Having a healthy animal welfare account requires maximising welfare credit and minimising welfare debt. Harms should be minimised wherever possible (just as it is not sensible to borrow more than you need). Some harm may be necessary in order to gain bigger welfare benefits, for example when surgery causes pain but cures the animal of a painful condition (which we can think of as an investment). At other times, welfare benefits can be obtained only by taking certain risks, for example where surgery risks causing neuromas or phantom limb pains (Figure 1.1), and we may have to speculate to accumulate.

This approach suggests that we should make every effort to cause good welfare while avoiding causing harms. We could think of this in terms of our overall impact on animal welfare, a sort of animal welfare footprint. But it seems better to think of it as each leaving a legacy – good or bad – on animal welfare. Veterinary work provides great opportunities to leave a valuable and significant legacy, and this book may provide some additional suggestions to help readers do even more than they already do.

Whether we consider animal welfare to relate to animals’ feelings, their treatment, their biology or their lifestyle, we can be confident that these things are important for animals in some way. This makes veterinary professionals well placed to determine and to achieve animal welfare goals as well. We have an understanding of biological science, interact daily with the pet-owning public and with the animals themselves, and are respected sources of advice in the community. The different people within veterinary practice and professions have different roles and different opportunities to help animals. But we all face similar situations and have the same aims as veterinary professionals.

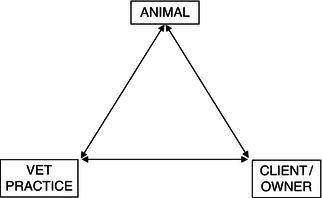

In this role as veterinary professionals, we face a number of pressures and tensions. We see welfare issues every day, and many are recurrences of seemingly unending problems, despite our good work. We are personally involved in and affected by the pressures, tensions and conflicts we experience. These can cause stress, disillusionment and anger. Some people even leave the veterinary professions, and this is both terribly sad for them and a great loss for animals – especially if it is some of the most welfare-concerned people who are vulnerable to these stresses. We have relationships not only with patients but also with clients (Figure 1.2). In many cases, achieving our animal welfare goals helps people. It can help owners who want their animals’ lives, health or behaviour to be improved. It can also help veterinary professionals by reducing the personal and moral stresses and improving profitability. In other cases, we have to balance the conflicting demands. As individual practitioners, we have to balance our wish to achieve our animal welfare goals with client requirements, legal constraints and public concerns. And as professionals, we have to balance being advocates of animal welfare with other goals such as benefitting human society and helping each other. This book looks at how we can best improve animal welfare while respecting these constraints.

We also face conflicts between animals. For example, concern for our patients would lead us to perform caesarians where necessitated by breed conformation. But performing such caesarians perpetuates the problem and allows those conformational traits to continue, leading to increased need for caesarians. In this case, veterinary professionals are both part of the solution and part of the problem. Maintaining a healthy welfare account requires balancing these concerns. In addition, when we do cause harm, either deliberately or through helping our patients, we can improve our welfare account by paying something back. For example, if we perpetuate poor husbandry or breeding (even with the best intentions), then we should offset that harm through proactive efforts to promote better practices.

We can maximise our animal welfare account and solve welfare dilemmas by considering many important issues, including the accountability that veterinary professionals have towards animal welfare (discussed in Sections 1.2 and 1.11), our responsibilities (Sections 1.3 and 1.4), the use of science (Section 1.5) and ideas of what is good for animals (Sections 1.6, 1.7, 1.8, 1.9 and 1.10).

1.2 Animal Welfare Accountability

Veterinary professionals have a special role within society that makes their animal welfare accounts especially important and prominent. During the veterinary profession’s 250 years, it has become increasingly prominent as a force to improve animal welfare and is increasingly held to account for how it treats animals and how animals are treated by society as a whole. Each veterinary professional has a duty to play their part in helping their profession to fulfil its responsibilities to society.

Modern veterinary practice can be traced back to horse marshals’ and farriers’ development of medical treatments and surgical procedures, such as firing, bleeding, castrating and tail-docking. By the eighteenth century, such therapies were routinely applied to cattle, sheep and pigs as rising human populations and breeding strategies made individual animals increasingly valuable.

Veterinary practitioners gained a prominent position in safeguarding animal health, but they were far from a profession. This waited upon scientific and medical developments disseminated through education beginning with the first veterinary course in Lyon in the 1760 s, followed by others in Alfort, Turin, Copenhagen, Vienna, Dresden, Gottingen, Budapest, Hannover, Padua, Skara and London, and later schools in Toronto, Montreal, Ithaca, Iowa, Santa Catalina, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and Olinda.

Professional regulation addressed the opportunities for charlatanism (Porter 1992; Hall 1994), with the establishment of professional bodies such as the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) in 1844, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) in 1863, the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA) in 1949 and the Brazilian “Conselho Federal de Medicina Veterinária” (CFMV) in 1968. These provided society with a guarantee of knowledge, ability and professionalism.

These developments paralleled changes in society at large that increased the respect for animals. Political changes led to widening social progress and protection of vulnerable groups such as slaves, women and children. Scientific discoveries highlighted the phenotypic and genetic similarities between humans and other animals. Animals began to gain legal protection, with increasingly progressive laws against specific cruel practices, abuse and vivisection.

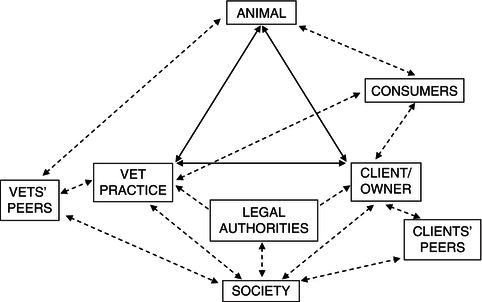

By the start of the twentieth century, veterinary professionals had a number of societal responsibilities based not only on their key relationships with owners and patients, but on their wider societal relationships with other animals, governments, other veterinary professionals and society at large (Figure 1.3). Alongside veterinary professionals’ primary relationships with animals and clients, the profession also had other vital duties to wider society, such as protecting public health. In addition, the professional status of veterinary practice created new responsibilities for individual practitioners towards their profession and to society.

Since the early twentieth century, there has been a golden age of developments within veterinary science, often paralleling developments in human medicine such as antibiotics, fluid therapy and painkillers and other forms of analgesia. Therapies were often developed on animal experimental subjects, applied to human medical patients, and then adapted to animal medical patients. These developments stimulated the development of veterinary disciplines such as imaging including ultrasound and radiography, immunology to study the bodies’ reactions to disease, epidemiology to study the spread of disease, molecular biology to understand the body on a subcellular level, genetics and chemotherapy.

On the one hand, technological developments allowed higher levels of care and, combined with increased treatment of companion animals (Figure 1.4), increased the transference of techniques and protocols from human medicine. On the other hand, technological developments made it feasible to keep animals in high-production systems. Veterinary professionals could prescribe pharmaceuticals, such as vaccinations and antimicrobials (e.g. penicillins), and operations, such as tail-docking and de-beaking, in order to address system health problems. In some cases, scientific developments went further and advanced methods to increase productivity, such as the use of artificial insemination and growth promoters like bovine somatotropin.

Figure 1.4 The increased importance of companion animals has altered veterinary work. (Courtesy of David Carpenter.)

Such changes in modern farming methods prompted a reconsideration of animal welfare issues, which were eloquently and influentially raised by critiques of widespread husbandry practices such as Ruth Harrison in the 1960s and Peter Singer in the 1970s. This led to the creation of animal welfare science as a discipline, promoted especially by the activities of Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (UFAW) since the 1920s, the launch of the Brambell Report in 1965 and the establishment of the UK Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC) in 1979. Animal welfare is now an established scientific subject, with its own international journals (e.g. Animal Welfare), learned organisations (e.g. UFAW) and academic courses. The development of animal welfare science resulted in a distinction between animal welfare and animal health. Animals could have their basic physiological and medical needs met despite suffering significant welfare compromises such as frustration, boredom, loneliness and anxiety.

Some people feel the veterinary profession now has a rather poorly defined place in contemporary animal welfare debates due to the implication of practitioners in intensive farming, the veterinary profession’s focus on health matters and the separation of health and welfare. Many individual veterinary professionals have contributed considerably to the development of animal welfare science and to policy-making. But they are often a few voices amongst many, and in many countries they lack the authority to provide the determinative viewpoint or the most progressive drive on animal welfare issues. Indeed, in many countries the profession is losing its status as an animal welfare authority.

The risk of losing this status comes while the public, and many veterinary professionals, still appear to consider veterinary professionals’ role as being to promote animal welfare. Prominent members of veterinary professions have promised to do more for animal welfare and to concern themselves with wider concerns than only health. Several professional bodies have created structures for individual members to help them advance animal welfare through policy-making, education and specialisation.

The veterinary professions are therefore at a time of both high risk and great opportunity. Our development has provided us with a number of social accountabilities to owners, animals, society and each other. But our historical development can only describe what responsibilities we have had; it cannot prescribe what our responsibilities should be in the future. We have the chance now to decide our core responsibilities and what distinguishes our special place as a profession. Society, many owners and most individual practitioners appear to consider that this focus should be beyond animal health, farming productivity and public health. Society, owners and individual practitioners consider that we should be accountable for animal welfare.

1.3 Animal Welfare Responsibility

If everyone has an animal welfare account, then what particular responsibilities do veterinary professionals have? Veterinary professionals have the same general responsibilities to animals as other people but are more accountable because we have more opportunities to cause greater harms and fewer excuses because of our greater knowledge. But veterinary professionals also have duties that laypeople do not.

In many countries, the licence to practise as a veterinary professional is limited to certain people. This restrains other people from conducting potentially harmful procedures. This restriction is beneficial when it stops untrained people from conducting potentially harmful procedures or misusing drugs. But this restriction also places an additional responsibility on those who can provide procedures to do so when necessary, since nobody else can provide them. Such veterinary responsibilities come with our veterinary privileges.

Often veterinary duties are specific responsibilities towards our patients (Yeates 2009a). By taking patients into our care, we are undertaking to work towards maximising their welfare. We have particular duties to those animals, which should motivate us to look after them and provide a certain level of treatment. We have duties to owners who have entrusted their animals into the care of veterinary professionals with good faith that those animals will be looked after.

Veterinary professionals have social responsibilities because they have joined a profession where animal welfare concern is expected (Rollin 2006a). Animal welfare responsibilities might be explicitly implied by professional regulations or implicitly required by public expectations. Public expectations include those of society and of other veterinary professionals, whose cooperation and professional relationships are based on that assumption.

Some veterinary professionals specifically promise concern for animal welfare. In the USA, veterinary surgeons may swear the oath of the AVMA, which was recently changed to include a promise “to use my scientific knowledge and skills for the benefit of society through the protection of animal health and welfare, the prevention and relief of animal suffering …” (AVMA 2011). In Brazil, veterinary surgeons may swear the oath of the CFMV, which includes a promise to “apply my knowledge to scientific and technological development for the benefit of the health and welfare of animals …” (CFMV 2002). Veterinary professional bodies also often claim to look after animal welfare: by making such a claim, they undertake a responsibility to fulfil it.

Veterinary professionals also have a responsibility to care for animals simply because we care about animal welfare. Most applicants for veterinary courses and jobs are highly intelligent and motivated individuals, who could have chosen careers with shorter hours, less stress and better pay. Veterinary professionals have already made a choice to sacrifice their personal interests so that they are in a position to help animals. Veterinary surgeons have a responsibility towards animal welfare because they have taken that responsibility on.

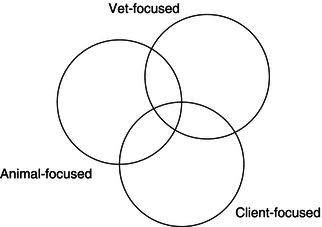

Veterinary professionals therefore have a duty to perform welfare-focused practice. This approach is an alternative to vet-focused practice, which considers the interests of oneself, one’s colleagues and one’s profession, or client-focused practice, which considers the interests of clients, although these three can overlap (Figure 1.5). Veterinary professionals do have duties to clients and themselves, but this book considers that good veterinary practice is predominantly welfare-focused. One is not a good surgeon simply by knowing where to cut. Being a good surgeon involves good decision-making, providing good analgesia and post-operative care and knowing when not to operate. The same animal welfare responsibilities apply in all areas of practice.

1.4 Legal and Professional Responsibilities

Our responsibilities to animal welfare are often underscored by our legal responsibilities. The law provides a backdrop for all our actions, and anxiety about legal consequences can cause unnecessary stress to many veterinary professionals. While this book cannot give legal advice for particular countries, it is possible to sketch certain types of rules that relate how veterinary professionals treat animals alongside the client-focused and owner-focused legal issues discussed in Section 2.2.

Some laws apply to governments and institutions that make decisions. Some countries such as India and Germany include animals in their constitutions. Some international agreements also mandate concern for animals, such as the Treaty of the European Union and the European conventions for the protection of pet animals and animals kept for farming purposes. These laws directly recognise animals’ status and prescribe a level of protection. Governments then make laws that apply directly to people, including many elements of criminal law. These laws are interpreted by judicial courts, which make specific decisions about particular cases, with the result that different animals may have inconsistent levels of legal protection.

Many laws proscribe things being done. In most, if not all countries, anti-cruelty legislation is amongst the first pieces of legislation that are brought in. Several countries’ laws prevent various negative outcomes, such as causing unnecessary suffering, killing animals without good reason, dog fighting or performing certain mutilations. Other laws prescribe positive outcomes, such as caring for an owner’s animals, mandating disease control or maintaining biosecurity.

Other laws require things to be done only under certain conditions. For example, many countries’ laws state that mutilations such as tail-docking can be performed only on certain animals by certain people using certain methods. Many countries permit experimentation on (vertebrate) animals only under a licence and following ethical review of proposed projects. Several countries require licences for breeding certain animals, owning pet shops, riding schools or boarding kennels or slaughtering an animal for public consumption. Some laws mean people need a licence to own certain animals, such as dangerous animals and farm animals. Often licences are given only under certain conditions, for example that people are trained or have appropriate facilities. More and more countries are requiring licences before people can own any animals at all.

Most countries with an established veterinary profession also have laws that restrict who can practise as veterinary surgeons or veterinary nurses. Often these laws require veterinary professionals to have certain qualifications (e.g. a recognised veterinary degree). Limiting the licence to practise has an additional benefit of allowing the regulation of veterinary professionals. This is often achieved by making membership of the profession conditional upon following certain rules, which are usually described in a deontology or code of practice. These professional rules may prohibit certain welfare-unfriendly procedures, such as kidney transplantation from live donors. They may make other welfare-friendly procedures mandatory, such as emergency first aid. They may also prescribe general approaches such as ensuring the welfare of animals committed to the veterinary professional’s care.

Laws and professional rules usually coincide with what society thinks acceptable or unacceptable (e.g. murder). Other laws coordinate action in ways that society thinks useful (e.g. which side of the road to drive on). Often our laws do not tell us what to do but allow a range of options from which we can choose the most acceptable. Consequently, most people follow the law most of the time.

Sometimes the law appears to conflict with what we think is the right thing to do for a particular case. However, this appearance is often misleading. Fortunately, courts often accept a reasonable excuse as a legitimate defence and many prosecutors only proceed when prosecution is in the public interest. For example, a stray animal may be presented in extreme suffering. Thinking only of a law against destruction of property would suggest it should not be given the euthanasia it needs. But the need to avoid unnecessary suffering should provide a legal defence against prosecution for reasonable efforts to prevent suffering. Veterinary professionals should not be overly concerned by possible legal ramifications. For example, it may be legitimate to euthanase a stray animal that is suffering only moderately but which is unlikely to be claimed and is unsuitable for rehoming or releasing.

Nevertheless, there may be cases where we might think the law is wrong. Laws may proscribe ways to improve welfare (e.g. stealing someone else’s animal) or permit actions that worsen welfare (e.g. shooting or irresponsible breeding). Sometimes following the law may lead to animal welfare compromises, and improving welfare would require breaking the law. Veterinary professionals have a vital role in evaluating the current laws and professional rules and suggesting improvements. This means that welfare-focused decision-making must look beyond simply analysing what our country’s law or professional body says.

1.5 Science

Veterinary professionals’ education and decisions are prominently based on knowledge generated by the sciences, including animal welfare science and veterinary science. Science is often described as a single way of thinking, but it actually uses several different methods. Hypothetico-deductive approaches start with scientists generating a general hypothesis about the world (e.g. that swans are white). From this, scientists generate more precise and testable hypotheses (e.g. that the next animal of genus Cygnus will reflect light of all visual wavelengths). They then obtain data that either support or refute that hypothesis. Inductive methods involve data being collected without any explicit, specific prior hypotheses and analysed to identify relationships such as risk factors. Both methods have advantages and disadvantages and are often combined.

Both hypothetico-deductive and inductive methods are based on a number of features that make them scientific. Both use relatively simple observations that are consistent between people, quantitative data analysed using standardised statistical methods based on agreed mathematical axioms. In this way, both use building blocks to work from simple agreed ideas to more complex conclusions, with which people should agree, using which should be repeatable in different situations and at different times.

These efforts to make science more reliable mean that science is seen as a way to obtain objective knowledge. Non-scientific beliefs can be inaccurate because they involve an invalid generalisation or because they are skewed. Beliefs involve an invalid generalisation when they are based on a limited number of observations, which relate only to specific, non-representative animals. Such beliefs can include those based on an owner’s personal experiences of their previous animals or a veterinary professional’s personal experiences of their previous cases. Beliefs may be skewed when they are influenced by individual biases, which alter a person’s interpretation of the observations. These include confirmation biases, where we tend to take more notice of observations that confirm what we already believe, self-interest biases, where we tend to be more ready to believe facts that we want to be true, and emotional biases, where our beliefs are affected by our emotions.

The objectivity of science makes it a valuable tool in decision-making, especially in determining trustworthy factual beliefs. Veterinary professionals should encourage the use of science in decision-making, both within evidence-based veterinary medicine and within veterinary and animal welfare policy-making, and it is good for decisions to be based on science. However, decisions should not – indeed cannot – be based only on science, for several reasons. Science also has its limitations, just like law.

In many cases, there simply is no scientific information. Some subjects are not studied because the results are obvious without the need for the study, some because they are not sufficiently interesting to scientists or funders, and some because they concern hypotheses or things that would be unethical to test. For example, it would seem wrong to study the effects of chainsaw injuries on cows. So we do not have any scientific data on bovine chainsaw injuries. Nevertheless, we can have a fairly confident belief that chainsaws will cause tissue damage, haemorrhage and pain behaviours, based on our personal experience of similar injuries and common sense. Such absences of data mean we cannot say that decisions should be made only when scientific data are available, although this position is expressed quite often by people trying to preserve the status quo. In many cases, we can – and should – make decisions about how confident we are that a treatment will work, often based on experience or understanding of physiology, pathology and pharmacology or simple common sense.

Even where scientific data are produced, studies are not always 100% accurate. Studies can involve errors, chance effects, subconscious biases (e.g. in interpreting data) or even conscious manipulation (e.g. publication biases). Studies may therefore disagree, and we have to choose which data we use, and this choice is often a non-scientific choice. This means it can be skewed or biased, and this is especially dangerous if the final decision is then presented as completely scientific. There is also a danger that people dress up facts to look more scientific, for example by presenting them pseudo-scientifically as numbers or as surveys. So, even where data are available, we must use science appropriately and critically.

Even where there are reliable scientific data, there can be limits to what those data can prove. Results can demonstrate statistical probabilities about the animals that were studied in the experiment or study (often compared to pure chance, e.g. in “p” values). However, these probabilities may not apply to other animals in other situations (e.g. other species or individuals). Decisions whether to extrapolate are yet more non-scientific decisions about whether that extrapolation is justified.

Furthermore, there are some things that science cannot prove because they are outside of scientific methodologies. Three examples are especially important for us: death, feelings and the future. If animal welfare science assesses what happens to an animal (while it exists), then it cannot study what does not happen to the animal while it no longer exists. If science assesses observable events, and animals’ feelings are unobservable, then science cannot prove that animals have feelings. If science describes what occurs in the past, then it cannot describe what will occur in the future.

Veterinary professionals therefore need to use other methods to convert scientific information into animal welfare assessments and decisions. This inevitably – and beneficially – involves using both emotional processing and logical, comprehensive and critical reasoning. Fortunately, these are skills that veterinary professionals develop. We have an understanding of the limitations of science, an appreciation of probability and uncertainty, an ability to tailor evidence to individual cases and experience to make future assessments. These are all valuable skills that go beyond science that veterinary professionals can possess.

1.6 Achieving and Avoiding

Veterinary professionals have the skills to use information, reasoning and judgement to work out what is worth achieving or avoiding. These decisions are an essential part of animal welfare assessment and clinical decision-making.

Many things are worth achieving or avoiding for other humans. We often think we should help, or at least not harm, our clients, such as by giving them value for money. We often think we should help, or at least not harm, other humans, such as by minimising public health risks. Treating animals can provide worthwhile human benefits such as companionship, financial profit, experimental data and food, alongside human harms such as emotional stress, financial costs, aggression and zoonotic diseases that humans can catch from non-human animals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree