CHAPTER 121 Pregnancy Diagnosis in Llamas and Alpacas

Diagnosis of pregnancy in llamas and alpacas can be performed by indirect or direct means. The aim of indirect methods is to distinguish between the follicular versus luteal phase of the ovarian cycle, and usually involves assessment of sexual receptivity using a “teaser” male, or measurement of progesterone concentration in blood or milk. Direct methods involve palpation, ballottement, and ultrasonography of the conceptus and associated fluid. Tactful use of indirect and direct methods of assessing pregnancy status will provide the clinician a broad array of breeding management schemes that may be adapted to suit the needs of the individual producer.

THE EARLY EMBRYO

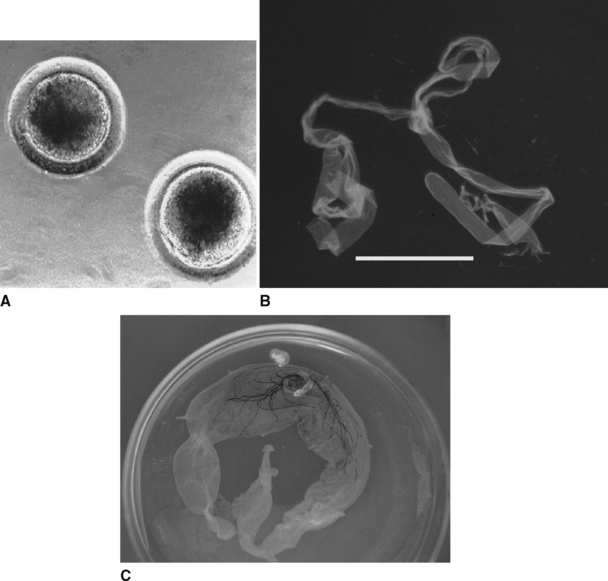

The early embryo resembles that of other ruminant species (Fig. 121-1), but cells of the morula have a darker cytoplasm, and hatching from the zona pellucida usually occurs before the embryo reaches the uterus. Though initially spherical (at ≤7 days after mating), the hatched blastocyst quickly elongates into a delicate filamentous embryonic vesicle that occupies most of one uterine horn by 10 days after mating (Fig. 121-1). Camelids have a diffuse chorioepithelial type of placenta. The chorionic membrane has unbranched villi that form an intricate interdigitation with corresponding undulations in the endometrial epithelium.

SEXUAL BEHAVIOR AND SYSTEMIC PROGESTERONE

It is convenient to consider sexual behavior in parallel with systemic concentrations of progesterone as indicators of pregnancy status in llamas and alpacas because a causal relationship exists between the two. By inference from the results of a number of studies in llamas and alpacas,1–6 systemic concentrations of progesterone are inversely related to sexual receptivity. That is, females under the prevailing influence of progesterone are nonreceptive to sexual advances of a male.

In an often-cited study of the sexual behavior of alpacas,6 it was stated that estrus may last for 21 to 36 days with occasional short periods (≤48 hours) of nonreceptivity. In a more critical study in llamas,3 however, periods of constant estrus of at least 30 days were observed (end of observational period), but extended to at least 90 days in some individuals. No mention was made of short periods of nonreceptivity, other than a prolonged period of diestrus. In nonmated females, follicular waves emerge at regular periodic intervals without interruption by ovulation or luteal gland development.7 Circulating concentrations of estrogen wax and wane in correspondence with growth of the dominant follicle of each wave;8 however, no obvious relationship between estrogen concentration and sexual receptivity has yet been detected.8 The relationship between follicular growth, estrogen concentration, and sexual receptivity has not been quantitatively evaluated and warrants further research, but it is clear that in the absence of progesterone, female llamas and alpacas are more or less receptive continuously.

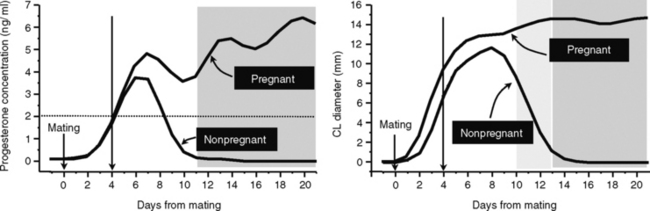

Based on the assumption that sexual nonreceptivity is a reflection of elevated systemic progesterone concentration, the strategy for testing receptivity is similar to that for testing systemic progesterone concentration as an indicator of pregnancy status (Fig. 121-2). Ovulation occurs very consistently 1 to 2 days (mean, 30 hours) after the first mating (see Chapter 118), but plasma progesterone does not rise significantly until 4 days after mating.2 Plasma progesterone concentration peaks 7 days after first mating and decreases rapidly thereafter in nonpregnant animals to a nadir at 11 days after first mating. During the first 3 to 4 days after mating, when the corpus luteum (CL) is forming and progesterone concentrations are low, some females remain receptive to the male. In pregnant animals, plasma progesterone concentration will remain elevated until the last 2 weeks of gestation, at which time it begins to decline to a nadir 24 hours before parturition.9 In one study, plasma progesterone did not exceed 0.4 ng/ml in nonmated nonovulatory llamas, but it remained in excess of 2 ng/ml in all pregnant llamas after day 11 after mating.2 In the same study, CL diameter assessed by transrectal ultrasonography was highly correlated with plasma progesterone concentration (r = 83%; P < 0.0001) with the caveat that progesterone decreased 1 to 3 days before CL diameter decreased, at the time of luteolysis (see Fig. 122-2). Interestingly, a decrease in mean plasma progesterone concentration was detected between 9 and 11 days after mating in pregnant llamas, as well as subtle decrease in luteal diameter.2 The transient drop in progesterone was coincident with the initiation of uterine-induced luteal regression in nonpregnant animals and it was suggested that the rescue and resurgence of the corpus luteum between 9 and 1 days after mating represents luteal response to pregnancy (or maternal recognition of pregnancy).2 Measurement of progesterone concentration in the milk of pregnant and nonpregnant llamas and alpacas during the first 14 days after mating also revealed a parallel relationship with the concentration of progesterone in the blood.10

Based on these observations, a diagnosis of ovulation may be made between 4 and 8 days after mating by (1) behavior assessment, (2) measurement of progesterone concentration in blood or milk, or (3) measurement of CL diameter. A diagnosis of nonpregnancy may be made by day 11 after mating by detecting behavioral receptivity or basal progesterone concentrations and a regressing CL (see Fig. 121-1).

Test of sexual receptivity is an indirect test of the presence of progesterone, and measurement of systemic progesterone is a measurement of luteal function—neither are direct indicators of pregnancy. Hence, behavior assessment and progesterone testing may be more appropriately referred to as methods of diagnosing nonpregnancy because luteal gland function may be elicited by factors other than pregnancy. Spontaneous ovulation has been reported in approximately 10% of females not exposed to a male5,7,11 and may result in a false positive diagnosis of pregnancy. Pathologic processes such as luteal cysts,4,12 embryo/fetal loss,1 and abnormalities of the tubular genitalia may result in a prolonged luteal phase and a false positive diagnosis of pregnancy. In one llama that was ultrasonically monitored daily after embryonic loss, luteal regression had not occurred by the end of the observational period (70 days; G.P. Adams, unpublished). Based on repeated ultrasonographic examinations and final inspection at the time of ovariohysterectomy, a clinical diagnosis of a persistent corpus luteum was made in one llama with closed pyometra (cervical adhesions) and in another llama with congenital segmental aplasia and mucometra (G.P. Adams, unpublished). In both instances, the animals were assumed to be pregnant based on behavior and repeated measurement of plasma progesterone during the preceding months. Plasma progesterone concentrations remained above 2 ng/ml, and were unusually high (8 ng/ml) in some samples. The pathogenesis of these irregularities has not been explored and the predictive value of subnormal or supranormal levels of progesterone is unknown. Depending on the range of normal values established by the respective laboratory, progesterone values between 1 and 2 ng/ml are equivocal and warrant repeated measurement.

In a study of the accuracy of behavior testing as an indicator of pregnancy status,13 the proportion of correct diagnoses ranged between 84% and 95% in llamas and alpacas at 70 to 125 days of gestation. Although convenient and useful, assessment of sexual behavior is confounded by its subjectivity. Submissive behavior in llamas and alpacas is similar to receptive behavior; aggressive behavior in a male or timid behavior in a female may result in submission to mating and mask nonreceptive behavior. Conversely, an inexperienced male may be easily intimidated by a dominant female, and occasionally, inexperienced females refuse to adopt a prone position and need to be restrained for mating. Although behavior and progesterone testing can be extremely useful management tools, they must be used strategically and only for presumptive diagnosis of pregnancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree