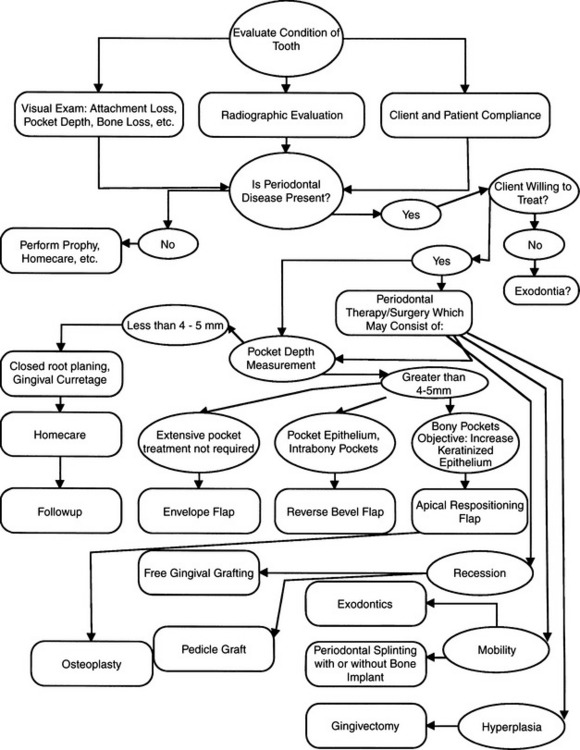

Chapter 5 Periodontal Therapy and Surgery

GENERAL COMMENTS

Professional prophylaxis (recall intervals, chlorhexidine brushing before prophylactic treatment, ultrasonic subgingival instrumentation, home care advice regarding disruption of flora).

Local delivery systems (bioadhesive tablets, subgingival biodegradable syringe applied and implant products).

Osseous regeneration and augmentation (guided tissue regeneration, GTR), bone grafts, bioactive implants, enamel matrix derivatives).

• It is important not to discard traditional effective modalities as we incorporate newer techniques.

• Patients with foul breath and advanced periodontal disease are often brought in for teeth cleaning. In these cases, more than dental prophylaxis or a simple cleaning is necessary to restore gingival health. The additional treatment may be broadly termed periodontal therapy. Client communication in this case is important: the client should understand that the patient’s condition has progressed beyond gingivitis to periodontitis and the treatment will not be a simple teeth cleaning, but periodontal therapy. Treatment for this patient will, therefore, take additional time, most likely require aftercare and follow-up, and will result in higher fees. Because of this, it is advisable to perform a preliminary examination, provide the pet owner with a written fee estimate, and establish with the owner the level of care desired. In this way a tentative treatment plan, anticipated expenses, and prognosis can be communicated to the client. The written information presented to the client should also include the possible need for extraction of teeth that can’t be salvaged.

• In otherwise healthy patients that have grade 3 and 4 periodontal disease and in medically compromised patients that have grades 2 to 4 periodontal disease, antibiotics should be started before periodontal therapy or surgery to establish a blood level.1–3 Preferred treatment is an antibiotic by injection 1 hour before surgery.

• A broad spectrum bactericidal antibiotic such as ampicillin or amoxicillin may be used in most cases. Some cases require treatment with antibiotics selective for gram-negative organisms, such as cephalosporin-based agents, enrofloxacin, or combinations of antibiotics. Clindamycin hydrochloride (Antirobe) and amoxicillin trihydrate/clavulanate potassium (Clavamox) have been used successfully in the oral cavity. Cephalexin and metronidazole are also commonly used antibiotics effective in orofacial conditions in dogs and cats.4 Tetracycline has been added to the list of drugs used for periodontal therapy by respected researchers.5

• Antibiotics are an adjunct to treatment and prevention of secondary infections, not a cure for periodontitis, although it is often a disease associated with infection.

SYSTEMIC DISEASE AND PERIODONTAL INFECTION

• One concept that has been a bit misunderstood in veterinary dentistry is “the theory of focal infection.” Perhaps we would be more comfortable thinking of it as the “theory of distant infection.” Current concepts in human dentistry today, of “periodontal diseases as localized entities affecting only the teeth and supporting apparatus, is oversimplified and in need of revision. Rather than being confined to the periodontium, periodontal diseases may have wide-ranging systemic effects … periodontal infection may act as an independent risk factor for systemic disease and may be involved in basic pathogenic mechanisms of these conditions. Furthermore, periodontal infection may exacerbate existing systemic disorders.”6

• Historically, Hippocrates is said to have reported the cure of arthritis after removal of a tooth.7

1920: C. Edmund A. Kells (founder of dental radiography) initiated reasoning that began to prevail, claiming that indiscriminate extraction of teeth to cure focal infections was “the crime of the age” and recommended that dentists refuse to operate upon physicians’ instructions to remove teeth needlessly.10

• This seems to be the crux of the problem. The initial concept in human medicine was that illness in various parts of the body could be cured by extracting teeth and performing tonsillectomies, but this could not be supported statistically. Nevertheless, systemic health is affected by chronic periodontal infection. In humans, a negative impact of oral infection on systemic health has been documented, from the entry of oral microorganisms or their products into the bloodstream. Research cites that bacteremia is common, and gingival inflammation can be the source of significant microbial entry into the bloodstream.11 Additionally, the pathogenesis of bacterial pneumonia in adult people primarily involves aspiration of bacteria that colonize the oropharyngeal region into the lower respiratory tract and failure of the host defense mechanisms to eliminate the contaminating bacteria, which subsequently multiply and cause infection.12 Gram-negative bacilli, such as enteric species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can be cultured from the subgingival flora of patients with periodontal disease.12 Bacterial migration can be provoked by mastication and oral hygiene procedures. The extent to which bacteremia of oral origin occurs appears to be related directly to the severity of gingival inflammation.11 This concept represents a distinct mechanism by which these bacteria may gain access to the systemic circulation. Researchers of human dentistry report that there is little doubt that, under certain circumstances, microorganisms can move from one area of the body to another to establish their customary pathology in another locale.13 They cite that “bacteria metastasize to the heart, brain, kidney, liver, joints, gastrointestinal tract, and skin from other areas of the body, including the mouth. The pathways for the dissemination of infection are by direct spread or by blood or lymphatic metastasis of the infecting organisms, their toxic products, or tissue immunologic reactions to the organisms or their products.”14 Research in veterinary medicine is sparse on this subject, but cases of distant infection that originated in the mouth have been cited,15 and evidence is strong that the same phenomenon seen in people is seen also in animals.16

Objectives

• Periodontal therapy has three principal objectives: (1) pocket reduction or elimination of the soft and bony lesions, (2) eradication or arrest of the periodontal lesion, with correction or cure of the deformity created by it, and (3) alteration in the mouth of the periodontal climate that was conducive or contributory to allowing periodontal disease to become established, creating a more biologically sound environment.17 We cannot cite one pocket depth for all cats and dogs as being the point at which a periodontal depth is considered pathologic. In a domestic cat 1.0 mm is an abnormally deep gingival sulcus and, whereas 2 to 3 mm might be the outside limit for a normal gingival sulcus depth in a medium to large breed dog, 4.0 mm might be considered normal in a St. Bernard. To keep normalcy in perspective, the healthy gingival attachment is found in very close proximity (within 1.0 mm) of the cementoenamel junction. Attachment measurements greater than this should be noted as attachment loss, and treatment for this pathologic condition should be planned accordingly.

ROOT PLANING: CLOSED TECHNIQUE

General Comments

• Root planing is the process whereby residual embedded calculus and portions of the necrotic cementum are removed from the roots to produce a clean, hard, smooth surface that is free of endotoxin.18

• The objective, whether performed with specially manufactured thin ultrasonic periodontal tips (described later in this chapter) or by hand instrumentation, is to render the root surface biologically acceptable to the soft tissue wall of the periodontal pocket without causing unnecessary loss or damage to hard or soft tissues.

Indications

• Presence of periodontal pocket of less than 5 mm in the dog and 1 to 2 mm in the cat. This does depend on relative tooth size and normal sulcus depth.

Contraindications

• Pockets deeper than 4 to 5 mm; because of the inability to access the base of the pocket, the subgingival bacterial plaque cannot be removed. When this is the case, open flap surgery should be considered.

Equipment

• A selection of curettes (a sharp instrument is important). It may be necessary to sharpen the instrument during the procedure to ensure a sharp edge at all times, to prevent burnishing the calculus, which creates a greater nidus for periodontal disease.

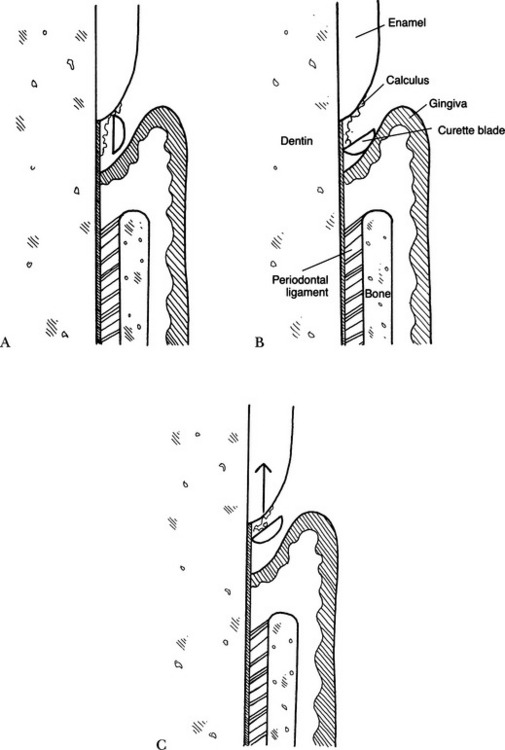

Technique

• The patient should receive a preoperative antibiotic if pus is present in the pocket or if the patient has any other systemic disease.

• A routine, systematic approach should be used on each quadrant and on each tooth. Specific curettes are selected because of their ability to reach to the depth of the pocket and adapt to the tooth surface.

• The blade of the instrument is inserted gently in the closed position; that is, the face of the instrument moves parallel to the tooth (Fig. 5-1, A). This allows the positioning of the curette apical to the calculus (often called the exploratory stroke).

• The blade of the curette is positioned against the root surface (adaptation) and opened (Fig. 5-1, B).

• The opened blade of the curette is withdrawn from the pocket in an oblique manner while applying pressure (known as the working stroke) (Fig. 5-1, C).

• Root planing is performed using a curette with overlapping strokes in horizontal, vertical, and oblique directions (also known as cross-hatching) (see the later section on gingival curettage). This may require additional cleaning strokes after all calculus has been removed, to obtain a smooth surface, being careful not to gouge the root surface. Subgingival root scaling becomes root planing after deposits have been removed from the surface and the scaling technique is employed to smooth the root surface.

• As root planing is being performed, an assessment must be made, using a dental explorer, regarding the nature of the dental deposits and tooth surface. This evaluation determines how much pressure and in what direction the working strokes should be made. Closed root planing by curette is a complex and precise coordination of visual, mental, and manual skill that makes subgingival instrumentation one of the most difficult of all dental skills. The success of the procedure rests on the operator’s familiarity with and choice of instrument for each periodontal site, the maintenance of that instrument, and the skill with which the surfaces are debrided as atraumatically as possible.

• The object of calculus removal is to fracture it cleanly away from the tooth surface, not to shave, wear down, or smooth the deposit (referred to as burnishing).

Complications

• Deposit cannot be removed. The solution is to reposition the blade to remove less calculus per stroke, change the angle and direction of pull of the instrument, change instrument, or sharpen the instrument. Too little pressure can cause the instrument to glance over the deposits and to smooth down the deposits rather than remove them. As these deposits become smoother, they also become harder to detect and remove.

• The surface is still rough after planing. The solution is to check the instrument for sharpness and replane or, if too much force has been applied causing an uneven root surface known as ruffling, to use light, smooth strokes.

• Failure to plane the root in the apical portion of the pocket leaves bacterial plaque and causes an increase in periodontal pocketing and subsequent periodontitis and bone loss.

• Some root surfaces do not lend themselves to thorough root planing, including the maxillary first and second molar. In this case, careful instrument selection and adaptation is important. Failing to do this, it is better to perform a periodontal flap procedure or extract the tooth.

• Hemorrhage may limit visibility. Limited visibility may require the use of pressure, water irrigation, and suctioning during the procedure.

• It may be difficult to access the root surface, particularly in areas of exposed furcations that may be large enough to allow accumulation of plaque and calculus, but too small and inaccessible to permit thorough root planing. Microultrasonic instruments may be the solution, due to their thinner tips and type of movement.

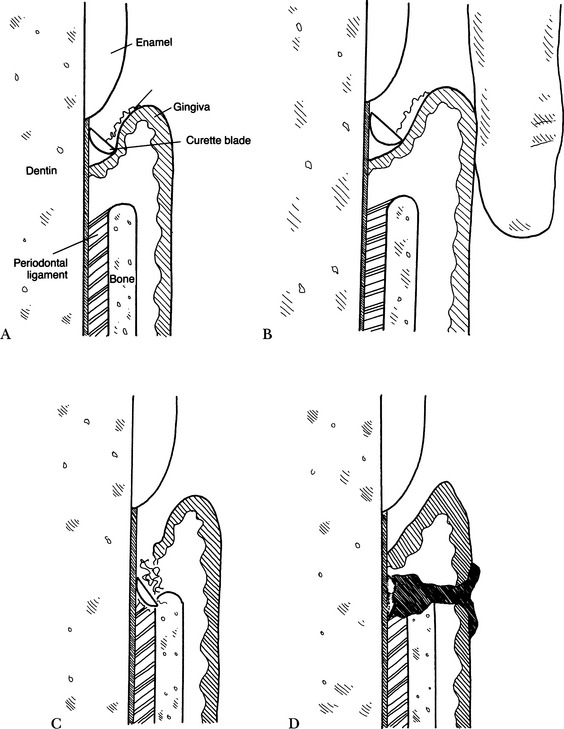

GINGIVAL CURETTAGE

General Comments

• Usually is performed in conjunction with root planing; called coincidental curettage when performed adjacent to teeth being root planed.

Indications

• Removal of sulcular epithelium, inflammatory infiltrate, subgingival bacteria, and invasive bacteria.

Technique

• Performed with the curette held in the reverse position from normal scaling; this places the blade against the soft tissue for epithelial removal (Fig. 5-2, A).

• A finger against the gingiva may be used to support gingival tissue during curettage (Fig. 5-2, B).

• Gentle compression applied for several minutes to aid readaptation of tissues to the teeth and to control hemorrhage.

Complications

• Deepening of the periodontal pocket may be caused by placing the curette too deeply into the pocket and tearing or cutting the periodontal ligament or perforating the junctional epithelium at the base of the pocket (Fig. 5-2, C).

• Plaque or calculus left in the pockets—the superficial and coronal tissue heals, and the pocket shrinks and tightens, trapping mineralized bacterial plaque and calculus and resulting in increased chronic lysosomal release, tissue breakdown, bone loss (periodontitis), and possible abscess, which further prevents healing (Fig. 5-2, D). As part of the process, the tissues should be irrigated with water or an antimicrobial irrigant to cleanse the area further.

ULTRASONIC PERIODONTAL DEBRIDEMENT

General Comments

• There has been a paradigm shift from the traditional emphasis on treatment of the tooth and root surface in periodontal therapy to a focus on establishing and maintaining healthy periodontal tissues.

• Removing bacterial plaque and endotoxins and removing plaque-retentive deposits and surfaces are the main goals of periodontal debridement.20

• This procedure may involve three phases: supragingival debridement, subgingival debridement, and plaque removal.

• This procedure removes less cementum than manual root planing with curettes; this creates less dentinal hypersensitivity and less chance of overinstrumentation and gouging of tooth and root surfaces.

• Specialized tips can be used in and around furcations to improve removal of bacterial colonies and calculus, especially in the dome areas of furcations, previously inaccessible.

• This procedure can be performed more quickly and more effectively, with less anesthesia time and with less effort, than manual root planing.

• Antimicrobial irrigants (dilute chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine solutions) can be added to the water source of some ultrasonic scalers to aid in plaque reduction and reduction of bacterial aerosolization.

Technique

• The patient’s mouth is lavaged with a dilute chlorhexidine solution to reduce external bacterial counts.

• Supragingival calculus and plaque are removed with the broad tips and with light, rapid sweeping motions over the surface of the crown.

• The ultrasonic or sonic scaler is fitted with the long, thin periodontal tip. The power setting is reduced and tuned properly, and the water spray is adjusted.

• The instrument tip is used similarly to a probe, placed in the sulcus or pocket parallel to the long axis of the tooth surface.

• The side of the tip of the instrument is used with a paintbrush-like motion over the root surface in diagonal strokes. The pressure is very light and rapid strokes are used (also referred to as feather-light touch).

• Removal of subgingival calculus starts coronally and works apically, using the end of the tip in a gentle tapping motion against the calculus to shatter and remove it.

• After calculus removal, the tip is used in a broad sweeping motion in the sulcus or pocket, to remove bacteria from the tooth surface. The instrument tip must touch every square millimeter of root surface; therefore, overlapping or cross-hatching strokes are most desirable.

• A curette or explorer is used to evaluate the smoothness of the root surface, because these delicate instruments provide an excellent tactile evaluation.

PERIOCEUTIC TREATMENT

General Comments

• A perioceutic agent is a medication designed to be delivered into a periodontal pocket for local treatment of periodontal disease.

• Doxycycline has been found to provide local control of the microorganisms prevalent in periodontal disease.

Materials

• Doxycycline 8.5% (Doxirobe, Pfizer, New York, NY). This product comes in a packaged pouch with two syringes and a 23-gauge, 1-inch blunt cannula. Once mixed, the product becomes a solution of doxycycline hyclate equivalent to 8.5% doxycycline activity.

Technique

• Periodontal therapy with root planing or periodontal debridement should be performed. The root surface and pocket should be completely free of calculus, plaque, and other debris. The product should be applied only after the teeth and pocket are clean.

Step 2—Beginning with syringe A, express the contents into syringe B, mixing the product by pushing the syringes back and forth approximately 100 times until the contents are mixed completely.

Step 3—Deliver all of the contents of the syringes, and remove syringe B from A and replace with the supplied 23-gauge cannula.

Step 4—Gently place the cannula 1 to 2 mm below the gingival margin of the tooth to be treated, and inject the mixture while moving the cannula in the pocket. The pockets should be filled to the gingival margin.

Step 5—Lavage with a few drops of water supragingivally to hasten the solidification of the material.

PERIODONTAL SURGERY

• Various modalities may be employed when performing periodontal surgery. The time-honored and traditional modality of scalpel surgery, using various sizes and shapes of scalpel blades, is the most commonly used modality. Electrosurgery and radiosurgery have been used frequently in recent years. More recently, laser surgery has been touted as a “painless” surgical technique and a way to perform high-technology surgery. There are pros and cons for each modality. Laser units are expensive and, in the opinion of the authors, in most instances do not offer significant advantage over scalpel and electrosurgical techniques to justify the increased cost to the clinic and the client. Surgical procedures in this text will be described with scalpel surgery, because that is what is employed in most veterinary offices. Readers who prefer other surgical modalities should substitute the use of scalpel with that of their own instruments. Following are brief descriptions of the three modalities and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Sharp Dissection

• Scalpels, periodontal knives, periosteal elevators, excavators, bone curettes, and scissors are the most common sharp instruments used in periodontal surgery. They work well, are easily handled by general practitioners, and are the instruments favored by the majority of veterinary clinicians.

Electrosurgery and Radiosurgery

• Compared with electrosurgery, electrocautery uses low frequency, low wattage, and low heat, which creates incandescent heat, causing a third-degree burn that is harmful to tissues and can cause bone loss.

• Electrosurgery uses a frequency of 2.0 MHz or higher. Radiocautery uses higher frequency (3.0 to 4.0 MHz) and is relatively atraumatic.21 Fully rectified filtered waveform is used for cutting soft tissue with a pure continuous flow of high-frequency energy to provide micro-smooth cutting. There is minimal amount of lateral heat, and it can be used close to bone. Partially rectified waveform is used for coagulation of soft tissue, desensitizing dentin and cementum from cervical erosions, bleaching endodontically treated teeth, and drying and sterilizing endodontic canals.22

Instruments

• Electrosurgical unit: Ellman International (Hewlett, NY) and Summit Hill Laboratories (Tinton Falls, NJ) supply the popular units in veterinary oral surgery.

Laser Use in Periodontal Surgery

General Comments

• The lasers most commonly used in human periodontal dentistry are the carbon dioxide (CO2) and the neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG).23 Diode lasers are also used in veterinary dentistry.

General Objectives

• Atraumatic, bloodless, nonpainful surgery with a more rapid recovery to former activity than with other surgical techniques.

Reported Veterinary Dental Uses

• In cats with severely inflamed gums. Resurfacing of the gingiva to shrink the swollen gum tissues and reduce inflammation, using 2 watts continuous mode or, preferably, a superpulsed mode.

• Cats with very superficial feline odontoclastic resorptive lesions (FORLs), but no radiographically seen root resorption, are treated with superpulsed mode, or even continuous mode. Use caution to avoid charring the tooth and pitting the enamel or dentin. Use 2-watt setting after first painting the tooth with a thin layer of stannous fluoride. In most cases the procedure slows progression of the FORLs and improves the patient’s comfort level.

• Incisional and excisional biopsies. Initially the laser is used in a cutting or focused mode, held perpendicular to the tissue, and used to follow the surgical outline. A tissue forceps is then used to raise a border of the outline, and the lesion is undermined with the laser in an elliptical fashion. The surgical site is left to granulate.

• Partial or full ablation of small, slightly raised benign lesions. Use CO2 in a defocused mode for papillomas, fibromas, pyogenic granulomas, and hyperkeratotic lesions of the buccal mucosa and tongue.

Precautions and Disadvantages

• Avoid reflecting the beam on instrument surfaces, because it could injure adjacent tissues and eyes of operator.

• Respected periodontal authorities in human dentistry are concerned regarding its efficacy: “At present, the use of lasers for periodontal surgery is not supported by research and is therefore discouraged. The use of lasers for other periodontal purposes, such as subgingival curettage is equally unsubstantiated and is also not recommended.”23

Equipment

Carbon dioxide laser

• Not a solid state laser; it consists of mirrors and gases (AccuVet NovaPulse 20-watt CO2 surgical laser, ESC Sharplan, Norwood, Mass.).

• Cuts optically, but coagulates thermally, producing some char. Wipe away the char with a wet physiologic saline solution (PSS) gauze to reduce slough.

• Less pain than scalpel or electrosurgery. It seals nerve endings, vessels, and lymphatic structures.

• Completely absorbed by water, but not by hemoglobin or oxyhemoglobin. Will never go through a wet sponge (this is good), but function is compromised in hemorrhagic conditions.

Diode laser

• Produces laser light when electrical current is passed through the diode chips (Vetroson, 810NM, and 815NM Twilite model, Summit Hill Laboratories, Tinton Falls, NJ).

• Flexible fiber fits down an endoscope. May be used in all areas of the body. Trim fiber before use.

A Final Thought About Lasers

• Martindale reported that BioLase developed the Waterlase, based on water technology, and predicts that it will replace all of the above, because each operates within specific but different wavelengths and works best in specific tissue and moisture environments. Early in 2002 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration sanctioned Waterlase for both soft and hard tissue work in root canals and jaw surgery. It has the advantage that it does not shoot a laser directly onto the tooth or gums. Instead, the beam energizes a spray of water droplets, which blasts the surface and scours away diseased or decayed tissue. It can switch between soft and hard tissue wavelengths.

MANDIBULAR FRENOPLASTY (FRENECTOMY OR FRENOTOMY)

Indications

• Gingival recession or pocket formation and detached gingiva on the distal side of the lower canine teeth, enhanced by the presence of the frenulum.

Technique

Step 1—The attachment of the frenulum to the mandibular gingiva near the first premolar is cut horizontally with scissors or scalpel (Fig. 5-3, A).

Step 2—The incision is extended with sharp or blunt dissection into the frenulum to relieve the pull of the muscular attachments. The lip will relax laterally when the attachments have been severed completely (Fig. 5-3, B). A diamond shape is created by the cut surfaces.

Step 3—A suture is placed to bring the mesial and distal edges together (Fig. 5-3, C). Several simple interrupted, absorbable sutures are placed to prevent reattachment (Fig. 5-3, D).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree