CHAPTER 2  PSITTACINE BEHAVIOR

PSITTACINE BEHAVIOR

Introduction

Members of the order Psittaciformes are the most commonly kept pet birds worldwide. The bond between humans and psittacines is centuries old. The existence of over 300 species of Psittaciformes and their wide variations in behavior emphasizes that we have knowledge of a mere fraction of the significant behavioral parameters of these birds. Despite this paucity of information, the keeping and breeding of psittacines in captivity is likely to continue to expand. With the decimation of habitats worldwide, captive reproduction of many species has become the route to ensure survival of these species.

For a compelling and inclusive treatise on the need for a cohesive approach to avian behavior, along with more than 1400 references regarding individual studies, the reader is strongly encouraged to read Kavanau’s Behavior and Evolution.20

Wild Bird Behavior

As stated in the introduction, although thousands of articles have been published on various aspects of psittacine behavior in the wild, what is unknown still far exceeds what is known. The development of ethograms for most parrot species has not been accomplished. An ethogram is a systematic behavioral inventory consisting of (1) a detailed list of all behavioral elements that occur in a given context and (2) guidelines for definition of and discrimination among those elements. The nature of the observations required, specifically tracking individual birds for prolonged periods of time, is daunting. Detailed chronologic records would need to be obtained relating to parent and sibling interactions, interactions with conspecifics of various ages and relationships, play behavior in juvenile birds, and the development and maintenance of pair bonds. This research, if and when accomplished, would identify various wild behaviors but not necessarily elucidate their functions.

Many studies are intrinsically fascinating but have no direct application or concrete interpretation at this time.3,4,19,20 Disagreements among researchers about general theories and terminology complicate the documentation and advancement of psittacine ethology. Studies of captive populations of psittacines have yielded fascinating data, but the captive environmental context may alter the results from what would occur in nature.

Species Differences

Nomadic psittacines (such as many Australian species), which by definition migrate in order to find sufficient food and water, have evolutionarily developed significant differences in their social and individual behaviors when compared with birds in tropical climates (such as South American macaws and Amazons), where food supplies are more consistently present within a localized area. For example, nomadic species (budgerigars, lovebirds) tend to be colony breeders. This adaptive survival mechanism serves them well. The larger number of individuals in these flocks provides protection from predators and increases the efficiency of foraging. Socialization, therefore, tends to be less pair specific, and fewer confrontational dominance displays occur. Not surprisingly, these large-flock nomadic birds learn more readily from conspecifics—for example to consume new food items—than do South American species.29

Time Allocation and Behaviors

The percentage of waking hours spent performing the following major categories of behaviors has been averaged from the sources cited (Box 2-1). These were quantified when birds were not at nest, although some studies did involve degrees of courtship or territoriality that may indicate peribreeding behavior.

Vocalization

The range of vocalization in birds is extensive, and they can discriminate and identify individual songs and cries in order to interpret conveyed information. Evidence from studies conducted in disparate disciplines indicates that the left and right hemispheres of the brain in avian species have asymmetric functions; specifically, as in humans, the left brain is markedly dominant in the learning and reproduction of vocal communication (i.e., “song”) in birds.31

Unrelated newly hatched budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulates) produce comparable vocalizations. However, by 3 weeks of age their cries have been shaped to mimic those of their parents.4 Mutual vocal recognition of chicks and parents is universal. Parents equidistant from their own young and those of conspecifics will react frantically to distress calls by their offspring while ignoring the calls of others. Likewise, cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus) chicks in the nest will respond to the song of a parent bird outside their field of vision but not to that of other adult cockatiels.

Amazons in contiguous regions of Central America have been determined to have regional dialects. Individual birds in adjacent areas can vocalize and recognize both dialects.31

Extensive studies of avian neurology and neuroanatomy have shown it to be unlikely that birds that are not conspecifics can fully “understand” vocalizations of other species, although mimicry is obviously within the ability of many birds. The strength, duration, and timing of song in conspecific birds located in temperate climates vary significantly from birds in tropical climates. The potential significance of these differences is still controversial.20,31,40

Body Language

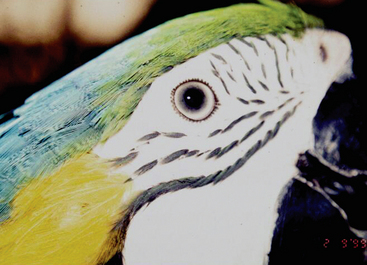

Posturing is used to display various messages to conspecifics. Territoriality and breeding behavioral displays, including filoerection, voluntary pupillary constriction and dilation, fanning of tail feathers, spreading of the wings, and beak lunging are all noted in captivity as well as in nature. It is likely that, in addition to recognizing these overt behaviors, humans do not fully recognize more subtle body language displays and the messages they are intended to convey (Figures 2-1 and 2-2).

Foraging Behaviors

Natural foraging habits of birds have several ramifications in captivity:

Intraspecies Contact and Species Variations

Cockatiels engage in extensive head preening as part of their pair-bonded and parent-offspring interactions. However, this preening can take on an aggressive component. Adult birds (usually males) will “preen” the female’s head to get her to move from the nest box. This preening can turn into pecking if the preening hint is not taken.20 Most veterinarians have noted the tendency of some parent cockatiels to overpreen, pluck, or damage the heads of baby cockatiels in the nest.

Conversely, adult cockatiels tend to avoid body contact with conspecifics, startling readily if they accidentally touch another bird. This contact avoidance is present in most psittacine species.30

Compare this with Peach-faced Lovebirds (Agapornis roseicollis), which tend to enjoy “huddling” not only as young in the nest but also as adults. In lovebirds, extensive body contact may be seen at all ages. Lovebirds are much less aggressive with their preening; males will often (when the female is in the nest box) preen the female all over her body without becoming aggressive.20

Parenting

Although the exact conditions of chick development in the wild are unknown in most species, many critical developmental factors can be assumed from watching captive-raised birds and from knowledge of development in other species. The visual, tactile, and auditory development of birds in nature is greatly influenced by interaction with parents and siblings. The ontogenetic comparisons of development in parrots seem to correlate more closely with those of the great apes than they do with those of dogs and cats.39 The importance of weaning and fledging in wild psittacine development may contribute to the plateaus in learning that occur in captive-tested psittacines.31

Captive Psittacine Development

The typical psittacine breeding facility has advanced in recent decades to meet many of the physiologic needs of neonatal birds, including regulation of temperature, humidity, and improved nutrition in the form of formulated hand-feeding diets. The acclimation of our birds to physical contact and handling has been part of the hand-raising process and generally produces a bird with more attachment to and positive interaction with people, at least initially. However, the emotional and social development of these birds is undoubtedly affected by the lack of conspecific interactions comparable to those that would occur in nature. Unacceptable and exaggerated behaviors such as feather destruction, excessive screaming, and biting have manifested in a large percentage of our current population of hand-raised pet psittacines. These behaviors are generally not noted in wild-caught pet psittacines or those captive-bred but allowed to be raised by the parents. These behavioral abnormalities have been postulated to be similar to the “orphanage syndrome” or relative attachment disorder described in human children deprived of affection and stability in their early months and years of life. Such behavioral abnormalities in children (and also those in human-raised psittacines) often do not manifest until later in life.22,23,50

Allowing the parents to incubate and raise their chicks creates potential financial and emotional liability for psittacine breeders. Broken eggs, abused or neglected chicks, and accidental injury can all occur when chicks are left in the nest. However, little doubt exists that this is the ideal environment for emotional and social development. There also are physical advantages to development within the nest box, as a study conducted on Dusky Pionus parrots (Pionus fuscus) demonstrated. Between 16 and 45 days of age, when bone growth is rapid and the skeletal structure still weak, chicks housed separately in incubators stumbled about, apparently in search of sibling or parental contact. Clutches maintained together huddled closely and moved little, and this huddling aided in supporting the appendicular skeleton.15 Additional studies have shown increased bony deformation and osteodystrophy in chicks housed individually in incubators. Fortunately, increasing numbers of breeders are now allowing the parents to incubate, hatch, and raise the chicks through fledging.

Human interaction with the chicks can begin either in the nest box (known as co-parenting) or after the chicks have fledged. In this way, young birds become acclimated to human handling by brief daily interactions while still benefiting from parental and sibling interaction. Ongoing work at the University of California, Davis has shown the benefit, at least in Orange-winged Amazons (Amazona amazonica), of handling the young on a regular basis while still allowing parent rearing of the chicks. In some species and individuals, interaction with humans may increase the risk of abuse or neglect by the parents, so this technique will not be applicable in all situations.

If it is necessary to hand-raise a psittacine chick, every attempt should be made to meet the physiologic and psychologic needs of that individual. Lack of concrete data regarding the exact nature of these needs leaves us with a duty to replicate the environment and interactions provided in the wild. This includes body pressure; warmth and contact; a dark, safe, secure nest box area; feeding on demand; the ability to incrementally explore the nest environment; and visualization of the outside world without physical exposure. Phoebe Linden has labeled these aspects of neonatal and juvenile psittacine developmental care, along with specific feeding techniques and materials, as Abundance Weaning.22–25 Readers are urged to review this material in order to properly understand and inform their clients of the necessity for initial and ongoing developmental enrichment.24

Socialization

As stated previously, there likely is a window of time in early development during which exposure of psittacines to various species (conspecifics, other birds, humans, other household pets) and objects results in acceptance of these, or minimally in a reduction of fear and avoidance. Lack of exposure to conspecifics during this time may prohibit normal development and the potential for successful pair-bonding.41 Substitution of the human caregiver for the parent, sibling, and/or mate occurs in many captive psittacines.

The same phenomenon is documented with captive-raised birds of prey.18,30 Intensive socialization during hand-raising of falcons and hawks creates a bird that is less readily disturbed by the presence of civilization (humans, vehicles, hunting dogs, and so on). This imprinting on people is also used to encourage mating with humans who have been equipped with semen collection devices (hats or other designs) for later use in artificial insemination of pure and hybrid falconry birds. However, removing the fear of humans increases the potential that the normal territoriality of mature raptors may be violently directed at any humans invading this territory. Again, as in psittacines, certain species seem to be more prone to territorial aggression.18

Stimulation

Stimulation is similar to socialization but does not require an individual (person or animal) to interact with; it instead connotes experiences or situations. Generally, the more numerous and varied the stimuli to which a bird is exposed at a relatively young age, the less likely it is to develop fears of these objects, noises, or phenomena (Figure 2-3). The ability to retreat from overstimulation via a hide box should be provided, especially for the young but also for adults.

Consequences of Inactivity

The absence of normal stressors in a safe, clean, stable captive environment is often the main cause of problem behaviors such as feather destructive behavior or stereotypy. In fact, these “problem” behaviors are typically displaced and/or exaggerated normal behaviors. A common presentation to veterinarians is the bird owned by a loving, attentive, conscientious owner who provides a clean and stable environment, constant access to sufficient food and water, and multiple toys. These owners are particularly distressed when their bird initiates feather destructive behavior, and they believe that the bird must be lacking some comfort or necessity. In fact, the opposite is often true. These birds are secure and all their needs are met without the expenditure of any physical or mental energy. They therefore have no mental or physical stimuli—no need to forage for food, guard against predators, seek shelter, attract or keep a mate, locate nesting areas, or provide for offspring. It follows that, of the natural behaviors remaining, one such as preening may then assume a dominant role and be accelerated to an abnormal degree. There likely is also a similarity to the phenomenon seen in people with autism—a need for stimuli, albeit negative stimuli, in an environment devoid of any natural challenges often results in hair pulling or self-mutilation.

Toys

Depending on the individual bird, toys may be useful displacers for mental and physical excess energies.27 Varieties of toys are available, and these can serve multiple purposes. Objects such as old telephone books provide an outlet for the need to chew and mechanically dispel excess energy. Puzzle toys (with a food treat or other object that is revealed and obtained after manipulation) provide both physical and mental stimulation (Figure 2-4). However, the ability and desire to interact with toys is not universal and may be learned to some degree. Seldom will the instillation of toys into the environment substitute for human interaction and training.

Behavior Modification

Exaggeration of Normal Behaviors

The most common objectionable behaviors in captive psittacines will likely stem from exaggeration or expansion of normal behaviors. This must be understood in order to have reasonable expectations of reducing, not necessarily eliminating, these behaviors. For example, some degree of vocalization is an innate behavior in psittacines in the morning and late afternoon. Preening is also a normal behavior, occupying a large percentage of time in any situation (wild or captive birds). The critical function of feather maintenance in psittacines, and therefore the need and ability to preen, must be considered when mechanical barriers to feather destructive behavior are considered.

Positive Reinforcement for the Owner

Owners of psittacines often have lives, jobs, and families in addition to their pet bird. This can make compliance with frequent or complex training sessions difficult if not impossible. Besides the need to tailor any recommendations for interactions with the bird to a reasonable schedule, the veterinarian should consider motivation and long-term commitment. Some people cannot or will not consistently devote time to their birds. Others will, if the potential for improvement and the inherent value (e.g., bonding, enrichment, safety) of such interactions is adequately explained. This commitment can be greatly enhanced if both the owner and the bird derive enjoyment from the process. Discovering tricks, treats, and interactions that the bird enjoys is crucial to successful behavior modification. Similarly, the most devoted owners are often created when their bird learns some behavior that is rewarding to the owner (e.g., wave goodbye, play eagle, sing part of “Dixie”). The mutual excitement between bird and owner that this engenders greatly increases the likelihood that that owner will continue to work with the bird. The reinforcement received by the bird also increases the odds of continued performance of these behaviors as well as the acquisition of new ones.

Identifying and Creating the Proper Human-Psittacine Relationship

In nature, most parrots practice “perennial monogamy” or long-term, year-round pair-bonding to the same individual.45 Pair-bonded Glossy Black Cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus lathami), for example, are found to be higher on the dominance hierarchy than any given individual and also to be very closely ranked in the dominance scheme relative to their mates. Much has been written regarding the reasons for the endurance of the pair bond throughout the nonbreeding season. Continued care of juvenile offspring and ease of mate location during subsequent breeding seasons are involved in some species. However, studies of wild cockatoos, lorikeets, and White-fronted Amazons (Amazona albifrons) have shown that the primary advantage seems to be the dominance conferred by a mated pair acting in unison—usually to supplant other conspecifics from a preferred food tree, therefore ensuring optimal nutrition throughout the year.

In captivity the mated-pair relationship may induce behaviors such as territoriality, mate or nest protection, aggression, and ovulation or egg laying when a bird perceives its owner as its mate (Figure 2-5). However, if this perceived relationship can be maintained as a prolonged nonbreeding season alliance, some or most of the negative aspects may be avoided. This is what most veterinarians and behaviorists, intentionally or not, are recommending when they advise clients on frequency and type of interaction allowed with the pet bird, the caveat being to avoid all behavior that can be construed as sexual (petting, feeding by mouth).

Husbandry Considerations

Caging

Many factors are involved in the selection of appropriate caging for pet psittacines.

Bathing

Bathing is critical for both physical and mental well-being. Species and individual variations may dictate in which form this is provided. Many birds enjoy being in the shower with their owners. Many birds also enjoy natural rainfall while in their cage placed outdoors. Before the rain, the perception of a barometric pressure change often sends these birds, particularly South American species, into postural displays in anticipation of the rain. Allowing the bird to dry outside or on a lanai when the weather is suitable encourages normal preening. Some people use blow dryers on their birds. This is potentially drying to the skin and may remove some of the natural grooming instincts. However, it is desirable if no other way exists to assure that the bird stays warm while it dries naturally.

Photoperiod

Generally, increasing day length is a sign of incipient spring and summer, with the concurrent food availability and warm ambient temperature conducive to breeding and raising young. Although many other factors will affect reproduction, the maintenance of a 12-hour light and 12-hour darkness routine will prevent some birds from becoming sexually active.19

Grooming: Nail, Beak, and Wing Trimming

Disease Considerations

Neurologic Disease

Sudden Blindness

In one author’s experience, sudden blindness is most commonly attributable to cataracts or retinal detachment (Figure 2-6). Intracranial tumors, primarily pituitary, are the second most frequent cause. Additional causes include toxicity or severe metabolic disease, but in these cases clinical illness is usually obvious to the owner and the veterinary practitioner. When sudden blindness occurs in the absence of other functional disease conditions, birds may exhibit a variety of reactions. Some become lethargic and unreactive to stimuli. Others become hyperesthetic, which may be interpreted by the owner as either aggression or seizure activity. Although gradual onset of cataracts and acclimation is more common in birds, the practitioner should be aware of the potential for sudden blindness and its presentations.

Heavy Metal Toxicity

The incidence of lead poisoning in birds (and other species) was significantly higher several decades ago than it is today. Variable numbers of birds with lead toxicity were noted to have pronounced neurologic signs (other than the moderate to severe depression normally accompanying any heavy metal toxicity). Hyperexcitability, seizures, and functional blindness have been noted with lead poisoning.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree