Chapter 118 Osteochondrosis

Osteochondrosis refers to a group of diseases that are characterized by aberrant development of the epiphyseal or physeal cartilage in growing animals. The cause of osteochondrosis appears to be multi-factorial; some of the factors that have been implicated include nutrition (overnutrition, excess dietary calcium, excess protein), genetics, exercise, environmental factors, and trauma (excessive mechanical loading), as the lesions frequently occur at the point of greatest loading of the joint.

ETIOLOGY

• Osteochondrosis at the physeal growth plate begins as an abnormal accumulation of viable hypertrophic chondrocytes that subsequently fail to undergo matrix mineralization, causing a slowing of growth, not complete cessation. In the dog, this primarily occurs at the distal ulnar physis (retained cartilage core or radius curvus), leading to the characteristic antebrachial deformities seen with asynchronous growth of the radius and ulna, namely shortening of the ulna, cranial bowing of the radius, valgus angulation, external rotation, shortening of the radius, and variable amounts of elbow and carpal incongruity.

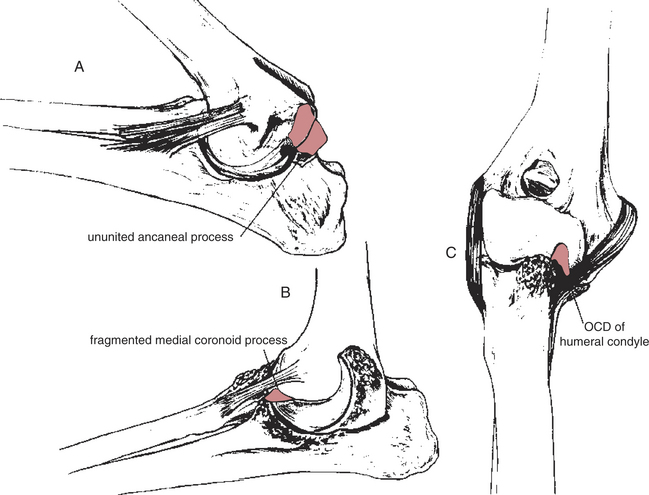

• Elbow dysplasia is a collection of diseases presumed to be a result of osteochondrosis, including ununited anconeal process (UAP), OCD of the medial portion of the humeral condyle, and fragmented medial coronoid process (FMCP) (Fig. 118-1).

OSTEOCHONDRITIS DESSICANS OF THE

Pathophysiology

• A defect in endochondral ossification results in a focal area of abnormal subchondral bone formation.

• The overlying cartilage fails to undergo endochondral ossification resulting in focal retention of cartilage instead of conversion to bone.

• This thickened region of cartilage becomes necrotic and weak, resulting in cartilage breakdown under normal loading conditions or secondary to trauma.

• Early in the disease process, the lesions of osteochondrosis affect only the epiphyseal cartilage, and the animal is asymptomatic.

• Once a fissure occurs in the thickened cartilage, it extends through the necrotic cartilage into the subchondral bone, allowing access of the synovial fluid to the subchondral bone.

• OCD results in two distinct joint abnormalities: joint incongruity secondary to malformation of cartilage and subchondral bone, and joint mouse formation.

• Cartilage flaps that remain attached may ossify, and the resulting bone remains viable as long as the flap is attached.

• Curettage of the chondral and subchondral lesion stimulates neochondrogenesis; however, the resultant fibrocartilage does not have the same material properties as the original hyaline cartilage, and is not as durable.

Clinical Signs

Hock

• Hind limb lameness characterized by a shortened stride and hyperextension of the tarso-crural joint.

Diagnosis

• The radiographic signs of osteochondrosis are well characterized and easily recognized in most cases; high-quality, well-positioned radiographs are necessary for an accurate diagnosis (see Chapter 4).

• Normal cartilage is not visible radiographically unless significant dystrophic calcification has occurred.

• Since OCD lesions consist of areas of relatively thicker cartilage than the surrounding cartilage and a failure of endochondral ossification of the underlying bone, the lesion is observed as a flattened or saucer-like “divot” in the subchondral bone.

Hock

• Radiographic identification of the lesion may be difficult due to the location of the lesion on the trochlear ridge.

• A dorsolateral-plantaromedial 45-degree oblique projection in full extension outlines the medial trochlear ridge of the talus.

Preoperative Considerations

• As the relative size of the osteochondral defect to the total joint surface area increases, the resulting joint incongruity also increases. Thus, a small defect in a large joint (shoulder) has less of an impact than in a small (hock) or complex (elbow or stifle) joint.

• The degree of osteoarthritis in the joint prior to surgery has an impact on long-term function; as the degree of osteoarthritis increases, function is diminished.

• Patients with small lesions and minimal osteoarthritis will have the best surgical result; conversely, patients with large lesions and severe osteoarthritis are less likely to benefit from surgery.

Surgical Procedures

Technique

• See respective chapters on shoulder, hock, and stifle disorders for a description of surgical approaches (see Chapters 102, 112, and 110).

• Debride the lesion to the level of subchondral bleeding bone utilizing a curette, a hand bur, or a motorized shaver.

• Debride the edges of the lesion peripherally to normal cartilage, and perpendicular to the subchondral bed.

Postoperative Care and Complications

• Apply a soft padded bandage for 3 to 5 days from the digits to the mid-diaphysis proximal to the incision to minimize postoperative swelling.