Chapter 177 Pet Rodents

Many small rodents are commonly kept for companionship and enjoyment. This chapter provides information needed to diagnose and treat the most frequently encountered problems of mice, rats, gerbils, hamsters, guinea pigs, and chinchillas.

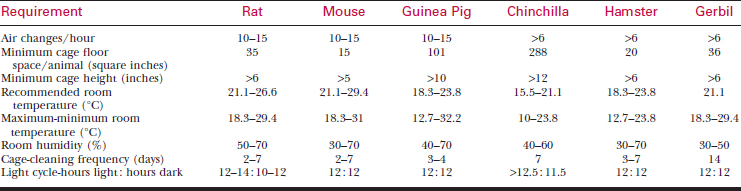

HUSBANDRY

Caging and Sanitation

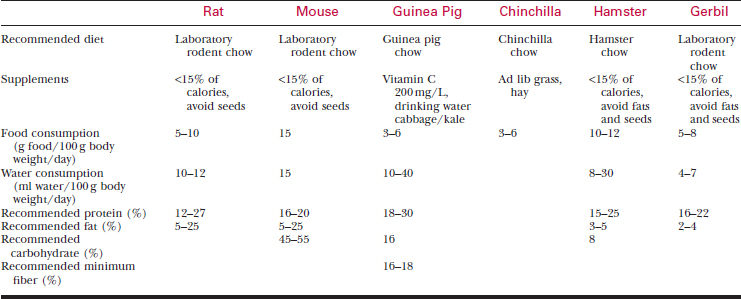

Nutrition

Feed pet rodents laboratory animal chow appropriate for their species (Table 177-2). Seed diets are deficient in protein and contain excessive fat.

Water

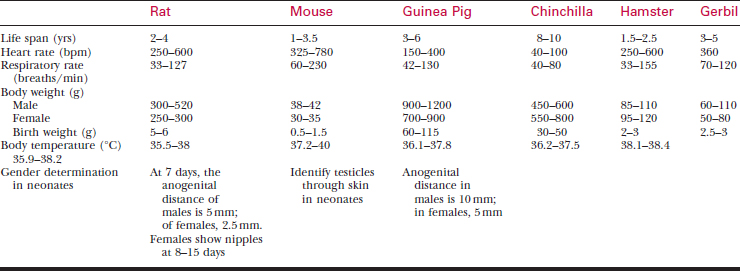

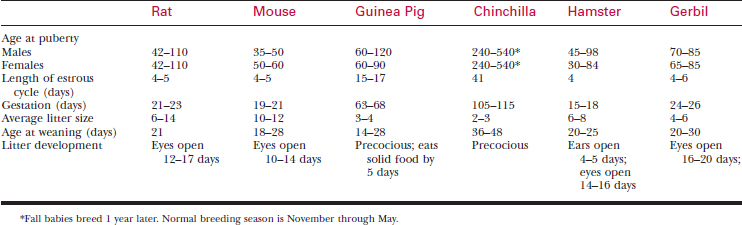

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A systematic history and physical examination are mandatory. Many disease syndromes are caused by poor husbandry. Pets that have been kept isolated from other rodents or acquired from a private breeder are less likely to harbor infectious disease than animals obtained from a pet store, laboratory, or wholesaler. See Table 177-3 for normal physiologic data.

Obtain the following information:

Examination of Patient and Environment

Evaluate the Cage

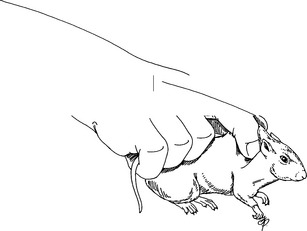

Restraint

Physical Examination

DIAGNOSTIC Tests

Blood Samples

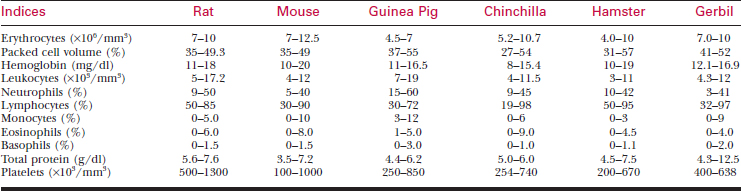

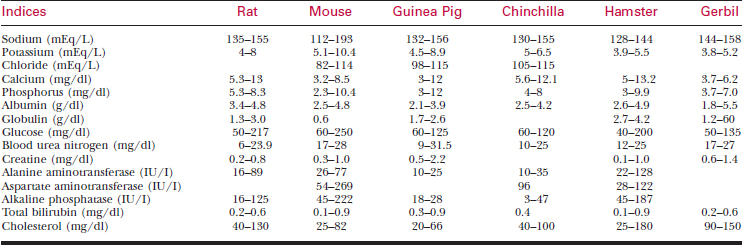

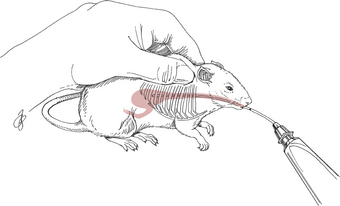

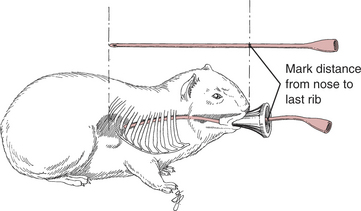

To bleed the tail, warm the tail with water or compresses to dilate the tail vessels. In large rats, perform venipuncture with a needle and obtain blood in the usual fashion. In smaller animals, lacerate the tip of the tail. Blood from the wound is collected as described previously. See Tables 177-5 and 177-6 for hematology and chemistry values.

ROUTINE PROCEDURES

Oral Medications: Nutritional Support

Incorporate oral medications into a treat, or administer them in liquid form. If the medication is palatable, administer it by placing the tip of a dosing syringe into the diastema.

Subcutaneous Injections

Intravenous Injections

For small rodents, give a bolus of fluids every 2-4 hours, followed by a diluted heparin flush. A pediatric IV pump is used for continuous infusion of fluids to larger animals. Maintenance of catheters in active animals is extremely difficult.

ANESTHESIA

Premedication and Patient Preparation

Inhalation Anesthesia

Induction

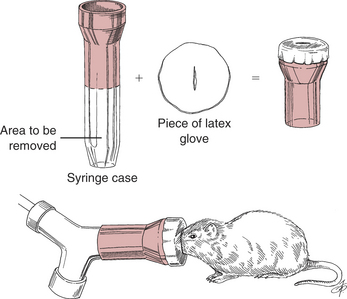

Induce gas anesthesia using small face masks purchased from laboratory supply houses or make them from syringe cases and latex gloves (Fig. 177-7). Induction in an anesthetic chamber is also possible.

The risk of this behavior is reduced by premedication with tranquilizers, initial induction with nitrous oxide with later addition of primary anesthetic gas after relaxation, and low induction settings. Changes in respirations, especially erratic or apneustic patterns and decreased respiratory rates, indicate deepening anesthesia.

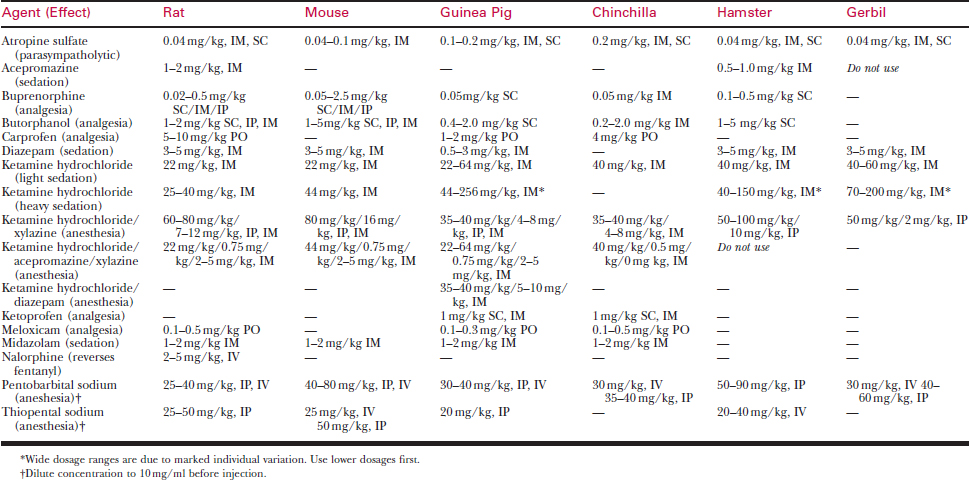

Injectable Anesthesia

Doses and routes for injectable anesthetics are listed in Table 177-7. Needed doses for injectable anesthetics are tremendously variable among species and individuals. Most injectable anesthetics provide safe sedation for minor procedures, but very few induce a safe surgical plane of anesthesia on a consistent basis.

SURGERY

Hemostasis

Pain Management

Administer postoperative analgesics to all rodents undergoing surgical or dental procedures. Common analgesics include buprenorphine, butorphanol, ketoprofen, carprofen and meloxicam. See Table 177-7 for dosages.

Common Procedures

The most common surgeries are laceration repair and removal of dermal or SC masses.

Castration

Technique

Dental Procedures

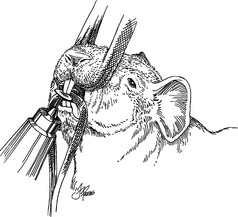

Incisors can be trimmed with nail trimmers, but this technique often fractures the tooth, causing abscesses of the root. Instead, use a high-speed dental burr or a flat cutting disk on a Dremel hand tool. Trim molars with a high-speed drill or pediatric rongeurs. A mouth speculum that deflects the tongue and other soft tissues is essential to prevent lacerations and provide working space (Fig. 177-8). Intubate the trachea to prevent aspiration pneumonia when working on molars.

If a tooth is abscessed, extract both it and the occlusal tooth.

MOUSE

Dermatology

Ectoparasites

Ectoparasites usually are found in new acquisitions.

Dermatophytosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree