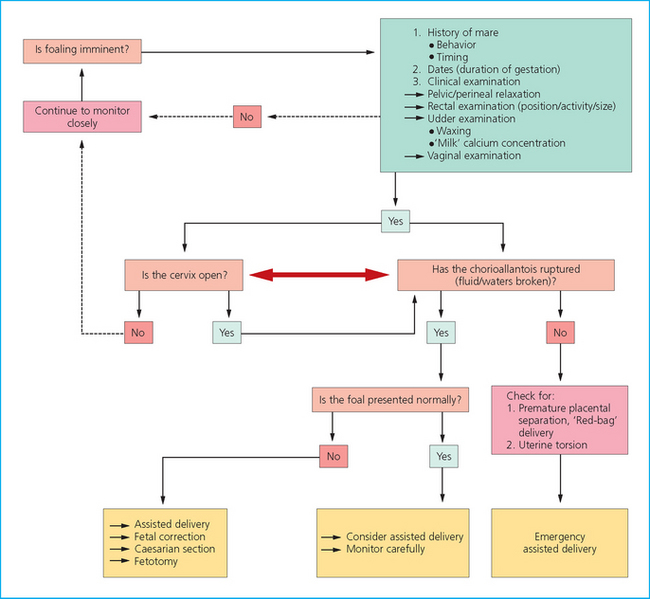

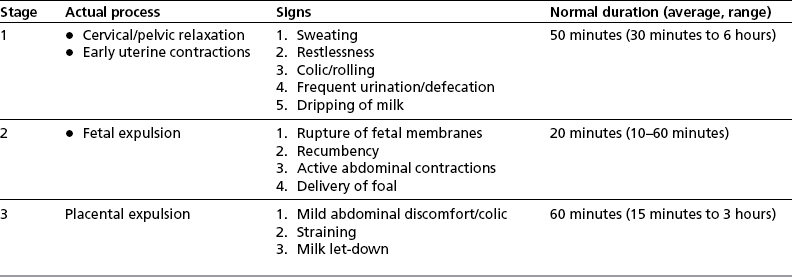

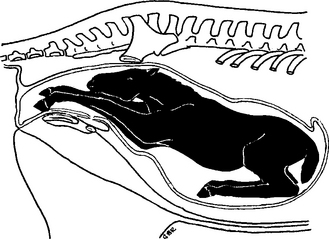

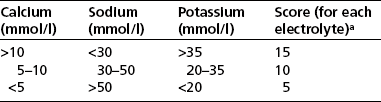

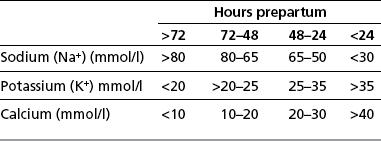

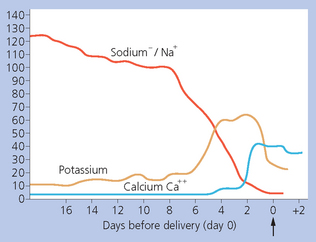

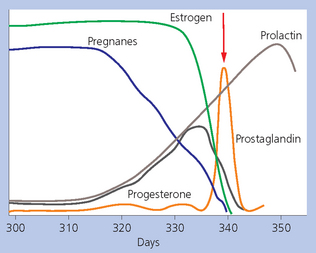

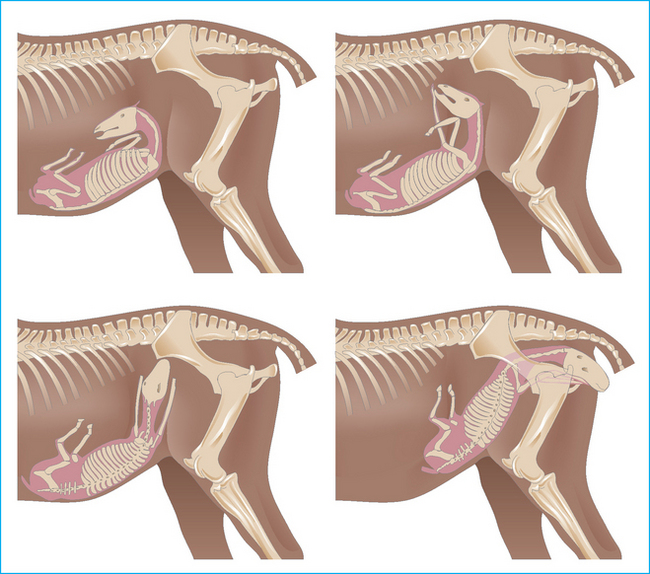

Chapter 8 The duration of pregnancy in the mare is normally said to be between 335 and 342 days.1 However, there is a naturally wide range of normal gestational length (320–400 days).2,3 Mares that foal in the early spring (February and March in the northern hemisphere breeding season) tend to have longer gestation lengths than those foaling in late spring and summer. It is believed that there is a period of embryonic diapause (a period of time during which the developing embryo stops growing and simply remains the same size), which may vary in length from a few days to weeks, depending on the individual mare. This may in part account for the natural, well-recognized variability in gestation length in mares. Signs of impending parturition include: • Relaxation of the pelvic ligaments and perineum. • Mammary gland development (Fig. 8.1). • Waxing of the teats (see Fig. 7.37). A wax-like secretion may be seen on the teats (see Fig. 7.37). Wax is part of the initial tenacious colostrum fluid produced by the mammary gland. Waxing typically occurs up to 72 hours prior to foaling, although in some mares it may occur up to 2 weeks prior to parturition. There may be only a drop or two of wax or up to several inches of secretions. Some mares may leak colostrum prior to foaling. If the mare is streaming milk for an extended period of time (hours at a time, or several times a day), she should be milked out and the colostrum frozen and saved for the foal, rather than taking the chance that all the colostrum might be lost prior to foaling. Concentrations of electrolytes in the milk will change in the days before foaling (Fig. 8.2).5,6 These are useful indicators of fetal maturity and are therefore helpful to some extent in determining foaling dates and in assessing the appropriateness of induced parturition (see p. 279). Milk electrolyte levels have been shown to be potential predictors of foaling (Table 8.1), or at least the times when the mare is unlikely to foal. However, they should not necessarily be relied upon to provide a definite indication of impending parturition. Table 8.1 Alterations in the electrolyte content of mammary secretions in the immediate prepartum period Fig. 8.2 The approximate changes that occur in electrolyte concentrations in mammary secretions in the normal pregnant mare in the days leading up to delivery (day 0, arrow). • Milk electrolytes, and calcium in particular, can be measured colorimetrically or by flame photometer in an aqueous aliquot of the centrifuged specimen of mammary secretion. • Commercial kits are available to measure calcium levels using a rapid strip dry chemistry test (i.e. water hardness testing kits).7 These tests are convenient and helpful but were designed to detect calcium concentrations in water (Sofchek, Environmental Test Systems, Elkhart, IN, USA; Titrets Calcium Hardness Test Kit, CHEMetrics Inc., Calverton, VA, USA). The tests need to be calibrated as they are usually working at the limits of their range. • Kits designed specifically for horses are available commercially (Predict-a-Foal Mare Foaling Predictor Kit, Animal Healthcare Products, Vernon, CA, USA). • The specific equine test strip has been shown to be easier to interpret but had wider variations than the tests using water hardness values.8 • An increase in calcium to greater than 10 mmol/l, a decrease in sodium to less than 35 mmol/ml and an increase in potassium to greater than 80 mmol/ml are all indicators of fetal maturity and impending parturition. Late-term pregnancy in the mare has a unique hormonal environment (Fig. 8.3).9–11 Fig. 8.3 The endocrinology of late pregnancy. Estrogen production begins to fall just before parturition (arrow). Pregnanes slowly reduce over the last 4 weeks of pregnancy and decrease precipitously immediately at parturition. Progesterone gradually increases during the last month of gestation and then falls rapidly after foaling. Prostaglandin is significantly increased during stage 1 of labor with peak concentrations achieved during stage 2. Oxytocin peaks during stage 2 of labor immediately following the prostaglandin surge. Prolactin gradually increases over the last month of pregnancy, peaks at around 30–60 days after parturition and then tapers off over the next 2–4 months. • There are high levels of fetally derived estrogen. The levels of estrogens produced by the fetoplacental unit and fetus remain relatively stable until parturition. • Progesterone rises during the last few weeks of pregnancy with a peak about 5 days before foaling, whereas pregnane levels are decreasing (although they are still found at high levels).12 • Both progesterone and the 5α-pregnanes decrease precipitously following parturition and are at baseline levels within 24 hours of foaling. • The ratio of the declining progesterone concentration to the stable estrogen provides the stimulus for the formation of oxytocin receptors and instigates changes in the muscular ability of the uterus to enable it to contract forcibly. Relaxin is a hormone produced by the placenta13 that stimulates relaxation of the pelvic ligaments in the birth canal and cervix. Concentrations of relaxin reach their peak during stage 2 of labor (fetal expulsion). Prostaglandin F metabolites slowly begin to increase during the last third of pregnancy14 and increase more significantly during the last 2 weeks. Prostaglandin, which is derived from the fetoplacental unit, reaches peak concentrations at the end of stage 1 of labor; this is partly responsible for cervical relaxation. Concentrations increase again at the onset of stage 2 of labor; this is partly responsible for the onset of coordinated uterine contractions. • Disturbances in the mare’s environment may result in her delaying delivery until she feels comfortable with her surroundings. • In this situation, the milk calcium level may be greater than 10 mmol/l and foaling may not occur within 48 hours as predicted by the kits (see p. 270). The mare should be checked twice daily for signs of impending labor and possibly even more frequently as the signs of impending parturition develop. When the mare is very close to foaling she should be monitored frequently for signs of labor. Hourly or bi-hourly visits to the foaling stall/area should be made. For the most part interference should be minimized unless the mare is clearly in trouble. In order to minimize the extent of interference, supervision should be provided through some type of monitoring system (visual, video, alarm). • Video monitoring systems can be set up in the mare stall, with remote TV monitors to evaluate foaling activity. These systems are unobtrusive, but are expensive and they require personnel to monitor the TV system. • Belt/girth alarm systems, which are activated when abdominal contractions begin, can be strapped to the mare’s abdomen. They can be attached to a pager or phone system. False alarms may occur with these systems when the mare grunts or groans when in lateral recumbency. • Transducers (or magnets) sutured to the vulvar lips are activated when the amniotic sac parts the vulvar lips. However, some mares are irritated by the transducers and will rub against a wall and tear the transducer out. These systems can be attached to a pager or phone system. • A system utilizing a spirit level attached to the mare’s head collar which is activated when the mare lies in lateral recumbency is also available. This system relies upon the movement of the bubble to either end of the spirit level. There is plenty of scope for false alarms with this system when the mare simply lies down to rest. • This discomfort may be recognized as colic by the owner. It is typically responsive to hand-walking, time, or administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. As parturition approaches the mare will usually show a decrease in appetite.15 She may also try to separate herself from the rest of the herd if she is in a group. If the mare has been previously subjected to a Caslick’s operation (Fig. 8.4) she should be examined in stocks, if possible twitched rather than tranquilized. Fig. 8.4 Mares that have been subjected to a Caslick’s vulvoplasty operation should be restrained and the sutures removed if still present. A surgical episiotomy usually prevents uncontrolled and unpredictable perineal laceration and delays in delivery. • After local anesthetic has been infiltrated along the previous incision line, the previously closed vulvar lips are sectioned to return the vulvar opening to its natural dimensions. As far as possible foaling should not take place into a dirty, wet or muddy environment; stable facilities should be clean and free of any possible infectious agents, and foaling should occur apart from other foaling mares in particular. The management and hygiene involved in the preparation of the foaling box is described in Chapter 1. • If the mare is to foal inside, a 6 × 6–7-meter loosebox is an adequate area. The mare should be carefully monitored to ensure that she does not foal into a corner. • If the mare is to foal outside, there should be some shelter for the foal after birth. A clean, dry, grass pasture is ideal. The flow chart presented in Fig. 8.5 provides a useful protocol for the decisions that need to be made at parturition. Labor is classically divided into three stages (see Table 8.2). This stage involves contraction of the uterus and cervical relaxation. The average duration is about 1 hour, although the range may be from 30 minutes to 6 hours, or longer in some cases. The mare has some ability to control the duration of stage 1 labor; if she is unduly upset or disturbed, she can postpone stage 2 for hours or even days. The fetus takes an active role in its own positioning during stage 1, often becoming noticeably active. Fetal movements can sometimes be seen in the flank as the foal actively rotates from a dorsopubic (upside-down) position (Fig. 8.6) to a dorsosacral (right-side up) position. Rolling by the mare assists in this process of fetal positioning which is required for a normal delivery. Preventing the mare from rolling is not recommended but it is important to distinguish this normal rolling behavior from that associated with severe abdominal pain. Fig. 8.6 Rotation of the foal in stage 1 of labor. The foal remains in a dorsopubic or dorso-ilial position until stage 1. Rotation of the fetus is an active process involving the mare (through lying down, rolling and rising) and the foal (through rolling and turning). • Rolling, pawing, kicking at the abdomen, looking back at the abdomen (signs commonly attributed to abdominal pain/colic). • Anorexia. The appetite of many late-term mares is normally reduced. This may have serious implications for overweight ponies liable to the hyperlipemia syndromes. • Sweating may be noted on neck and flanks. • Frequent urination and defecation (possibly in an attempt to clear the pelvic canal for the impending delivery). • Frequent laying down and rising (this can also be mistaken for colic). Stage 1 ends with the rupture of the chorioallantois and the sudden release of a quantity of tan-red colored fluid. This is the ‘breaking of the water’ or ‘water breaking’ (Fig. 8.7). Fig. 8.8 Stage 2 of parturition begins with the mare showing increasing discomfort and ‘colic’ signs. Fig. 8.9 Signs of stage 2 labor. Rupture of the chorioallantois is followed by the appearance of the gray amnion (A). The foal’s legs (B) will appear next (one slightly behind the other). Increasing straining delivers the head (C) and the foal’s delivery is rapidly completed (D). The mare remains calm and recumbent during the final delivery of the hind legs (E). The foal makes energetic attempts to move towards the head of the mare (F); during this the cord will usually break (G). Once the cord has broken the mare will usually rise and lick/sniff the foal (H). • During this stage the mare will usually lie down and have active abdominal contractions. • While some mares will foal standing up, most adopt lateral recumbency for the delivery. • When the fetus enters the birth canal it stretches the surrounding tissues, stimulating surges in both prostaglandin and oxytocin. These in turn cause uterine and abdominal contractions to occur (known as Ferguson’s reflex). • The abdominal contractions are very powerful, each lasting for between 15 seconds and 1 minute. • There will usually be several contractions in succession and then a period of rest (lasting 2–3 minutes) before the next set of contractions. • The mare may reposition several times during rest periods and may rise to her feet before lying down again. • Shortly after the waters break, the amnion, which directly surrounds the fetus, is usually presented. • As contractions continue, the fetal legs will be seen at the vulvar lips. • Once the fetus enters the birth canal, contractions tend to occur more frequently until the foal’s hips are delivered through the birth canal. Commonly, the mare may rest for several minutes at this time before finally expelling the foal. • Stage 2 ends with the expulsion of the foal and usually lasts 15–60 minutes. Interference in the foaling process is considered appropriate if: • There is no evidence of strong contractions and/or no progression in the delivery process 15 minutes after the rupture of the chorioallantois) (water breaking). • One foot and the head, or two feet and no head, or if only the head are presented at the vulva. • If the red, velvety surface of the chorionic membrane appears at the vulva instead of the tough, semitransparent, gray amnion before the foal is delivered. This is the so-called ‘red bag’ delivery. THIS IS A TRUE EMERGENCY SITUATION (see p. 299). • If rectovaginal perforation occurs. This can be recognized by the foal’s leg appearing through the anus of the mare. THIS IS A TRUE EMERGENCY SITUATION (see p. 286). The umbilical cord will separate on its own either as the foal moves about in trying to rise or when the mare stands up. There is some difference of opinion about what to do with regard to the umbilical cord.16 Transfer of up to 1 liter of blood from the placenta back to the foal will occur until the cord breaks. This blood will pass both from the mare to the foal and from the foal to the mare. It is believed by some that this transfer of blood to the foal is important for its immediate well-being during the first few days of life. However, no significant differences in blood volume have been demonstrated between foals whose umbilical cords were allowed to remain patent for a quarter to half an hour after birth and those whose cords were severed and ligated immediately after delivery. Nevertheless, it is probably best if the umbilical cord is allowed to break naturally. If this occurs immediately after birth, it is not a reason for serious concern. If the mare and foal are both resting quietly, the cord should be allowed to remain intact until the actions of either the mare or the foal result in its spontaneous rupture. • Strong myometrial contractions may induce abdominal pain/discomfort (colic). The mare may lie down and get up repeatedly. The placenta should be allowed to hang from the vulvar lips (see Fig. 8.11); however, if it is dragging on the ground or hitting the hocks it should be tied up, so the mare does not tear it off or kick at it and so injure the foal. Fig. 8.11 Third-stage labor may be delayed. The placenta should not be forcibly removed, but it can be tied up to minimize the inconvenience. The placenta can be a source of serious infection for the foal. Once the placenta has been delivered it should be placed in a bag and kept cool or refrigerated until it can be examined by a veterinarian (see p. 328). The veterinarian should examine every placenta in order to: Uterine involution occurs quite rapidly in the mare. • In the event that a veterinarian cannot examine the mare immediately, advice on the possible use of 2-hourly intramuscular injections of 40 IU of oxytocin can be considered. • There are important unwanted effects from this treatment so consultation with the veterinarian must be made before any treatment is given. In most countries the drug is only available on prescription. Management of retained placenta will be discussed later in this chapter. Care of the foal immediately after birth is critical for its well-being. The protocol for this is described on p. 365. A careful diary of events should be recorded. The mare should be allowed some quiet time to bond with the foal immediately after delivery. During this time discreet observation can be maintained to ensure that no problems develop as a result of a nervous, apprehensive or aggressive mare, but the mare should not be disturbed until it is clear that there is a strong mutual bonding between the mare and foal. This is especially important for maiden mares or nervous mothers to ensure that abandonment will not occur. In the event that there are behavioral problems, the foal can be separated from the mare by a divider or the mare can be held by a familiar and experienced handler to allow the foal to approach and nurse. In some cases, the mare may need to be sedated before it will allow nursing until the pressure on the full udder decreases and the mare becomes accustomed to the feel of the nursing foal. On rare occasions, rejection of the foal may occur. A nurse mare may be required or the foal may need to be to raised as an orphan. The latter is to be avoided at almost any cost. • Premature placental separation; this is common with induced parturition. • Failure of passive transfer (p. 375). • Fetal or maternal compromise and death. • Neonatal maladjustment syndrome. This is quite common in foals born by induction even when at full term, and immediate (and often long-term) care is often required for their survival. There are considerable advantages in an induced parturition but also significant dangers. The procedure should not be undertaken lightly.9–11 Induction performed by the attending veterinarian provides continuous professional care and monitoring for the mare and the foal. Problems such as premature placental separation and fetal malposition/dystocia can quickly be recognized and dealt with without delay. Furthermore, careful and full preparations can be made in advance and the tendency for mares to foal in the early hours of the morning can be negated. The indications for induced delivery include: • A classification as a high-risk foaling as a result of mare or foal classification. • History of difficult deliveries or previous abnormal or problematical foals; thus foaling or situations in which the life of the mare or foal is likely to be in jeopardy can be supervised. • Habitual or anticipated premature placental separation (‘red bag’ delivery). • History of primary uterine inertia resulting in delayed delivery. • Inability to strain effectively (abdominal muscle, diaphragmatic or tracheal defects). • Physical deformity of the maternal pelvis, or with a history of previous pelvic injury including old fractures, such that attended labor is critical, impending rupture of the prepubic tendon, or uncontrolled and recurring prefoaling colic. The decision must include the possibility of cesarean section rather than induction of parturition. • Detectable fetal distress or other life-threatening injury or disease in the foal or the mare. • There should be colostrum in the udder. • Gestational age must be between 330 and 350 days. Although the actual gestational age is important, the previous history of the individual mare might suggest that a delay or an earlier induction might be indicated. Thus it is probably not wise to assume normality in a primiparous mare and an assumption based upon the ‘normal’ gestational duration of the horse is most unwise. Optimal survival is achieved by induction within 10 days of normal delivery date for that pregnancy. • Pelvic relaxation should be present. The cervix should be relaxing/dilating (as detected by manual examination or vaginoscopy). • The fetus should be in a normal presentation, position, and posture. • Mammary secretion analysis is consistent with readiness for birth. The milk calcium level should be >10 mmol/l (>200 ppm).5,21 A system that provides a score derived from calcium, sodium, and potassium can be used if each of these can be measured accurately (see Table 8.3).22 This usually requires a laboratory that is equipped to perform specialized testing procedures. It is often worth measuring the IgG concentration if the milk calcium has risen sufficiently to permit induction to determine if passive transfer will be normal following delivery. This measurement should be performed again after the foal has been delivered. Assessment of fetal maturity by evaluating mammary secretion concentrations of calcium, sodium, and potassium is described on p. 270.

PARTURITION

PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES THAT OCCUR BEFORE FOALING4

Mammary development and secretions

ENDOCRINOLOGY OF PARTURITION

PREPARATION FOR FOALING

STAGES AND SIGNS OF LABOR

Stage 1

Signs of stage 1

Stage 2

Signs of stage 2 (Figs 8.8, 8.9)

The amnion is a bluish-white sac that commonly looks like a balloon at the vulvar lips.

The amnion is a bluish-white sac that commonly looks like a balloon at the vulvar lips.

It is usually wise to ensure that the amnion is removed from the foal’s muzzle as soon as the foal’s chest clears the pelvic canal so that it can breathe.

It is usually wise to ensure that the amnion is removed from the foal’s muzzle as soon as the foal’s chest clears the pelvic canal so that it can breathe.

Under natural conditions, opposing movements of the foal’s head and legs rupture the amnion, resulting in a smaller rush of yellowish allantoic fluid.

Under natural conditions, opposing movements of the foal’s head and legs rupture the amnion, resulting in a smaller rush of yellowish allantoic fluid.

Normally, the two front feet are presented first, with one hoof slightly ahead of the other and the head resting on the foal’s knees (Fig. 8.10).

Normally, the two front feet are presented first, with one hoof slightly ahead of the other and the head resting on the foal’s knees (Fig. 8.10).

Stage 3

PLACENTAL RETENTION

POSTNATAL CARE

INDUCTION OF PARTURITION

Indications for induced delivery

Criteria for decision

Methods of induction