Chapter 164 Pleural Effusion

Pleural effusion is an abnormal accumulation of fluid within the pleural space and is a clinical manifestation of conditions such as pyothorax, feline infectious peritonitis, congestive heart failure, intrathoracic neoplasia (e.g., lymphoma, thymoma, pulmonary neoplasia, mesothelioma), chylothorax, heartworm disease, hemothorax, hypoalbuminemia, lung lobe torsion, and diaphragmatic hernia. Pleural effusion is usually suspected from clinical signs and physical findings and is confirmed by thoracentesis or thoracic radiography.

ETIOLOGY

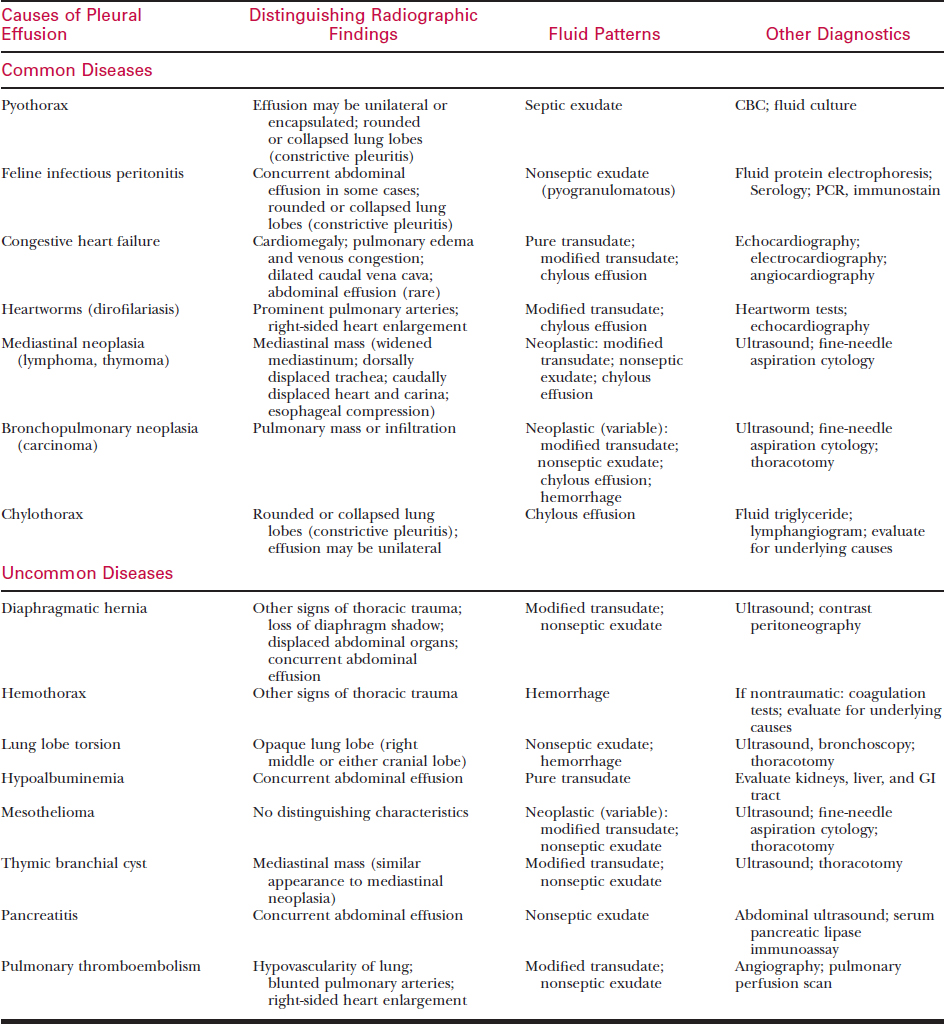

Pleural effusion occurs when one or, more often, a combination of the factors that determine pleural fluid dynamics are altered so as to increase fluid formation, decrease fluid absorption, or both. For example, pleural effusion is often associated with congestive heart failure (CHF) because increased capillary hydrostatic pressure results in increased pleural fluid formation. Extreme hypoalbuminemia may lower systemic colloidal osmotic pressure sufficiently to cause increased formation and decreased absorption of pleural fluid. Inflammation of the pleura may increase the formation of pleural fluid because of increased blood flow (hydrostatic pressure) and permeability of the pleural capillaries along with increased intrapleural colloidal osmotic pressure due to a higher concentration of protein in the fluid. Pleural effusion may also result from lymphatic insufficiency caused by thoracic duct obstruction, intrathoracic neoplasia, pleural thickening, or lymphatic hypertension secondary to CHF. The major causes of pleural effusion in dogs and cats are listed in Table 164-1.

CLINICAL SIGNS

DIAGNOSIS

Suspect pleural effusion on the basis of clinical signs and physical findings. Confirm pleural effusion by thoracentesis (see Chapter 3) or thoracic radiography (see Chapter 159). The cause is often determined through analysis of pleural fluid obtained by thoracentesis, in conjunction with post-thoracentesis radiographs. Depending on the suspected etiology, consider other diagnostic procedures such as laboratory evaluations, cardiac evaluations, ultrasonography, and specialized imaging procedures (contrast radiography, scintigraphy, computed tomography [CT]). Rarely, exploratory thoracotomy is required for definitive diagnosis.

Physical Examination

Thoracic Auscultation and Percussion

Other Physical Findings

Thoracic Radiography

Routine thoracic radiography is generally effective for confirming pleural effusion.

The radiographic signs of pleural effusion include separation of the lung lobes from the parietal pleura and sternum by extrapulmonary fluid density (i.e., compression of lung lobes by a pleural fluid density), fluid-filled interlobar fissures producing a scalloped appearance to the edges of the lungs, and obscuring of the cardiac and diaphragmatic shadows, which is referred to as the silhouette sign (see Chapter 159). There is also widening of the mediastinum and blunting or filling of the costophrenic angles by intrapleural fluid density on a ventrodorsal view. In addition, the various causes of pleural effusion may be associated with other radiographic findings of diagnostic significance (see Table 164-1).

Because many intrathoracic structures are obscured by the presence of pleural effusion, obtain radiographs after the removal of pleural fluid to facilitate visualization of such abnormalities as mediastinal mass, cardiomegaly, intrapulmonary lesions (masses, infiltrates, vascular changes), lung lobe torsion, or diaphragmatic hernia (see Table 164-1).

Thoracentesis and Fluid Analysis

Thoracentesis

Pleural Fluid Analysis

Perform the following analyses on the pleural fluid.

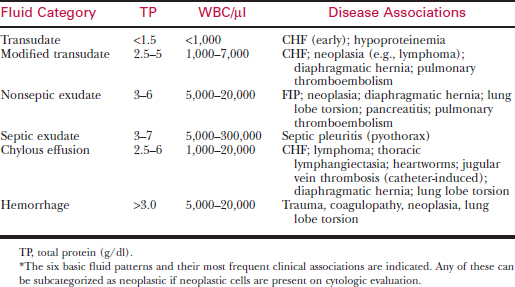

Classification of Pleural Fluid Patterns

On the basis of these analyses, pleural effusions are generally classified into one of several patterns: transudate, modified transudate, nonseptic exudate, septic exudate, chylous effusion, or hemorrhage (Table 164-2). In addition, any of these can be subcategorized as neoplastic versus non-neoplastic depending on whether or not neoplastic cells are present on cytologic evaluation. There can be considerable overlap between these various categories; nevertheless, they are helpful for understanding the pathogenesis and determining the cause of pleural effusions.

Nonseptic Exudate

Chylous Effusion

Chylous effusions are caused by extravasation or leakage of intestinal lymph (chyle) from an obstructed or ruptured thoracic duct. Chylothorax in dogs and cats may be idiopathic or associated with trauma, thoracic lymphangiectasia, intrathoracic neoplasia, heart disease, heartworms, venous thrombosis, diaphragmatic hernia, or lung lobe torsion (see under Chylothorax). The milky white opaque fluid contains mostly lymphocytes accompanied by variable numbers of neutrophils, depending on the duration of the effusion and the extent of the resulting pleuritis (see Table 164-2). Chylous effusions are confirmed by the presence of chylomicrons, which can be demonstrated by the ether clearance test, by the presence of a cream layer on refrigeration, and microscopically by the presence of Sudan-positive orange fat droplets, but these are relatively insensitive methods.

Laboratory Evaluations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree