4 Parasitology

Heartworm is becoming more common everywhere in the United States. Very few dogs never go outside, and even those that live exclusively inside may be exposed to mosquitoes inside buildings. Heartworm is difficult to treat, and prevention is much preferred. Although I do not like to treat pregnant bitches with anything that is not absolutely necessary, I do recommend heartworm preventive for any bitch that lives in a part of the country with a significant mosquito population. Most heartworm preventives have been proven safe to use in pregnant dogs.

Some parasites are visible with the naked eye or are easily retrieved from the skin or anal area of affected animals for identification with the light microscope. Other parasites complete their life cycle within the animal or are not visible with the naked eye, requiring other diagnostic tests. Be aware that none of these diagnostic tests is 100% accurate for diagnosis of parasitism.

I. INTERNAL PARASITES

A. WORMS

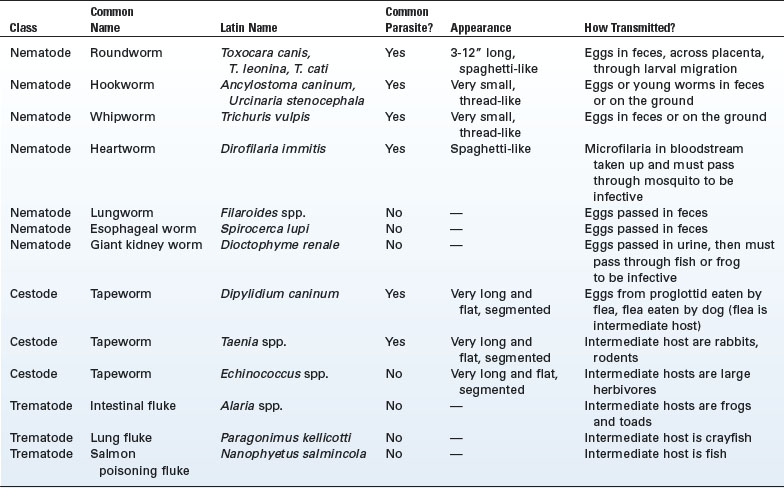

The three types of worms (helminths) are roundworms (nematodes), flatworms (tapeworms or cestodes), and flukes (trematodes). Nematodes are elongate and cylindrical with tapered ends and are unsegmented. A given nematode is either male or female. Cestodes are the tapeworms. These are flat worms and are segmented. Cestodes are hermaphrodites, carrying both male and female reproductive organs. Trematodes are flattened worms with an arrow-shaped head. Parasites from all three classes have been described in dogs (Table 4-1). Only those species that are of great concern to pet owners and kennel managers are described in detail here.

1. Roundworms

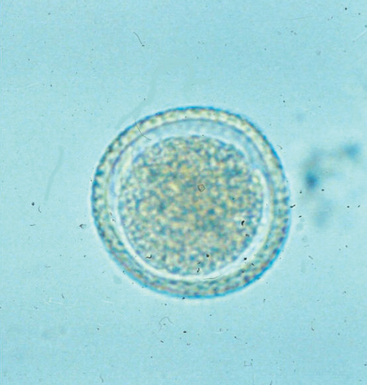

Adult worms are spaghetti-like in appearance, ranging in length from 3 to 12 inches (4 to 18 cm). Roundworm eggs are slightly ovoid with a thick, slightly pitted shell containing a round embryo (Figure 4-1).

Anthelmintics used to treat roundworms include piperazine, pyrantel pamoate, and fenbendazole (see Chapter 2). Environmental contamination is possible; the eggs can overwinter and are resistant to chemicals. Control of roundworms in a facility includes (1) treatment of all bitches late in gestation, (2) treatment of all pups beginning at 2 weeks of age, (3) regular fecal flotation testing of all dogs in the facility, and (4) excellent sanitation.

Roundworm eggs may persist in the environment, especially in soil, for years. Measures that may be used to attempt decontamination of the environment include the following:

2. Hookworms

Adult hookworms live in the small intestine, where they attach to the wall and ingest large volumes of blood. Female hookworms lay thousands of eggs daily. The eggs are passed in the feces and hatch outdoors with development of the infective larval stage within 4 to 8 days. The larvae penetrate the skin and enter the circulatory system and lungs from where they are coughed up and swallowed, allowing them to colonize the intestinal tract. Passage from the pregnant bitch to pups through the placenta is uncommon; however, larvae form cysts in female dogs that remain latent until the bitch is stressed with pregnancy. Reactivated larvae will migrate through the bitch’s body and may migrate into the mammary tissue; passage of hookworm larvae to pups from the nursing bitch through the milk is not uncommon.

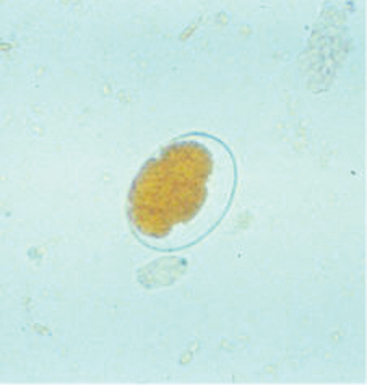

Adult hookworms are tubular, up to 1 inch (2.8 cm) long, and are red. The anterior (“mouth”) end is bent, creating the hook for which they are named. Hookworm eggs are thin-shelled and oval and contain two to eight round cells (Figure 4-2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree