The positive psychosocial effects of human/animal relationships engage our interest, arising from our own firsthand experiences with pet animals and our scientific curiosity, as well as the practical questions concerning how best to include pets as an adjunct for treatment for an autistic child or a paraplegic veteran, or to enhance the quality of life of an elderly person in an assisted-living facility. Despite the ever-growing research literature on the psychosocial effects of animals, a significant gap remains between that knowledge base and implementing it into treatment or support services for psychosocially vulnerable people. This chapter first reviews the research-based information about the benefits of pets, especially for the most vulnerable people, and then addresses the practical implementation of this expanding research.

5.1.1 Background and definitions

Typically, animal-assisted interventions (AAI), including animal-assisted activities (AAA), medically directed animal-assisted therapy (AAT), and uses of animals in animal-assisted education (AAE) are arranged in settings where the contact with the animal and the handler is scheduled for residents in a facility. These settings generally do not take into account the specific needs or interests of the person being assisted. Full-time exposure to animals is not usually provided, and the handler differs from the person being served the intervention.

This chapter suggests that to enjoy the positive effects, a relationship with an animal should be individually tailored to the psychosocial characteristics of the person. For example, full-time contact sometimes offers greater potential than a part-time relationship to impact the person’s life. Therapeutic psychological relationships with animals arise with assistance animals, working animals, and companion animals, where a special handler of the animal may or may not be involved. Early uses of assistance dogs emphasized them helping in specific utilitarian tasks, such as aiding those with visual, hearing, or ambulatory disabilities, but by now their provision of psychologically therapeutic benefits, contact comfort, or as a social lubricant, also is highly valued (Hart, 2003). Dogs now fulfill a growing number of therapeutic roles, perhaps most notably including assisting people with mental illness.

The breeding and methods for training assistance dogs also are more varied than in the past. While no standardized certification criteria have been legislated or regulated in the USA pertaining to assistance animals, leaders in the various types of equine therapy have developed their own certification programs. In the USA, providers associated with therapeutic horseback riding programs generally affiliate with the North American Riding for the Handicapped Association (NARHA, 2010), a centralized professional organization which offers three levels of certification for instructors. In addition, specialty certification is available for instructors on carriage driving and gymnastics on a horse, termed vaulting. As a reflection of the fact that horses make a growing contribution to the mentally ill, a subsidiary section of NARHA focuses on mental health and is called the Equine Facilitated Mental Health Association (EFMHA, 2010).

5.1.2 Can pets be prescribed?

The positive results that have been reported for health effects of pets have spurred some mental health practitioners, aware of the tendency to “prescribe pets,” to formulate standardized techniques for offering contact with companion animals for people with disabilities or special needs. The role of pets is often assessed among individuals who have chosen to keep pets, such as populations of vulnerable individuals with disabilities, autism, Alzheimer’s disease, AIDS, or the elderly. However, profiling pets as though their effects for people of such groups are uniform has proven to be not useful when attempting to assess and predict which individuals would be likely to benefit from periodic or sustained contact with companion animals. Community-based epidemiological studies of pet keeping produce useful results for analyzing the geographic context and demographic factors that may be significant. To be able to effectively “prescribe” pets, we will need to become knowledgeable about those cases where pets are not associated with health benefits or may even add to the burden of vulnerable individuals or be harmful, as well as the cases where the animals are associated with positive effects.

5.1.3 Subcultures and psychosocial effects of pets

Epidemiological studies of entire communities identify subcultures where certain individual circumstances, neighborhoods, geographical features, or special situations are associated with beneficial or adverse health parameters. One classic epidemiological study by Ory and Goldberg (1984) revealed that pets were associated with negative indicators for elderly women living in rural settings, but with positive indicators for women in suburban and urban settings, suggesting a varying role of the pet with geographic location. The combination of higher socioeconomic status and pet ownership was associated with more positive indicators of happiness for women (Ory and Goldberg, 1983); however, pet ownership was more typical among less affluent women. Weak attachment to a pet was associated with not being in a confidant relationship with the spouse and was also associated with unhappiness, when compared with non-owners and attached owners whose spouses more often were confidants.

A fairly recent community-based, longitudinal study examined over a one-year period whether attachment to companion animals was associated with changes in health among older people (Raina et al., 1999). Non-owners showed greater deterioration in their activities of daily living than pet owners, but the pet owners as a group were younger, more likely to be married or living with someone, and more physically active. Pet ownership was a positive factor associated with the change in psychological well-being of participants over the one-year period.

5.1.4 The type of pet matters

Selection of the type of pet is important in the outcome. For example, people who are burdened in their personal circumstances or health status, as is common for the elderly, can benefit from pets despite the pet’s care required, especially if they select a low-care cat rather than a dog or horse. Benefits were associated with cat companionship for men with AIDS (Castelli et al., 2001) and middle-aged women giving care to family members with Alzheimer’s disease (Fritz et al., 1996); in contrast, having a dog was more problematic in these two studies.

The term pet covers a wide range of animals and relationships, as families seek out pets to fill different roles. The pet’s treatment depends on the family’s context, traditions, and expectations. A study of residents in Salt Lake County revealed that pet-keeping practices vary with neighborhood and community (Zasloff and Hart, unpublished results). Zip code areas predicted the sources residents used in acquiring their pets with some showing high levels of pet adoptions from shelters. Other neighborhoods favored purebred animals; still other areas were associated with high adoptions of feral cats.

Employing epidemiological methods with statistical representation of the entire community offers a view of the context, including the community’s affluence, geography, age, gender, and ethnicity of pet-owning participants. By examining microneighborhoods and subcultures, we can more accurately profile the range of styles of pet ownership characteristic in our diverse societies, as well as identifying additional questions that need to be clarified.

5.1.5 Focus on the elderly

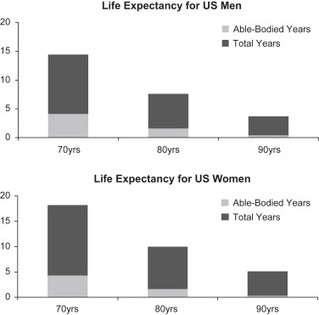

Considering age, the elderly are a growing population where animals can play a special supportive role. However, as mentioned above, the animal must be highly individualized to match the person with respect to personal history, living situation, and general health. As people age, they can be swamped in losses. Their former social networks shrink as they leave the workplace, move into smaller homes, lose friends and family members who have moved away or died, and/or experience chronic health problems or disabilities. The Activities of Daily Living that are used in assessing a person’s active-life status are portrayed in Table 5.1, showing basic activities, as well as instrumental ones required for fully independent living. To put this into clear perspective, Figure 5.1 shows the years of life expectancy for men and women at ages 70, 80, and 90 years; also indicated is the able-bodied portion of their life expectancy, revealing that most people experience a substantial period of disability at the end of their lives when they are unable to perform all the activities of daily living without assistance, representing further losses (Crimmins et al., 1996). Further, the person’s cohort shrinks over time as the like-aged counterparts die at a growing rate. Among a person’s counterparts in the USA, 76% remain alive at 70 years of age, 53% at 80 years, 21% at 90 years, and 2% at 100 years. Having a companion animal can offer a source of reliable and accessible companionship. In one study of elderly dog owners, a majority said their dog was their only friend and believed their relationship with their dog was as strong as with humans (Peretti, 1990).

Figure 5.1 Although the number of years of life expectancy for women at 70, 80, and 90 years of age exceeds that of men, the expected period of disability is also greater for women than men and from the age of 70 is a majority of the remaining years of life, for both men and women (from Crimmins et al., 1996). Being unable to perform essential tasks in the Activities of Daily Living was defined as a disability.

Table 5.1 Activities of Daily Living: lists of activities that are commonly used by medical professionals, usually with the elderly, to assess their fundamental functioning (left side) and ability to live independently (right side).

| Activities of Daily Living: Basic | Activities of Daily Living: Instrumental |

Personal hygiene Dressing and undressing Eating Transferring from bed to chair, and back Voluntarily controlling urinary and fecal discharge Elimination Moving around (as opposed to being bedridden) | Doing light housework Preparing meals Taking medications Shopping for groceries or clothes Using the telephone Managing money Using technology |

Understanding how best to optimize contact with animals for elderly people to increase benefit for them but not create a burden in their varied circumstances is an urgent question for society today, and one that is touched on several times in this chapter. Bridging the gap between the research results and the practitioners’ needs for specific and practical information requires evidence-based tailoring of the animal contact for effective therapeutic assistance with patients.

5.2 Goals of this chapter

This chapter is intended to present some highlights from the research literature, while also addressing the gap between research and practice and pointing the way toward an integrated translation of knowledge into helpful programs and practice. It also points to the importance of considering the specific roles of different animal species, dogs, cats, and horses, birds and fish, in enhancing the quality of human lives. Some related recent reviews of relevance to this theme are those by Wells (2007, 2009) on the health effects of dogs, and the intriguing roles of companion animals in detecting medical conditions, such as the presence of emerging cancer or predicting an impending seizure attack. Another paper, by Barker and Wolen (2008), reviews over 100 studies on the health benefits of human/animal interactions.

5.3 The potential of pets to enhance the quality of life

An important point to emphasize is that while companion animals offer potential enhancements to a person’s quality of life that can stem an unraveling decline into disability or disease, they only rarely offer a pathway to curing disease. As an unconditional support system, pets can be recruited for contact at any time of day or night. Essential comfort, relaxation, and entertainment are near at hand. The conflicts with the non-verbal animal are few as long as the person avoids behavior problems through careful pet selection and management.

Human relationships, or a lack of them, can promote health, or produce stress. Increased mortality rates are associated with decreased social connections (Berkman and Breslow, 1983). Despite family, friends, and other support services, at times of challenge and heartbreak, some vulnerable people will be without the social relationships they need for a reasonable quality of life. Persons who are facing hearing, visual, or mobility disabilities, living alone in later years, or experiencing the onset of serious medical problems, may be at particular risk. Even temporary crises can be paralyzing in their impact.

Anyone who is socially isolated, and possibly experiencing an increase in medical problems, may begin to feel profoundly alone. The high costs of loneliness and a lack of social support to human health are well documented (House et al., 1988). While the link of loneliness and depression with cancer and cardiovascular disease has long been recognized (Lynch, 1977), depression is now considered to be a central etiologic factor of these diseases (Chrousos and Gold, 1992).

Recognizing that some elderly individuals are seriously challenged with their health problems and inability to perform activities of daily living, one community program over two decades ago placed animals, usually dogs, with elderly and provided some support for their care (Lago et al., 1989). Cats require less effort than dogs, and may be more appropriate companions for some elderly persons. While the effects of cat ownership are not well studied in this context, an Australian study found better scores on psychological health among cat owners than non-owners (Straede and Gates, 1993). Cat-owning women rate their cats highly in providing affection and unconditional love (Zasloff and Kidd, 1994a). A study by Karsh and Turner (1988) found that long-term cat owners were less lonely, anxious, and depressed than non-owners; the study even found that the pet owners reported improvements in blood pressure.

Permanent institutional living almost always curtails the person’s quality of life, and reduces contact with the world at large, along with increasing the cost of living. And it is widely recognized that for some people in residential retirement communities, companion animals can contribute to their psychosocial health, and help extend by months, or even a few years, the period of living independently.

But what about precarious persons or the elderly who still live at home? Animal-assisted activities (AAA) or therapy (AAT), and other types of support related to pets, generally are not offered to precarious individuals who still live at home. An obvious gap exists in finding approaches to filling this need and testing the various approaches.

Finally, in introducing this section, it should be emphasized that a well-documented area is for children with mental or neuromuscular disabilities that benefit greatly from the extraordinary experience of therapeutic horseback riding, an occasion that affords joyous human social support as well as the unique sensation and physical challenge of riding the horse (Hart, 1992). Even the families of the afflicted child seem to benefit.

In short, a wide array of animals, and different contexts, give rise to a variety of psychosocial effects. These are organized as four main categories and reviewed in the section below.

5.3.1 Effects on loneliness and depression

Most people that are caregivers of pets value companionship most in their relationships with pets. However, for those who are isolated, the lack of companionship, depression, and lack of social support are major risk factors that can impede a person’s well-being and even increase the likelihood of suicide or other maladaptive behaviors. Individuals experiencing adversity are more vulnerable and subject to feelings of loneliness and depression.

The concept of social support creating both main and buffering effects against stress is well known in discussions of human social support (Thoits, 1982), and pets seem to, at times, substitute for human companions in fulfilling this role. A study by Siegel (1993) showed that animals offer their elderly human companions a buffer of protection against adversity, as manifest in fewer medical visits during a one-year period.

In a notable review paper, psychological, social, behavioral, and physical types of well-being, pertaining to benefits of pets, were examined with regard to social support (Garrity and Stallones, 1998). Pet association frequently appeared beneficial, both directly and as a buffering factor during stressful life circumstances, but did not occur for everyone.

Descriptive, correlational, experimental, and epidemiological research designs have been used to assess the effects of contact with companion animals on human well-being. Correlational studies, whether of a cross-sectional or longitudinal type, often assess just whether or not a pet is present and have not taken into account the wide differences in individual variation of the target population, type of pet, and environment. These issues will be addressed in this section.

Elderly people

Among elderly people in one study who were grieving the loss of their spouses within the previous year and who lacked close friends, a high proportion of individuals without pets described themselves as depressed; low levels of depression were reported by those with pets (Garrity et al., 1989).

One of the unexplored confounding aspects in the analysis of the potential beneficial effects of pets for the elderly is that people who seek out animal companionship may be more skilled in making choices that maintain their own well-being than non-pet owners. The traits of dependability, intellectual involvement, and self-confidence are strong characteristics that are established at a young age and continue throughout life; individuals who as young people express this planful competence seem able to take adverse life events in their stride and take effective actions to keep their lives on track (Clausen, 1993). A decision to live with an animal could be one aspect of taking effective action in one’s life. Individuals keeping pets may also have acquired social skills and abilities that were reflected in the decision to have a pet.

It is tempting to ascribe the beneficial effects of pets for grieving elderly (Garrity et al., 1989) to the constant responsibility to nurture another individual, the loving devotion of a pet, and even the laughter that a pet inevitably brings into everyday life. Living alone is common in elderly people, and this lifestyle itself may be inherently stressful. Loneliness is associated with various diseases. Elderly women living alone were found in one study to be in better psychological health if they resided with an animal: less lonely, more optimistic, more interested in planning for the future, and less agitated than those women who lived without a pet (Goldmeier, 1986). In contrast, women living with other relatives did not show an extra boost with a pet. Women graduate students who lived alone also showed a protective effect of a pet: those living with a companion animal, a person, or both, rated themselves as less lonely than those living entirely alone (Zasloff and Kidd, 1994b).

However convincing the above findings are, the psychosocial benefits, such as lowered risk of depression, are not necessarily accompanied by general differences in health status. No differences in health status were found among a large group of people (21 to 64 years of age) with and without pets (Stallones et al., 1990). The same finding was reported in a large study on just the elderly (Garrity et al., 1989).

People with mental illnesses

In the area of disabilities, we have traditionally thought of service dogs as being employed in the service of the blind, deaf, or hearing-impaired, and those who must rely on the use of wheelchairs. A new development is the contribution of service dogs for the mentally impaired or disabled. For this new area employing psychiatric service dogs, the formalized tasks of the dog include providing companionship, contact comfort, and affection, all of which contribute to the stabilization of mental health for someone suffering from mental illness (Psychiatric Service Dogs Society, 2010). For a syndrome very much in the public eye, post-traumatic stress disorder following war experiences, the syndrome is being treated at some centers by the warmth and acceptance dogs offer when providing tactile contact and calming the patient.

The use of psychiatric service dogs is broadening the concept of service dogs. Persons being treated work with dog training specialists and peers in training their own dogs. Clearly, professionals working in this new field recognize that the dog is just one aspect of treatment, along with pharmaceutical treatment and counseling assistance from human health professionals, as well as intervention with veterinarians when indicated.

The use of birds in residential facilities is an interesting sideline of this field. Depressed community-dwelling elderly in one study were less negative psychologically after prolonged exposure to pet birds (Mugford and M’Comisky, 1975). Depressed elderly men at an adult day health care program exposed to an aviary, and who ended up actually using the aviary, had a greater reduction in depression than those that did not interact with the aviary. In fact, the latter group showed no overall difference in depression (Holcomb et al., 1997). Those seeking out the aviary also apparently were more interactive with family and staff members. Along the same lines, lonely elderly people in a skilled rehabilitation unit who were given a budgerigar in a cage for a period of 10 days showed decreased depression (Jessen et al., 1996).

People who are mentally ill have also been a recent focus of the therapeutic equine advocates who now have an organization, the Equine Facilitated Mental Health Association (EFMHA, 2010). One difference between dogs and horses is that whereas a dog can be available 24 hours a day to provide companionship and comfort, equine-assisted therapy requires a significant infrastructure and human organization in order to provide treatments, even once a week. The equine therapists point out, however, that the power, beauty, and strength of a horse compel the attention of the rider. For some patients the horse is uniquely effective in motivating the person and facilitating treatment.

Many communities have an equine-facilitated program operating nearby and if not currently utilized some of the horses could be cross-trained perhaps to provide not only the physical rehabilitation, but some mental therapy to a different set of patients. Green Chimneys (2010) is an example of a comprehensive residential treatment center for mentally disturbed children where equine-facilitated therapy is one of the important treatment modalities that are available.

People with a disability or requiring clinical care

The third topic in this section on depression and loneliness concerns benefits of pets for people in long-term treatment facilities, where irreversible disabilities like deafness and diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease are common. While a full-time therapeutic pet might seem best in terms of reducing loneliness, the pet can be just an occasional friend. AAT provided once or three times a week to elderly people in long-term facilities can result in a significant reduction of loneliness (Banks and Banks, 2002).

One important and common disability, loss of hearing, limits communication and predisposes people to feeling isolated and lonely, even when others may be nearby. In these circumstances, a hearing dog can offer ameliorative benefits aside from alerting the caregiver to the phone ringing. A dog, being a full-time companion, ends up being a conversational partner that responds behaviorally to the statements and moods of other people nearby, facilitating the person to socialize within the community. People with impaired hearing and a hearing dog rated themselves as less lonely after receiving their dogs, and also were less lonely than those who were slated to receive a hearing dog soon (Hart et al., 1996).

Alzheimer’s disease is one of the most challenging conditions for both the patient and the caregivers, and one that will increase with the changing demographics and growing aging population in much of the Western world. As noted, a cure is not to be expected from a pet, but some specific and important aspects of quality of life and patient management may be helped with strategic employment of animals. Another study of nursing home residents with dementia found that they had improved orientation to the days of the week based upon the presence or absence of a Canine Companion who participated at a day program on Tuesdays and Fridays (Katsinas, 2000). Dogs were used to join the patient for short walks within the facility; in the case of wandering a bit, the dog could be called back and the patient would also return.

Another study of a closed psychiatric ward for persons with dementia found in recordings of the general ward noise with a sound level meter that the noise levels were substantially decreased in the experimental ward during the dog’s two 3 hour visits each week, but not in the control ward (Walsh et al., 1995). Fewer loud spontaneous vocalizations and aggressive verbal outbursts resulted in a significantly lower intensity of noise levels in the experimental ward during the presence of the dog.

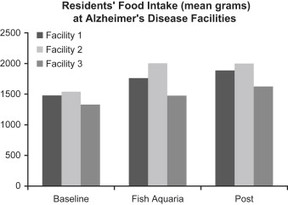

Here again, the pet does not have to be a dog or even a cat. Introducing fish aquaria into three residential facilities for people with Alzheimer’s disease resulted in an increased average nutritional food intake as shown in Figure 5.2, with weight gains for the residents who previously had been losing weight (Edwards and Beck, 2002). Residents remained at the dining table longer and were more attentive in the presence of the aquaria, eating the prepared food and requiring significantly less nutritional supplements such as Ensure (a 25% reduction).

Figure 5.2 A virtually unexplored treatment for patients’ disinterest in food and lack of appetite that is common in Alzheimer’s disease and cancer may be exposure to animals. Elderly residents in facilities for Alzheimer’s patients, when provided a fish aquarium in their dining room, increased their nutritional intake and also had a weight gain (from Edwards and Beck, 2002). The increased intake persisted for some weeks after the aquarium was removed.

These three studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease highlight the opportunities to consider less-conventional benefits of animals contributing to the person’s quality of life, by increasing their engagement in living, such that they eat more nutritiously, are more aware of days of the week, and express less distress in aggressive and loud outbursts. These outcomes—appetite, awareness of time, and aggressive outbursts—involve issues that regularly challenge caregivers and family members who assist in the management of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and some other diseases as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree