19 PLASMA CELL NEOPLASIA

1 Which disorders are included in the plasma cell neoplasia group?

Plasma cell neoplasms include multiple myeloma, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, solitary osseous plasmacytomas, and extramedullary plasmacytomas. Multiple myeloma is the most important based on incidence and severity1,2 and has been reported in the dog, cat, horse, cow, and pig.3

Each of these disorders is thought to arise from a single neoplastic B lymphocyte (monoclonal proliferation), although biclonal and polyclonal tumors have been described. Extramedullary plasmacytomas arise outside the bone marrow, and their behavior varies with site of origin. Cutaneous and oral extramedullary plasmacytomas are relatively common in older dogs and generally benign in behavior.4 In contrast, noncutaneous extramedullary plasmacytomas, especially those arising within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, are much more aggressive in behavior and often spread to regional lymph nodes. Solitary osseous plasmacytomas arise as a focal skeletal lesion and frequently progress to systemic multiple myeloma.2

2 How common is multiple myeloma in veterinary species?

In the dog, multiple myeloma is relatively uncommon, accounting for less than 1% of all malignant neoplasms, approximately 8% of all hematopoietic tumors, and 4% of all bone tumors.1,5 Older dogs are typically affected, with a reported age distribution of 8 to 10 years.1,3 No gender or breed predisposition is consistently reported.2

In other domestic species, occurrence of multiple myeloma is very rare. In the cat, multiple myeloma accounts for less than 1% of all hematopoietic tumors.5 As with dogs, older cats are most often affected, and no gender predisposition has been reported.2,5

3 Has an etiology been found to explain the development of multiple myeloma?

No specific etiology has been determined to cause multiple myeloma in domestic species. Genetic predispositions, viral infection, chronic immune stimulation, and carcinogen exposure may all play a role in tumor development.1 In one large case series of canine multiple myeloma, German Shepherds were overrepresented.1,3 Cocker spaniels may be overrepresented in devel-opment of extramedullary plasmacytomas, accounting for 24% of affected dogs in one study.3 Multiple myeloma has not been associated with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection in the cat.1

4 What is the M-component?

The M-component, also called myeloma protein or M protein, refers to the immunoglobulin proteins or protein fragments produced by secretory neoplastic B lymphocytes. It includes the various immunoglobulin types (IgG, IgA, IgM), light chains (Bence Jones proteins), and heavy chains. The production of M-component by neoplastic B lymphocytes is termed paraproteinemia. Although this is a more common manifestation of multiple myeloma, it may also occur rarely in association with other plasma cell neoplasms.2,3,6

IgG and IgA paraproteinemia have an almost equal rate of occurrence in the dog.3 IgG is most frequently reported in the cat.1,7 IgM paraproteinemia occurs less frequently and is termed (Waldenström’s) macroglobulinemia. All typically manifest as a monoclonal protein spike (monoclonal gammopathy) on serum protein electrophoresis, although biclonal gammopathies have also been reported.3,6,8 Nonsecretory multiple myeloma is rarely reported in the dog.3

Other diseases may infrequently be associated with a monoclonal gammopathy and must be distinguished from multiple myeloma. Monoclonal gammopathy has been associated with lymphoma, ehrlichiosis, leishmaniasis, plasmacytic gastroenterocolitis, chronic pyoderma, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), and idiopathic causes.3,6

Because of their small molecular weight, Bence Jones proteins (light chains) are readily filtered through the glomerulus and are passed in urine.1 This is referred to as Bence Jones proteinuria (BJP) and is seen in 25% to 40% of dogs and 60% of cats with multiple myeloma.3 Traditional urine protein dipstick methodology does not detect BJP, necessitating use of more specialized testing, such as immunoelectrophoresis. With significant proteinuria, the sulfasalcytic acid (SSA) test will be positive with BJP.

Cryoglobulins are paraproteins that are insoluble at temperatures less than 37° C.7 Failure to detect cryoglobulins may occur if blood collection and clotting are not performed at body temperature to avoid precipitation and loss of these proteins. Clinical manifestations of cryoglobulinemia result from sludging of blood and obstruction of small vessels, particularly in the extremities, where blood may cool sufficiently to allow precipitation of cryoprotiens.6 Affected animals may present with cyanosis and necrosis of the skin of the distal extremities. Cryoglobulinemia has been reported in association with multiple myeloma in the dog, cat, and horse.7

5 What presenting signs are common in animals with multiple myeloma?

Skeletal involvement may be focal or diffuse. Focal osteolytic lesions are primarily seen in the dog2 and may result in lameness or pathologic fracture.1,3 An estimated 25% to 66% of dogs with IgG- and IgA-secreting tumors will develop osteolytic lesions. In contrast, dogs with IgM-secreting tumors only rarely present with osteolytic lesions.3 Sites most frequently involved are those of active hematopoiesis, including vertebra, pelvis, ribs, skull, and metaphysis of long bones.1,3 Diffuse skeletal lesions include osteopenia and osteoporosis, which may result from secretion of osteolytic factors, including osteoclast activating factor and parathyroid hormone–related protein (PTHrp), by neoplastic cells.1 Hormonal effects of osteolytic factors may contribute to the development of hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia is rarely seen in the cat but may affect 15% to 20% of dogs with multiple myeloma.2

Bleeding disorders are a frequent complication, affecting approximately one third of dogs with multiple myeloma. Clinical manifestations of hemorrhage may include epistaxis, petechiae, ecchymoses, bruising, gingival bleeding, and GI bleeding. A number of mechanisms may contribute to the development of hemostatic abnormalities. Thrombocytopenia may result from myelophthisis of the bone marrow. Platelet function may be impaired as a result of paraprotein-coating of platelets interfering with platelet aggregation. Paraproteins may also adsorb minor coagulation factors, causing a functional factor decrease of sufficient magnitude to prolong activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT).1 Paraprotein binding of ionized calcium may likewise contribute to functional hypocalcemia, further impacting the coagulation cascade.2

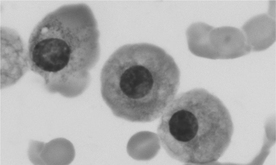

Hyperviscosity syndrome is a possible consequence of paraprotein secretion by neoplastic cells. Although it may develop with any type of paraproteinemia, hyperviscosity syndrome most often is a complication of IgM- and IgA-secreting myelomas, attributable to the higher molecular weight of these proteins and their ability to polymerize. Hyperviscous blood may sludge in small vessels, impairing delivery of oxygen and nutrients to tissues and predisposing to thrombus formation. Common manifestations include cerebral disease (seizures, ataxia, dementia), cardiac disease (cardiomyopathy, exercise intolerance, syncope, cyanosis), and ocular disease (sudden blindness, retinal detachment, tortuous retinal vessels, retinal hemorrhage). Hyperviscosity syndrome has been reported in 20% of dogs with multiple myeloma and less often in cats.1 Enhanced rouleaux formation, evident on peripheral blood smears, may signal the presence of hyperviscosity syndrome2 (see Figure 19-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree