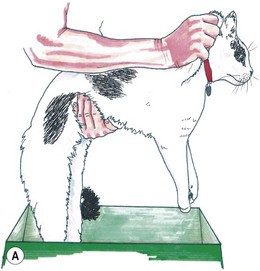

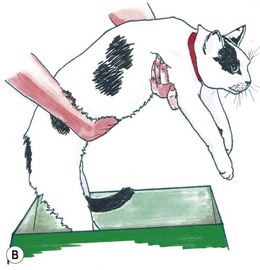

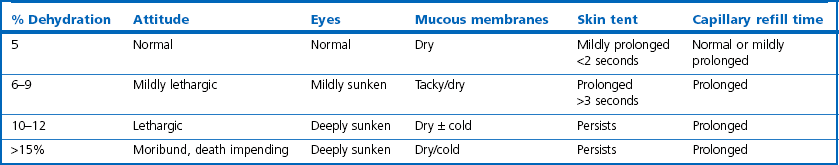

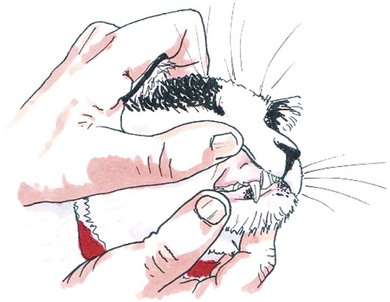

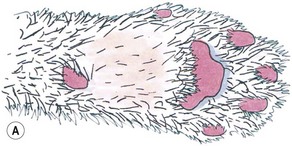

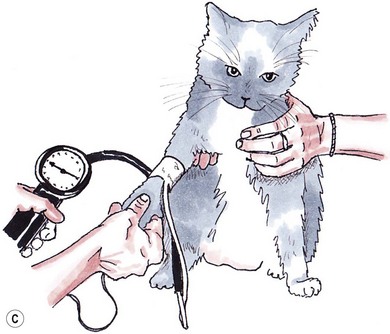

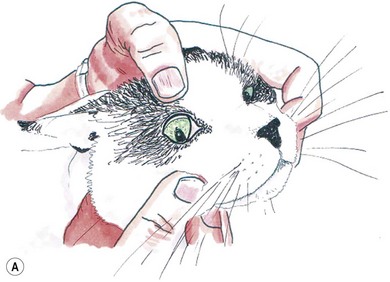

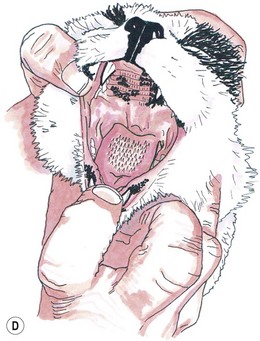

Chapter 1 Regardless of the surgical procedure planned, the clinician should familiarize themselves fully with the medical history. The history can be considered in two parts; the general history and the specific history. The general history involves collection of background epidemiological information for the patient (Box 1-1). Signalment should be confirmed. Owners may, unwittingly, provide inaccurate information on their cat’s age, breed or sex. It should be ascertained whether the cat was acquired as a kitten or as an adult of unknown background. A reasonable estimate of age can be made in cats that are still growing (up to 18–24 months) and in geriatric cats if there is iris discoloration or age-associated disease, e.g., most cats with hyperthyroidism are over 10 years old. Information regarding the cats’ living circumstances is important. Owners of cats living in apartments can usually provide detailed information on toileting, appetite and activity levels that owners of cats that roam will be unable to provide. Owners should be questioned about current medications with the drug, dose, frequency and time of last dosing being recorded. In presurgical patients, special attention should be given to medications that may affect coagulation (e.g., heparins, warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel) and wound healing (e.g., prednisolone). The specific history relates to the presenting complaint (Box 1-2). This establishes what abnormalities the owner has noticed, their duration and the pattern of disease. It is the responsibility of the clinician to find a way of communicating with each owner that best facilitates information flow. Although the problem might not be exactly what the owner perceives it to be, if a problem is reported, there almost certainly is one. A complete preoperative physical examination is essential to identify factors that may affect surgical outcome. Most cats will allow a thorough examination and respond best to minimal restraint. Special care should be taken with cats that are particularly timid or aggressive. Maintaining a quiet environment and avoiding sudden movement is helpful. Doors and windows should be closed. Further information on providing an appropriate environment for examining cats and the most cat friendly consulting room is provided in Chapter 9. The demeanor of the cat and its resting respiratory rate and effort should be observed while it is in its carrier. If the cat appears relaxed, it should be stroked and talked to before lifting it onto the floor or table. If the cat appears aggressive (e.g., ears back and flattened) it is prudent to remove the cat from the top of its carrier swiftly by scruffing the back of the neck with one hand and supporting the cat’s body under its chest with the other hand (Fig. 1-1). Some cats feel threatened when approached to be removed from their cage. Hesitating to remove these cats can precipitate aggressive swiping or biting. A non-aggressive cat can be removed from its carry cage at the start of the consultation and given time to acclimatize while the history is taken. The cat can sit on the consulting table while being gently held or stroked by the owner, or if the cat is not injured or dyspneic, it can explore the room. This can reduce anxiety in an unfamiliar environment before the physical examination begins and permits observation of the cat’s mentation and gait. The ‘window of opportunity’ for examination of the cat can be small and the examination should proceed from least invasive to most invasive procedures, with abdominal palpation, rectal temperature and manipulation of an area suspected to be painful generally performed last. Measurement of systolic blood pressure (SBP) is indicated in any cat with evidence of target organ damage, including cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD), retinopathy or choriodopathy, intracranial signs, cardiovascular signs (murmur, gallop, arrhythmia) or epistaxis. SBP pressure should also be measured in obese cats and where thyroid or adrenal disease is suspected. Given that CKD and hyperthyroidism are the most common causes of hypertension in cats, it is prudent to measure blood pressure routinely in any cat that is 10 years of age or older.1 Measurement of SBP should be carried out at the beginning of the physical examination, after acclimatization. This avoids artefactual, anxiety-induced increases or decreases in blood pressure, known as the ‘white-coat’ effect (Fig. 1-2, Box 1-3). Doppler techniques are preferred over oscillometric techniques for measurement of SBP in conscious cats as they are more accurate and faster to measure.2,3 Figure 1-2 (A) An alcohol swab is used to wet the hair on the palmar aspect of the forelimb adjacent to the metacarpal pad before placement of the Doppler ultrasound probe. Clipping of the hair is not necessary and could contribute to “white-coat” hypertension. (B) Equipment for indirect blood pressure measurement in the cat: ultrasonic Doppler flow detector, sphygmomanometer, blood pressure cuff and coupling gel. (C) Technique for blood pressure measurement with cat gently restrained. The cuff is placed mid-way between the carpus and elbow. The Doppler probe is held lightly over the median artery on the palmar aspect of the forelimb adjacent to the metacarpal pad. (D) Indirect ophthalmoscopy using a Finnoff transilluminator and a 20–30 diopter lens. The examination can usually be completed in low ambient light without topical mydriatics. Otherwise, 1% tropicamide can be used. ([B] With thanks to Henleys Medical Supplies Ltd.). The physical examination can be completed by starting at the head and working caudally. The cat should first be weighed using accurate scales and its body condition score assessed using established 5-point or 9-point scoring systems (see Chapter 6): Check pupil shape and symmetry Examine for discharge or blepharospasm Retract upper and lower eyelids to examine conjunctiva and sclera (Fig. 1-3) Examine cornea, iris and anterior chamber Prolapse nictitating membrane by placing thumb over upper eyelid and retropulsing globe with lower lid retracted (Fig. 1-4). Figure 1-4 Examination of the nictitating membrane. (A) The lower lid is retracted downwards while (B) placing gentle pressure on the globe. Fundic examination is essential when there is suspicion for chorioretinal disease (e.g., toxoplasmosis, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP)) or whenever blood pressure is measured (Fig. 1-2D) Inspect and smell external ear canal for evidence of infection Otoscopic examination to the level of the tympanic membranes, if permitted by the cat. Sedation or anesthesia is required for complete visualization if the cat has sensitive or painful ears Elevate upper lip to assess mucous membrane color, moistness, capillary refill time (CRT) (Fig. 1-5). In comparison to the dog, the normal mucous membrane color for cats is paler. Assess the cat’s hydration status (Table 1-1). Signs of dehydration include dry or tacky mucous membranes, a loss of skin turgor (skin tenting between the shoulder blades), prolonged CRT and enophthalmos. Skin tenting as a measure of hydration can be unreliable in geriatric or emaciated cats and the moistness of mucous membranes is more difficult to assess in cats than in dogs The mouth should be opened (Fig. 1-6). The fauces, tongue and soft palate can be inspected. Subtle jaundice can sometimes be detected first on the soft palate Figure 1-6 Examination of the oral cavity. (A) The cat is reassured and the head is grasped firmly. (B) The neck is fully extended so that the nose points directly upwards. The index finger is placed on the lower incisors to open the jaw. (C) The tongue is raised by pushing the thumb up between the mandibles. (D) Good visualization of the tongue, hard and soft palate and sublingual area is achieved. The underside of the tongue is examined for masses or string foreign bodies by pressing the thumb of the second hand into the intermandibular space to elevate the tongue Assess nasal planum for altered pigmentation, ulceration or crusts Assess nares for symmetry, flare (with increased inspiratory effort), discharge and patency (microscope slide fogs on exhalation) Thyroid gland, larynx trachea, jugular vein With the head fully extended the thyroid lobes can be palpated by sliding the thumb and forefinger in a continuous movement from the larynx to the thoracic inlet. Enlarged thyroid lobes are palpated as a flick through the fingers (Fig. 1-7) The larynx can be gently palpated to elicit a swallow allowing non-invasive assessment of the gag reflex. One or two soft coughs may be elicited While the head is elevated the jugular vein is inspected for distension and/or pulsation. The hair may be damped down if the vein is not visible Mandibular lymph nodes are located rostral and lateral to the mandibular salivary gland. They are palpated by grasping the soft tissues ventral to the vertical ramus of the mandibles and sifting through tissues until the node is felt as a small ‘bean’ that is harder and smoother than the lobulated salivary gland Superficial cervical (prescapular) lymph nodes lie medial to the point of the shoulder, near the clavicle remnant The popliteal lymph nodes lie between the gastrocnemius muscle bellies in the pelvic limbs and must be differentiated from surrounding fatty tissue The axillary, inguinal lymph nodes and often prescapular lymph nodes, are not palpable unless enlarged Palpate the cardiac apex beat noting intensity and presence of any thrills Place the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the sternum with the cat standing or sitting and auscultate the heart in sternal and parasternal locations. In a veterinary hospital environment the normal feline heart rate ranges from 140 to 200 beats per minute Take the heart rate and palpate the femoral pulses simultaneously, noting the pulse amplitude, pulse symmetry and any pulse deficits. Evaluation of femoral pulses is more difficult in the cat than the dog as they are more easily occluded during firm palpation, but their presence should be ascertained Listen for murmurs, grade them from I to VI and find the point of maximum intensity (PMI). Murmurs can be induced if the stethoscope is pressed too firmly against the chest Listen for gallop (extra, abnormal) heart sounds. S4 is the gallop sound most often heard in cats. It arises from atrial contraction against a diastolically compromised ventricle, e.g., in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The S3 gallop is rare in cats. It is caused by sudden cessation of rapid ventricular filling with vibration of the walls and muscles Assess the rhythm of the heart as regular, regular–irregular (e.g., sinus arrhythmia, rare in cats compared with dogs) or irregular–irregular (e.g., atrial fibrillation)

Preoperative assessment for surgery

Arrival and history taking

History taking

Physical examination

Handling and acclimatization

Blood pressure measurement

Head-to-tail examination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree