CHAPTER 42 Parturition and Dystocia

Dystocia (difficult birth) occurs when the first or second stage of labor is prolonged and assistance is required for delivery. No clear boundaries exist between dystocia and eutocia (normal birth), but guidelines based on progress and duration of the delivery may aid the veterinarian and the producer in deciding when to interfere with the birth process. In the last century, a lot of improvement occurred in the techniques used to deliver and resuscitate calves. Only in the last three decades, however, has research been effectively directed toward the causes and management of dystocia. This may be associated with the more widespread implementation of herd health programs and the use of computers to facilitate data management. The incidence of dystocia varies but generally is more common among first-calf heifers, because they have not yet reached their mature size, and then decreases with age.1 Death due to dystocia or as a result of injuries sustained during delivery is the most common cause of calf loss during the first 96 hours post partum, with most losses occurring during the first 24 hours after delivery.2,3 The subsequent pregnancy rate among dams that suffer dystocia also is reduced.4–6 Although it is not possible to eliminate dystocia, improvements in management of heifers during their development and observation of cows and heifers during the calving season are critical for reducing calf losses.

PARTURITION

During the last weeks of gestation, the dam prepares for delivery of the fetus and the initiation of lactation. Enlargement of the udder may begin in heifers at 5 to 6 months of gestation but may not be obvious in pluriparous cows until the last weeks of pregnancy. The gland may become tightly swollen, and in severe cases, edema may be so extensive in dairy cows as to require induction of parturition or initiation of milking several days before calving. Initial secretions that can be expressed from the mammary gland are viscid and pale yellow to amber in color. As parturition approaches, colostrum is secreted and is white to yellow, turbid, and opaque. The pelvic ligaments relax under the influence of estrogens, relaxin, and the general hormonal milieu that initiates parturition; the gluteal muscles sink, the tailhead becomes more prominent, and the cranial border of the sacrosciatic ligament becomes less tense. A few hours before calving, the vulva becomes edematous, and the cleft elongates. Unfortunately, none of the signs of approaching parturition are specific enough to permit a precise prediction of the exact time of calving; thus, veterinarians have been admonished “to refrain from making too positive or definite a statement regarding the exact time of parturition, as subsequent events will more often than not prove him wrong.”7 Once initiated, delivery of a calf is a continuous process, but for the convenience of discussion, most authors divide labor into three stages or phases.

The first stage of labor signals the beginning of delivery and is characterized by progressive relaxation and dilation of the cervix.8,9 Increased output of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and associated cortisol from the fetal adrenals leads to an increase in the level of the enzyme 17α-hydroxylase in the fetal placenta.10 This in turn reduces placental progesterone production by allowing pregnenolone to be metabolized through to dehydroepiandrosterone. Maternal plasma progesterone concentrations then decrease because pregnenolone is diverted through to estrogen production, and maternal plasma estrogen concentrations subsequently increase. In addition to converting progesterone to estradiol, fetal corticoids also cause the placenta to synthesize prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α). The synthesis of PGF2α helps abolish the progesterone block to myometrial contractility. As both estradiol and prostaglandin become elevated, the myometrium becomes increasingly more motile and begins to display noticeable contractions. Also, PGF2α causes the corpus luteum of pregnancy to regress, facilitating the decline in progesterone.

Clinical signs associated with the first stage of labor most often are observed in primiparous animals; the signs may be minimal or pass unnoticed in older dams. The signs of the first stage of labor generally are those associated with abdominal discomfort and include a variable degree of anorexia, restlessness, shifts of weight from one leg to another, and presence of an arched back with elevated tail. If given the opportunity, most dams will seek solitude away from the remainder of the herd. Some dams may demonstrate mild and intermittent abdominal straining during the late portions of the first stage; thus, the demarcation between the first and the second stage is not as clear in cows as it is in mares. Rupture of the chorioallantois and release of the allantoic fluid (“breaking water”) may be a more accurate attribute by which to mark the end of the first stage of labor. The average duration of the first stage of labor is approximately 6 hours, but considerable variation among animals is observed, and the stage may last up to 24 hours in heifers.11

The fetus is delivered during the second stage of labor, which is characterized by the application of strong abdominal pressure by the dam. Myometrial contractions stimulated by oxytocin force the fetus into and stretch the cervical canal. In particular, the conical shape of the head as the nose enters the cervical canal is important because it progressively dilates the cervix with mechanical pressure. Stretching stimulates the release of more oxytocin from the maternal pituitary gland, which causes further uterine contractions. Oxytocin is thought also to stimulate release of prostaglandins from the endometrium, which further stimulates myometrial contractions.12 This positive feed-forward system makes it difficult to stop labor once it has begun. Forms of dystocia that delay or prevent entry of the head or limbs of the fetus into the cervix, to stimulate the pressure receptors, result in little if any abdominal straining by the cow. A typical example is cranial presentation with full flexion of the hips (true breech presentation).

FACTORS CAUSING DYSTOCIA

Causes of dystocia related to management practices are discussed later in the chapter. From a clinical perspective, the etiology of dystocia is multifaceted and includes defects in the dam or the fetus and management factors, or a combination.13 For purposes of formulating a clinical management plan for an individual animal, it is convenient to divide the causes of dystocia into those of maternal origin and those of fetal origin. It is important to remember, however, that clinical cases may result from multiple underlying disorders and also may require medical treatment to correct concurrent problems, in addition to the more traditional mechanical or surgical treatments.

Maternal Causes of Dystocia

Fetal Causes of Dystocia

Fetal monsters.

A variety of malformations resulting in specific fetal phenotypes and conjoined twins have been described as sporadic causes of dystocia in cattle. Among the fetal monsters more likely to be encountered in cattle are schistosomia reflexus and perosomus elumbus. Schistosomia reflexus, shown in Figure 42-1, is characterized by extreme ventral curvature of the spine, so that the head is positioned near the sacrum. The abdominal and thoracic walls are not closed, and the viscera are exposed. Limbs of the affected fetus frequently are rigid because of ankylosis of the joints.

CASE MANAGEMENT OF DYSTOCIA

Review of History

Progress of the case.

It is important to know how long the animal has been in labor. Cows and heifers should be allowed a reasonable amount of time to spontaneously deliver their calves. It is common for cows to vocalize during straining early in stage two of parturition. This is associated with stretching of the soft tissues of the birth canal.14 Thus, although clinical judgment is necessary, the amount of vocalization during straining may be used as a rough guide to the duration of stage two if the history is not available. If an adequate time for the first or second stage of labor has been exceeded, examination is indicated. Heifers should be allowed a longer time for spontaneous delivery than is required in pluriparous cows. If intervals between observations are excessive (more than 3 hours), the manager will be unable to accurately determine the time of onset of labor, and immediate intervention may be justified. Early obstetric assistance has been shown to improve the subsequent fertility of beef cows.15

Restraint

Accessible facilities and demeanor of the patient often dictate the restraint used for examination and relief of dystocia. Facilities and conditions often are less than optimal. Ideally, however, confinement of the parturient dam should be in a dry, well-bedded enclosure of generous size and with sufficient illumination. Difficult vaginal deliveries often are assisted if the dam can be placed in lateral recumbency; therefore, room to cast and restrain a recumbent animal is ideal. Access to a clean water supply also is desirable. A squeeze chute may be suitable for the initial examination, but the inclination of most cows to become recumbent during traction makes this choice undesirable in all but the simplest of deliveries. Although extraction of the fetus is better performed with the dam in lateral recumbency, the initial examination is more readily performed with the animal standing, because pressure within the abdomen is reduced in this posture. Thus, the patient is most conveniently restrained with a halter, but a stanchion or head bail may be used if caution is exercised to prevent asphyxiation or excessive pressure on the carotid arteries should the animal become recumbent during the examination. During delivery, sufficient space should be available behind the patient to allow manipulation of a fetal extractor or fetatome. A position of lateral recumbency can be achieved with a combination of ropes and sedation. Figure 42-2 shows ropes set on a heifer in preparation for casting in lateral recumbency once diagnostic traction has confirmed that vaginal delivery is possible.

Examination

Rectal Examination

Examination of the reproductive organs by palpation per rectum is indicated in only a few cases of dystocia. The most common indication for rectal palpation is to confirm uterine torsion when stenosis of the cranial vagina is detected during a vaginal examination. Pelvic deformities and exostoses may be more readily detected by palpation per rectum than by vaginal examination. Other indications for palpation per rectum include elicitation of spontaneous movements of the fetus when it is not possible by vaginal examination, confirmation of uterine rupture, and recognition of hemorrhage into the broad ligaments. Although unusual in cattle, firm feces should be removed from the rectum before the application of extractive force.

Vaginal Examination

After determining the disposition of the fetus, the clinician then must determine if it is alive or dead before selecting the appropriate method to complete delivery.24 In cranial presentation, the interdigital claw reflex can be elicited by pinching the web of tissue between the claws. A vigorous fetus responds by withdrawing the foot. A false positive result may occur if the operator mistakes movement caused by the maternal abdominal press for that of the fetus. False negative results can occur in live calves if the head and limbs are wedged in the birth canal. The swallowing reflex is elicited by applying pressure at the base of the tongue, to which a normal calf responds by swallowing or sucking. Slow or exaggerated reactions may be associated with hypoxia or may be agonal. Slight pressure on the eyeball elicits movement of the eyeball or eyelid. The eye reflex is preserved even in severely acidotic calves. The reflexes disappear in a peripheral to central progression as the condition of the fetus deteriorates. That is, the reflexes requiring the longest nerve pathways disappear before those with shorter nerve pathways as acidosis increases. Thus, the interdigital claw reflex disappears first, and the eye reflex is preserved longest. This differential loss of peripheral compared with central reflexes may aid assessment of the physiologic status of the calf.

If the fetal reflexes are ambiguous or absent, the obstetrician should examine the fetal heartbeat or umbilical cord pulse. The heartbeat can be palpated by passing the hand between the fetal forelimbs along the ventral aspect of the neck to the sternum. The fetal heartbeat is then palpable with the examiner’s fingers placed on the left side of the fetal thorax. Palpation of the heartbeat in fetuses presented caudally is difficult. The normal intrauterine heart rate in calf fetuses of 70 to 120 beats per minute increases to 90 to 120 beats per minute during delivery. The heart rate may fall to 40 to 60 beats per minute during uterine contractions. Hypoxia of the dam caused by excitement or exertion can lead to a more severe drop in fetal heart rate. Prolonged or excessive extractive force can cause the fetal heart rate to drop to near zero. As a calf becomes acidotic as a result of delayed delivery, the heart rate first increases to 140 beats per minute and then falls and becomes irregular as its condition deteriorates.

For inexperienced obstetricians, effective guidelines have been formulated to assist in the decision-making process for determining if vaginal delivery is possible.14 The basis for these guidelines sometimes is referred to as “diagnostic traction.” When the fetus is in cranial presentation, dorsosacral position, and normal posture, if one person can pull the fetlocks 10 to 15 cm beyond the vulva (approximately one hand’s breadth), the points of the shoulders will pass the maternal iliac shafts and the calf can be delivered vaginally if correct delivery techniques are used. When the fetus is in caudal presentation, dorsosacral position, and normal posture, if one person pulling on each leg can make the hocks appear at the vulva, the greater trochanters will pass the iliac shafts and the calf can be delivered vaginally. As experience is gained, other factors can be included in the decision-making process. For example, the chance for successful delivery by traction is increased in the following circumstances14:

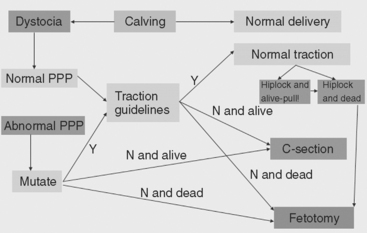

On completion of the examination and assessment of the condition of the fetus, the dam, and the birth canal, the clinician must then formulate a plan for resolution of the dystocia. The available options in cattle are mutation of abnormal presentation, position, or posture; forced extraction; fetotomy; pelvic symphysiotomy; and cesarean section.16 Euthanasia may be indicated in situations in which the value of the animal is limited and the prognosis poor. When formulating a plan to deliver the fetus, the clinician must consider the value of the dam and the potential value of her offspring, the cost of the procedure and aftercare, and the prognosis for the life of the dam and the fetus and for the dam’s future reproductive performance. Often, the facilities and assistance available, as well as the personal preferences of the animal’s owner and the clinician, will influence the decision. Figure 42-3 is a flow diagram of the decision-making process that can be used by the clinician in clinical management of dystocia.

MUTATION OF ABNORMAL PRESENTATION, POSITION, AND POSTURE

Definitions

Version

Version is defined as turning the fetus on its transverse axis into cranial or caudal presentation. Transverse presentation fortunately is rare in cattle but must be converted to longitudinal presentation before delivery is attempted. Extractive force is applied to the portion of the fetus closest to the maternal pelvis while the opposite pole of the fetus is repelled. Version usually is limited to 90 degrees, and attempts to convert caudal presentation to cranial presentation are not likely to be successful and will commonly result in uterine tears.

Correction of Displacement of the Extremities

Displacements of the Hindlimbs

To correct hock flexion posture, the limb is grasped at the metatarsus and repelled cranially and laterally until sufficient space is available to draw the hoof in a caudal and medial direction into the pelvic canal. The operator should cover the hoof with one hand to protect the uterine wall as it is rotated medially. In some cases, application of a snare distal to the fetlock joint can facilitate correction. The cord is placed between the digits of the affected hoof, and traction is applied. The operator then applies opposing forces by repelling the hock while simultaneously applying traction to the snare. This action results in flexion of the fetlock and pastern joints while the hoof is drawn toward the pelvic brim.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree