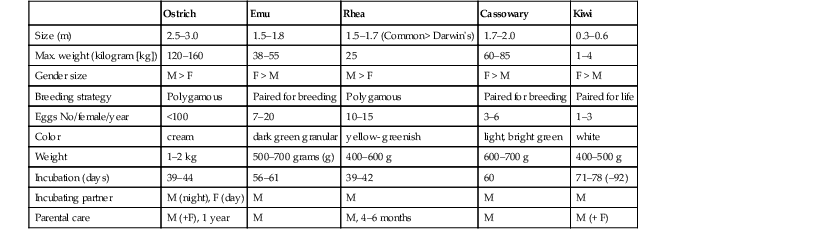

Maya S. Kummrow Ratite is not a strict taxonomic term; it is used to refer to flightless birds that do not have a keel but have, rather, a flat “raft-like” breast.2,19 In general, ratites are classified in one order, Struthioniformes, with four suborders with distinct geographic distributions: (1) Struthiones are endemic to the African continent (apart from introduced populations in Australia), (2) Rheae in South America, (3) Casuarii in Australia and New Guinea, and (4) Apteryges in New Zealand.19 Struthiones include one family, Struthionidae, and one species with currently four recognized subspecies: (1) the North African ostrich (Struthio camelus camelus), (2) the Somali ostrich (S. c. molybdophanes), (3) the Massai ostrich (S. c. massaicus), and (4) the South African ostrich (S. c. australis).19 Many farm populations (S. c. domesticus) are hybrids of various subspecies. Although ostrich farming became well established on the African, American, European, and Australian continents in the second half of the 20th century, wild ostriches have become exceedingly rare in some parts of their range. South Africa and East Africa still hold strong populations, but most of the S. c. camelus subspecies populations in West and North Africa are considered endangered.14,19 The Rheidae, the only family to the suborder Rheae, are endemic to the Neotropical Region and include two species: (1) the Common or Greater Rhea (Rhea americana) and (2) the Darwin’s or Lesser Rhea (Pterocnemia pennata). Although neither species is reckoned to be in immediate danger, both have been listed as near-threatened, and their numbers are declining in most parts.19 The close genetic relationship between the families Dromaiidae (emus) and Casuariidae (cassowaries) is recognized by the common suborder Casuarii. Emus consist of one single species (Dromaius novaehollandiae) and occur in stable populations on mainland Australia, and the cassowaries constitute three clearly distinguishable species (Southern cassowary, Casuarius casuarius; Dwarf cassowary, C. bennetti; Northern cassowary, C. unappendiculatus), with a high number of subspecies.19 All three species occur in altitudinally separate habitats in New Guinea, and the Southern cassowary also occurs in the northern parts of Australia. Because of defragmentation and reduction of their rain forest habitat, cassowaries are considered endangered.19,41 The fifth ratite family, the kiwis (Apterygidae), is endemic to New Zealand and consists of three species (Brown Kiwi, Apteryx australis; Little Spotted Kiwi, A. owenii; Great Spotted Kiwi, A. haastii). Habitat destruction, inadvertent poisoning and trapping for pest control, and introduced predator species have greatly reduced their numbers and rendered some populations endangered, but because of their reclusive way of living, their status is poorly known.29 Whereas emus occur in a wide variety of habitats, ostriches prefer open semi-arid areas with short grass and are well adapted to hot and dry environments.14,18,19 Rheas are characteristic to the semi-arid tall grass steppe and other savannah-type habitats of South America, but they like the vicinity of water or wetlands for breeding.19 Cassowaries and kiwis are most typically found in rain forest habitats,19,41 but because of destruction of habitat, kiwis are also to be found in other habitats with relative high humidity, adequate soil texture, and density of vegetation to dig their burrows. All ratites may swim.19 Ostriches and rheas are gregarious, diurnal birds, with males being territorial and entertaining polygamous social structures during breeding season.14,18,19 Emus are usually found alone or in pairs except when they form large groups on the move or in places where water and food are abundant. Cassowaries are shy, solitary, and territorial all year round, with a mostly crepuscular activity pattern. Kiwis are almost entirely nocturnal, take refuge in earth burrows during the day, mate for life, and show strong attachment to their territory.19 Except for the kiwi, the ratites are the largest birds in the world (Table 9-1). Ratites lack a keel, and as the need for flight is absent, ratites lack clavicles (except emus) and triosseus canals, the thoracic girdle is modified by fusion of scapula and coracoid, and the only pneumatized bone is the femur in ostriches and emus. The wings are vestigial and carry variable numbers of claws (two in ostriches, one in rheas, none in emus and cassowaries) and are used for balance and display behavior. Ratites have long, heavily muscled legs, which enable them to run at high speeds; they also use their legs for defense and offense, kicking forward, with cassowaries using both feet at once. Ratites lack a patella. Whereas emus, cassowaries, and rheas have tridactyle feet with a nail on all toes, the ostrich only has two toes (didactyl) with a nail on the larger, medial toe only. Cassowaries carry a daggerlike, dangerously sharp claw on the inner toe. Kiwis have a small fourth toe pointing caudally with a spurlike nail.18,19,52,53 In ratites, the barbules, although present, do not interlock, giving the ratite feathers the particular fluffy appearance sought after for decoration and fashion.18,19 Feathers of the emu and cassowaries have a double shaft.53 Down feathers are rare or absent, and ratites continuously molt. The plumage of kiwis has a shaggy appearance because of the hard, hairlike, waterproof distal ends. Cassowaries have a unique protuberance on the head, called casquet or helmet. Brightly colored wattles are only present in the Northern and Southern species and likely function as a social signal.19,41,53 The respiratory system in ratites is comparable with that of other avian species with 10 air sacs.6,7 In the emu, the complete cartilaginous tracheal rings in the distal trachea are interrupted by a 6- to 8-cm long ventral cleft, where a thin membrane forms a large, expandable pouch to produce the characteristic booming sound.19,52,53 Respiration rates of ostriches fall within two ranges, either within a low range of 3 to 5 breaths per minute (breaths/min) or a high range of 40 to 60 breaths/min when panting in response to heat stress.53 Ratites have a slightly lower core body temperature compared with other birds; kiwis, especially, have a low average basal temperature of 38° C, approximating that of mammals.47 All ratites lack a true crop, but considerable differences exist in the musculature and enzyme secretory function of the gastric compartments and characteristics of the intestinal tract, reflecting adaptations to different diets.18,52,53 Having adapted to a rough, fibrous diet, both ostriches and rheas rely on a small glandular patch in the proventriculus but show a large, thick-walled ventriculus with a distinct koilin layer. Other than in the rhea, in which the proventriculus is significantly smaller than the ventriculus, both compartments are similarly sized and connected by a large, rather indistinct sphincter in the ostrich and small stones for grinding are physiologically found in both compartments. Ostriches show a unique arrangement of the two gastric compartments, with the thin, saclike proventriculus taking a turn and the gizzard being located cranioventrally. Whereas the rhea largely depends on enormous paired ceca for effective hindgut fermentation, the ostrich has a particularly voluminous colon and long rectum and relatively smaller ceca. Spiral folds within the cecal lumen provide an increased surface area for fermentation. Following the adaption to a more nutritive and less fibrous diet, the proventriculus in emus and cassowaries is comparably large and diffusely glandular, whereas the small ventriculus is thin walled and lacks a koilin layer altogether in the cassowaries. The paired ceca in emus and cassowaries are vestigial and of minor functional importance, particularly in the cassowary. The gastrointestinal (GI) passage time is approximately 48 hours and 18 hours in ostriches and rheas, respectively, but only 7 hours in emus.53 In all ratites, a particularly strong rectal–coprodeal sphincter results in separate defecation and voiding of urine: feces are stored in the rectum, whereas urine is mainly stored in the proctodeum, which acts as “bladder.”18 Ratites lack a true bursa; instead, the bursa of Fabricius in the ostrich and emu forms an integral part of the dorsolateral wall of the proctodeum. No gallbladder exists in the ostrich, but one is present in the other ratites.53 Male ratites have an intromittent reproductive organ. In adult ostrich males, the flaccid phallus is up to 20 cm long and lies folded in a phallic pocket in the ventral wall of the proctodeum; when erect, it may reach a length of 40 cm and physiologically deviates to the left.18,53 It serves to transport sperm via a dorsal sulcus (in the ostrich and kiwi) or a central cavity (in the rhea, emu, cassowary) but has no urinary function.53 Manual gender determination may be easily conducted in young birds at 1 to 3 months: the clitoris and the phallus are similarly sized but differ in shape and in the presence of the seminal groove.18 Female reproductive organs are similar to those of other avian species; usually only the left ovary and oviduct develop.53 Kiwis, however, are among the very few avian species with paired ovaries.29 Although the larger ratites have acute eye sight,53 the nocturnal kiwi mostly relies on its strong sense of smell with its nostrils at the distal tip of the beak and excellent hearing, as evidenced by large earholes. Kiwis lack a pecten, and their vision is rather poor.19 Ostriches and, to a lesser extent, emus and rheas are reared as farm animals for meat, feathers, and hides in Africa, Europe, Australia, and South and North Americas.18,19,52 Ostriches and rheas may be kept in large groups; however, during breeding season, males become territorial, so harem groups are advisable.18 Emus are usually kept in pairs. In zoologic institutions, ostriches, rheas, and emus are commonly included in multispecies exhibits with other herbivores. In the wild, ostrich groups move and feed with herds of hoofstock, but they tend to avoid close contact with other animals. If startled or challenged, ostriches may react with panicky escapes; therefore, exhibits need to provide sufficient space and structures to allow avoidance or flight behavior. Barriers have to be easily visible, as ostriches, emus, and rheas tend to get entangled and caught in piles of branches, wires, and dry moats. Large ratites are usually kept in open paddocks and fenced pastures.18 Ratites need indoor enclosures or at least dry shelters to be protected against wind and precipitation. They may tolerate cold temperatures and even snow for short periods, but they are sensitive to cold-wet conditions.45 As waterproofing is impossible because of the lack of interlocking barbules, ratites get sodden in rain, and they lack down feathers for insulation.19 Indoors areas with heated or at least well-insulated flooring are imperative for hatchlings and juveniles.18 Cassowaries may also be kept in pairs and may tolerate each other, but it is advisable to keep them separate for incubation of the eggs and rearing of the chicks.23,41 Keeping kiwis in captivity is not easy; usually, only the Brown Kiwi is kept in zoologic institutions but is very rarely bred. Kiwis are to be kept in pairs as they take mates for life. Deep earth floors for burrowing, high humidity, and dense vegetation are important factors in their exhibit.19 Ostriches and rheas are exclusively vegetarian and selective grazers with very efficient fiber utilization in postgastric microbial fermentation. Green annual grasses and forbs are preferred, although leaves, flowers, fruit from succulent and woody plants, and, rarely, insects and small invertebrates are also consumed.18,19 Because of the economic interest in ratite farming, a large body of information on the nutritional requirements of ostriches is available. Complete diets are commercially available in pelleted form, which should be supplemented with high-quality roughage and vegetation for adequate fiber intake and enrichment.13,52,53 Having adapted to an arid environment, absence of drinking is possible in adult ostriches, rheas, and emus if succulent food is fed, but reduced weight gain and impaired reproduction are often caused by inadequate water supply.19,52 Emus are omnivorous but show a highly selective behavior for nutritious food items. In the summer time, a large part of their diet consists of insects.19 Cassowaries are largely frugivorous but may also consume fungi, insects, and small vertebrates.41 Wild kiwis consume almost exclusively invertebrates from the forest floor, but their captive diets are generally meat and fruit, with much higher carbohydrate and water content and lower crude fat compared with the diet in the wild.19,39 While chicks and kiwis may easily be restrained manually, catch pens or chutes are most appropriate for adult, large ratites. Ratites jump, kick, and slash in a forward direction; therefore, manual restraint of large ratites may be dangerous and requires experienced personnel.47,52 The risk of injury from the daggerlike claw does not allow for manual restraint of adult cassowaries.47 Ostriches, emus, and rheas may be approached from behind or the side. At least three people are needed to handle an adult bird, but care needs to be taken not to grab the bird by the neck (neck hooks are not recommended), the legs, or the vestigial wings or to interfere with respiration during straddling.47,52,53 In ostriches, lowering the head quickly to the ground prevents them from kicking, and they may even assume sternal recumbency. Darkness has a calming effect on ratites, and hooding is one of the best aids to handle manually restrained ostriches.52 Other ratite species are less tolerant of hooding, and the effect is unpredictable.53 As ratites are prone to exertional myopathy, chemical restraint is advisable for any longer procedure to reduce stress and risk of injury to birds and handlers.52 Whereas most other birds and chicks are not recommended to be fasted for anesthesia, adult large ratites may be fasted for 12 to 24 hours and water withheld for up to 4 hours prior to anesthesia to reduce the risk of regurgitation and aspiration.42,52,53 Chicks and kiwis are usually just manually restrained for induction via face mask and maintained, ideally intubated, on isoflurane inhalation. For remote injection of anesthetic drugs in larger birds, the ideal dart placement is perpendicular into the proximal thigh muscle.53 Underdosing may result in overexertion during the excitatory phase and should be avoided. Benzodiazepines (diazepam or midazolam 0.3 to 1 milligram per kilogram [mg/kg]) and α2-agonists (xylazine 0.2 to 3 mg/kg, medetomidine 0.05 to 0.5 mg/kg) are commonly used alone or in combination with butorphanol (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg) for sedation and premedication, but times to effect and efficacy are highly variable and depend on the disposition of the bird.42,52,53 Ketamine (3 to 20 mg/kg) or telazol (2.3 to 4.9 mg/kg) are commonly used as induction agents but need to be combined with benzodiazepines or α2-agonists to prevent muscle rigidity and rough induction and recoveries.47,53 Injectable agents rarely provide anesthesia of sufficient duration for longer procedures, and inhalants (usually isoflurane) are commonly used for maintenance.42,52,53 Intubation is achieved easily with the tracheal opening readily visible at the base of the tongue.47 The unique tracheal cleft in emus necessitates wrapping of the lower neck with an elastic bandage to avoid insufflation of the pouch.47,53 Alternatively, intravenous (IV) maintenances on a triple-drip combination (ketamine, xylazine, and guaifenesin) or propofol infusion are described in the literature.47 Ratites appear rather refractory to the sedative effects of potentiated opioids but show excessive running or frenzied activity during the excitatory phase and apnea during anesthesia.47 However, combinations of thiafentanil, α2-agonists, and telazol have shown promising results in emus and rheas.6,17,38 Monitoring via pulsoxymetry is possible on the ulnar vein or intermandibular tissue.47 Supplementation of vitamin E or selenium, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and adequate infusion therapy may be advisable to prophylactically address exertional myopathy.47 Recovery should occur in a dark, padded room, or the birds need to be supported until they are able to maintain normal head position. Sternal recumbency is not a problem, but lateral recumbency over a long time might result in peroneal nerve paralysis, so careful padding is crucial.53 A body wrap may help to control the recovery process.52 Haloperidol administration achieved long-term sedation in adult ostriches for transport and reduction of aggression, lasting for 20 hours.38 For short transports, azaperone is useful as it provides little muscle relaxation but good tranquilizing effects for up to 24 hours.47 One of the most commonly described surgical interventions in ratites is proventriculotomy to address gastric impaction and ingestion of foreign bodies.3,33,52,53 Juvenile ostriches are most commonly affected, but cases in juvenile rheas and an adult kiwi have been reported.24,25 The proventriculus in ostriches is palpated in the left paramedian quadrant over the xiphoid. A left lateral approach over the proventriculus is preferred. Failure to adequately absorb the yolk sac may necessitate removal of the yolk sac in chicks, which is usually performed with a ventral midline approach, cranial of the umbilicus to beyond the extension of the yolk sac.52,53 After excising the umbilical cord, the yolk sac is lifted out of the coelomic cavity and the duct ligated. Any spillage of yolk requires vigorous rinsing with warm saline. As in all other birds, egg binding may have to be addressed surgically, and castration of male ratites has been performed successfully.18,53 Wound management and orthopedic surgery are commonly necessary, as traumatic injuries are frequent in ratites.52,53 These procedures follow the same principles as in any other species, considering the requirements to support heavy weights and bipedal locomotion in these large and rather nervous animals.52

Ratites or Struthioniformes

Struthiones, Rheae, Cassuarii, Apteryges (Ostriches, Rheas, Emus, Cassowaries, and Kiwis), and Tinamiformes (Tinamous)

Ratites

General Biology

Unique Anatomy

Special Housing Requirements

Feeding

Restraint and Handling

Surgery

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ratites or Struthioniformes

Chapter 9