17 OVERVIEW AND LYMPHOMA/LYMPHOSARCOMA

2 Is there a difference between lymphoma and lymphosarcoma?

A common contraction of the term “malignant lymphoma,” lymphoma is the conventional human nomenclature for lymphoid neoplasms arising as solid tissue masses in organs outside the bone marrow.1 The term “lymphoma” is a misnomer in that the suffix oma typically denotes a benign neoplasm. However, a benign form of this lymphoid neoplasm does not occur in either human or veterinary medicine. For this reason, the “malignant” portion of malignant lymphoma is understood, and the abbreviated lymphoma is often used alone. Lymphosarcoma is a term used in veterinary literature to denote malignant lymphoma. Therefore the terms lymphoma, malignant lymphoma, and lymphosarcoma are synonymous. Because of its acceptance within human literature, the term lymphoma is be used throughout this text.

3 What is the incidence rate of lymphoma in different veterinary species?

Lymphoma is by far the most common hematopoietic tumor in the dog, accounting for 80% to 90% of these tumors2 and approximately 5% to 7% (up to 24% reported)3 of all canine neoplasms. Incidence rate is estimated to be 13 to 24 per 100,000 dogs at risk annually.3

As in the dog, lymphoma is generally thought to be the most common of the feline hematopoietic tumors, accounting for 50% to 90% of these tumors in the cat.2 Some authors question the current validity of these statistics, however, because they were generated in studies conducted before widespread availability and use of feline leukemia virus (FeLV) vaccination and testing. Indeed, the change in incidence of FeLV infection has greatly changed both the age and the site distribution of lymphoma in cats. More recent surveys indicate a 25% incidence of FeLV infection in cats with lymphoma, in contrast to 60% to 70% reported in earlier studies.4

Although occurring much less frequently in the horse than in either dogs or cats, lymphoma is still among the most common malignant neoplasms of horses, accounting for 1% to 3% of equine malignancies.5 Lymphoma was the fifth most common malignancy diagnosed in equine patients in a University of California survey.6

In the cow the occurrence of lymphoma varies with age and husbandry practices. Although the most frequent malignant neoplasm of dairy cattle, lymphoma is second in frequency to ocular squamous cell carcinoma if production type is not considered.6 Prevalence has been reported at 18 per 100,000 slaughtered cattle in the United States, although incidence rates vary dramatically in age-stratified studies.6 Lymphoma is reported to occur infrequently in the absence of bovine leukemia virus (BLV) infection.7

4 Does age play a role in the incidence of lymphoma?

In general, occurrence of lymphoma increases with increasing patient age. Middle-aged to older animals are most often affected. In dogs the average age at diagnosis is 6 to 9 years.3 Lymphoma may develop in younger animals, however, and has been reported to occur in dogs as young as 4 months and in the bovine6 and equine5 fetus. Unfortunately, lymphoma in younger animals is often a high-grade, aggressive type.4

A bimodal age distribution is seen in the development of lymphoma in cats and in cattle.2,6 This is largely attributable to the incidence of a retroviral etiology in these species. In cats, lymphoma incidence increases at 2 to 3 years age, then again at 6 to 12 years.6 These peaks represent very different manifestations of lymphoma. Lymphoma occurring in younger cats is more often thymic in origin, is more frequently associated with FeLV infection, and is more often the T cell phenotype.8 In contrast, lymphoma in older cats is more frequently alimentary in origin, is of B cell phenotype, and is less often associated with FeLV infection.

5 Are breed predispositions seen with lymphoma?

In the dog a number of breed predispositions in the development of lymphoma have been documented. Scottish terriers, boxers, basset hounds, bulldogs, Labrador retrievers, bullmastiffs, Airedale terriers, and Saint Bernards are all reported to be overrepresented.2,3,6 In contrast, other breeds may be at decreased risk for development of lymphoma. Dachshunds and Pomeranians have been reported as underrepresented. A genetic predisposition has been suggested in the dog as a result of familial incidence of lymphoma in Rottweilers, otter hounds, and bullmastiffs.3,6

Cats also exhibit breed predispositions. The oriental breeds, in particular the Siamese, have been reported to be overrepresented in development of lymphoma.6,8

In cattle, breed predispositions are not actually seen, but dairy breeds do exhibit an increased incidence of lymphoma relative to that seen in beef cattle.6 This is thought to be attributable the differences in average age and management practices.

6 What is the importance of classifying lymphoma, and which features are used in classification?

A variety of criteria may be useful to subclassify lymphomas further, including anatomic location, cell morphology, histologic tumor appearance, and cell immunophenotype. Distinct variations in tumor behavior are seen among the various anatomic sites of lymphoma. Age is also important, particularly in the feline and bovine, in which anatomic site, age, and viral infection are closely linked. Anatomic features such as mitotic index (reflecting tumor cell proliferation rate) may predict response to therapy. Lymphomas may be subcategorized into low grade (0-1 mitotic figures per high-power field [HPF]), intermediate grade (2-4 mitotic figures/HPF), and high grade (>5 mitotic figures/HPF).6 Disease progression and response to therapy both increase with increasing tumor grade.

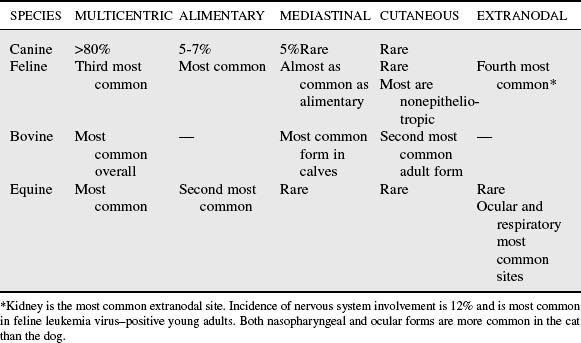

7 Discuss the anatomic categorization of lymphoma in veterinary species.

Anatomic classification of lymphoma is common mode of tumor categorization in veterinary medicine. Anatomic forms include mediastinal (thymic), alimentary (gastrointestinal), cutaneous (and subcutaneous), multicentric (generalized), and extranodal (solitary or regional) forms, based on site of primary tumor involvement. The incidence of various anatomic forms varies among species (Table 17-1).3,9

Cat

Mediastinal and alimentary forms are most common in the cat. The alimentary type occurs most often in older, FeLV-negative cats and may be diffuse or may occur as solitary lesions. Solitary alimentary lymphomas occur more often in the cat than the dog.3 B lymphocyte phenotype is most common. Among alimentary lymphomas in the cat, 50% to 80% arise within small intestine, with the remaining 25% in the stomach, ileocecocolic junction, and colon (in decreasing order of frequency). Lymphoplasmacytic enteritis may be a predisposing factor and may progress to alimentary lymphoma.4 The mediastinal form occurs in younger, FeLV-positive cats and involves the thymus and the mediastinal and sternal lymph nodes.4,6 T lymphocyte phenotype is most common in this form. Pleural effusion frequently occurs and may occasionally contain neoplastic cells. Hypercalcemia, a frequent manifestation of thymic lymphoma in dogs, is uncommon in cats.4 Prevalent sites of extranodal lymphoma in cats include the kidneys, eyes and retrobulbar space, central nervous system (CNS), nasal cavity, and skin. Renal involvement may also be seen, with extension of lymphoma arising in the alimentary tract. One quarter to one half of cats with renal lymphoma are FeLV positive.8 CNS extension occurs in 40% to 50% of feline renal lymphoma cases. Primary CNS lymphoma is primarily extradural and associated with the spinal canal. A strong association with FeLV infection is seen; 85% to 90% of cats with primary CNS lymphoma are infected. Lymphoma is second only to meningioma in frequency among feline CNS tumors. Extranodal primary nasal lymphoma is usually localized, although systemic involvement occasionally occurs. It is usually of B lymphocyte phenotype, and affected cats are most often FeLV negative. Primary ocular lymphoma is more common in cats than in dogs. Cutaneous lymphoma, either primary or less frequently secondary to metastasis of multicentric lymphoma, is seen most often in older, FeLV-negative cats and may be focal or diffuse. Two forms are seen: epitheliotropic, most often of T lymphocyte phenotype, and nonepitheliotropic, most often of B lymphocyte phenotype.4

Dog

Multicentric lymphoma, accounting for 80% to 85% of canine lymphoma cases, is the most common anatomic form seen in the dog. Alimentary lymphoma is the second most frequent and accounts for 5% to 7% of canine cases.3,6 As in the cat, alimentary lymphoma may occur either multifocally or diffusely throughout the submucosa and lamina propria of the small intestine in the dog. Lymphocytic plasmacytic inflammation may be associated with alimentary lymphoma, which some consider a potentially prelymphomatous change. Thymic lymphoma is seen in 5% of dogs and is most often of T lymphocyte phenotype.3 Cutaneous lymphoma in the dog may be solitary or generalized, and epitheliotropic and nonepitheliotropic forms are described. As in the cat, epitheliotropic lymphoma in the dog is most often of T lymphocyte phenotype.6 This form may involve oral mucosa and extracutaneous sites as well.3 A rare form of cutaneous T cell lymphoma, Sézary syndrome, has been reported in the dog, cat, and horse and is associated with circulating atypical lymphoid cells that have convoluted nuclei.3,4,10 Nonepitheliotropic cutaneous lymphoma in the dog may be of either B or T lymphocyte phenotype. The B lymphocyte type characteristically spares the epidermis and is concentrated in the middle to deep dermis.3

Horse and Cattle

In the horse, as in the dog, the multicentric form is most prevalent. Alimentary is the second most common, followed by thymic, extranodal cutaneous, ocular, and respiratory forms, which are rarely reported.6,8

As in the cat, prevalence of the various anatomic forms of lymphoma in cattle varies with age and viral status. In younger, BLV-uninfected cattle, thymic lymphoma is most often seen. In older cattle, BLV lymphomagenesis is associated with development of multicentric lymphoma. Because affected animals in either group are often presented late in the course of disease, lesions are frequently widespread and multicentric. Cutaneous lymphoma is a distinct entity in adult cattle that manifests as waxing and waning, raised, hairless, sometimes ulcerated lesions concentrated over the neck, shoulders, and perineum. Development of multicentric lymphoma eventually occurs.6

8 What is immunophenotype, and what is the role of immunophenotyping in characterizing lymphoma?

In the dog, lymphoma phenotype is linked with tumor behavior and prognosis. For example, incidence of hypercalcemia in canine lymphoma patients overall is approximately 10%. A much greater incidence of hypercalcemia (40%-50%) is seen in dogs with thymic T cell lymphoma,8,6 illustrating a difference in behavior among this subset of neoplastic lymphocytes. Compared with B cell lymphomas, T cell tumors exhibit a poorer remission rate with chemotherapy, a shorter disease-free interval, and reduced survival. Among B cell tumors, those exhibiting decreased B5 surface antigens are characterized by shorter remission and survival times.3

The majority of lymphoma in the cat, the dog, the horse, and in adult cattle is of B cell phenotype.2,6 B cell tumors may be infiltrated with large numbers of nonneoplastic T lymphocytes, an entity commonly referred to as “T cell–rich B cell lymphomas.” This variant has been reported most often in the horse, but also in the cat, dog, and pig.11 Anatomic distribution and phenotype are often associated. T lymphocyte phenotype predominates in mediastinal forms in the dog, cat, and calf6 and in the CNS form in the cat.4

9 Which human lymphoma classification schemes have been used in veterinary medicine?

The Rappaport system is the oldest classification followed in veterinary medicine. It was accepted as a classification for human non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHLs) in 1956.12 This system considers pattern of growth (follicular or diffuse) and cytologic features of the neoplastic lymphoid cells (well differentiated, poorly differentiated, or “histiocytic”) in classification of tumor type. In contrast to human medicine, veterinary follicular lymphomas are uncommon. Also, advances in biotechnology and cell identification have all but eliminated use of the confusing term “histiocytic” to describe lymphomas. Ultimately, such a classification system based on morphology alone has been found to be an inadequate predictor of biologic behavior and prognosis of lymphoma in animals.

The Kiel system added immunophenotype to cell morphology in classifying lymphoma, resulting in improved prognostic value compared with the Rappaport system.2

The NCI Working Formulation represented an attempt to unify the existing human lymphoma classification schemes by developing a consensus report among the leading authors on lymphoma classification during the late 1970s,13 in the hope of permitting more meaningful comparison of data from human clinical trials.3 This classification correlated patient survival data with neoplastic cell morphology (large, small, cleaved, or blastic) and histologic pattern (follicular or diffuse).12 Neoplastic cell immunophenotype was not considered.

Common among these systems is the division of lymphoma types by grade. Low, high, and sometimes intermediate grades are described (Table 17-2).3,6 Features typical of low-grade lymphomas include small cell size, low mitotic rate, slow progression, long survival, and poor response to therapy. Features typical of high-grade lymphomas include high mitotic rate, rapid progression, and better response to therapy.

Table 17-2 Comparison of Lymphoid Neoplasms by Grade for Classification Schemes

| TUMOR GRADE | UPDATED KIEL FORMULATION | NCI-WF |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|