Chapter 110 Orthopedic Disorders of the Stifle

Common traumatic and congenital or developmental conditions of the stifle include patella luxation, cruciate disruptions, meniscal problems, collateral ligament injuries, and stifle luxation. The first three listed (excluding fractures) comprise 95% of stifle disorders in dogs and cats.

ANATOMY

Cranial Stifle

• The quadricep muscles, patella, trochlear groove and notch, patellar tendon, and tibial tuberosity are linearly aligned with the coxofemoral joint, talocrural joint, and paw. Normally there is no medial or lateral deviation of these structures.

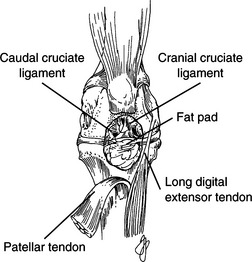

• Craniomedial and caudolateral ligamentous bundles constitute the cranial cruciate ligament, which originates on the caudomedial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle and inserts centrally on the tibial plateau caudal to the cranial intermeniscal ligament (Fig. 110-1).

• The caudal cruciate ligament originates on the craniolateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle and inserts on the caudocentral tibial plateau and medial popliteal notch.

• The long digital extensor tendon originates on the lateral femoral condyle cranial to the lateral collateral ligament and popliteus muscle.

• Retinacular fibrous tissue overlies the craniolateral and craniomedial aspects of the stifle joint.

Caudal Stifle

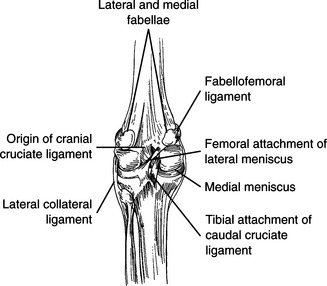

• Medial and lateral fabellae articulate intracapsularly with the femoral condyles and have strong fabellofemoral ligaments (Fig. 110-2).

• The medial meniscus is attached to the tibia and to the medial collateral ligament, whereas there are tibial and femoral attachments of the lateral meniscus.

GENERAL PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

• Client communication and cooperation and a successful return to function by the patient are enhanced by meticulous evaluation of the stifle joint preoperatively and intraoperatively. This facilitates an accurate diagnosis and selection of the appropriate procedure(s).

• Perform a thorough orthopedic examination, including the joints, bones, and muscles of the affected extremity.

Orthopedic Evaluation

Include the following maneuvers in palpation of the stifle:

• Palpation of the patellar tendon and parapatellar tissue should reveal a distinct “sharp” feel to the tendon edges. If they feel indistinct or “doughy,” this indicates stifle effusion, which is often associated with cranial cruciate rupture or degenerative joint disease secondary to rupture.

• Perform gentle, full range of stifle motion in normal flexion and extension, then repeat with internal and external rotation.

• With the femur held motionless with one hand and the proximal tibia held securely by the other hand, attempt cranial movement of the tibia after placing the stifle in slight to moderate flexion (drawer sign or Lachman test).

• With a finger held over the tibial tuberosity and the femur held securely, flex the hock to detect cranial movement of the tibia (tibial compression test). This test (and the Lachman test) indicates laxity of the cranial cruciate ligament.

• With the femur held motionless, determine internal and external movement of the tibia on the femur by grasping the hock and rotating the tibia. Normal range of motion is 20 to 30 degrees of internal rotation and 5 to 10 degrees of external rotation with the stifle in flexion.

• Exert medial and lateral digital pressure on the patella while putting the stifle through its range of motion to detect any patellar luxation.

• Exert pressure with the thumbs on the lateral side of the femoral condyle and proximal tibia, and then repeat on the medial side. Laxity of the collateral ligaments is detected by increased laxity of the joint space.

• Exert deep pressure of the stifle area with a fingertip to ascertain focal points of pain from soft tissue tears and bone bruises.

PRINCIPLES OF STIFLE SURGERY

• For the majority of the surgical procedures, place the dog in dorsal recumbency with the forelegs and unaffected rear limb secured. This gives good access to both sides of the stifle in a comfortable operating position. Place the instrument table over the dog’s trunk.

• Perform an arthrotomy of sufficient length to facilitate luxation of the patella. Using flexion and retraction, identify, inspect, and assess the articular surfaces of the patella, trochlear groove, tibial plateau, pericondylar, and supracondylar areas of the femur, patellar tendon, fat pad, and long digital extensor tendon.

• Place a small, sharp rake retractor (Senn) deeply behind the fat pad; retract cranially and inspect both cruciates.

PATELLAR LUXATION

Patellar luxations are classified as follows:

• Grade II—Spontaneous luxation occurs clinically. The patella can be luxated manually but reduces spontaneously or with gentle manipulation.

• Grade IV—The patellar luxation cannot be reduced manually. Often, flexure contracture has occurred and limb use is minimal.

Diagnosis

• History usually reveals intermittent rear-leg lameness. The lameness classically is characterized by rapidly alternating use and disuse of the limb, particularly during exercise.

Preoperative Considerations

• Evaluate the maximum internal and external rotation of the tibia on the femur. An increase in internal rotation of >30 degrees (often occurring in miniature breeds) indicates lateral retinacular laxity and the need for lateral imbrication.

• Patellar luxation procedures vary; some animals require only one step, whereas others need combined procedures.

• In some cases, combined parapatellar arthrotomy and release is necessary (to release means to diminish the pull or tension on tissue, often accomplished by incising perpendicularly to the line of tension).

Surgical Procedures

Equipment

• Double-action rongeur, bone curettes, and fine handsaw (hacksaw or Exacto saw #236), file, or rasp

Surgical Principles

• Reduce the patellar luxation and determine whether the tissues are tight on the side toward which the patella luxates and whether the tissues opposite the luxated side are very lax.

• If the former is present, perform combined parapatella arthrotomy and release to diminish the pull of the tissues.

• If the latter is present, combined arthrotomy and imbrication is indicated to tighten the lax side.

• With an adequately deep trochlear groove and no excessive tibial rotation, a release may be the only step needed to maintain the patella in its anatomic position.

• With a shallow trochlea, deepening can be accomplished by trochleoplasty, chondroplasty, or wedge resection. Techniques in which the articular cartilage is preserved (e.g., wedge resection) are preferred over those in which articular cartilage is not preserved.

• Correct excessive medial rotation of the tibia with a lateral antirotational nylon suture (fabella to tibial tuberosity drill hole; see Fig. 110-4) or by translocation of the tibial tuberosity laterally.

Techniques

Trochleoplasty

1. Following arthrotomy and inspection of the stifle, mark the medial and lateral boundaries of the planned trochlear groove by longitudinal cuts in the trochlear cartilage using a scalpel blade. To prevent fracture, try to obtain as much width and height as possible without weakening the remaining condylar bone.

3. Reduce the luxated patella for a trial fit and, if necessary, smooth the new surface with a fine, half-round file, or rasp. The depth of the new trochlea should accommodate the patella so that one-half to two-thirds of the patella’s height is in the groove.

4. Verify depth, smoothness, and stability by palpating the patella while putting the joint through its range of motion (flexion and extension with internal and external rotation of the tibia).

5. Close the synovia and joint capsule with appropriately sized monofilament nylon sutures in an interrupted cruciate pattern. If possible, perform partial-thickness closure whereby the suture is not within the joint. Close skin and subcutis routinely.

Chondroplasty

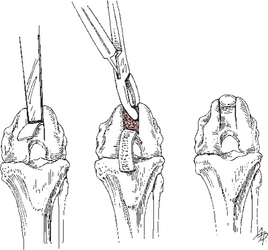

1. Make a trochlear outline, as described for trochleoplasty, down to subchondral bone (Fig. 110-3).

2. Using a thin, sharp, curved osteotome (Zimmer #2881-00-01, #2881-00-02) perform an osteotomy and create a rectangular cartilage flap with the hinge either proximally or distally. Include 1 to 2 mm of bone in the thickness of the flap.

4. After adequate depth is obtained, press the flap manually into the new groove. Pressure from the patella helps keep the flap in position.

Wedge Resection

2. With a power saw or fine handsaw, make two pie-shaped cuts at the peripheral borders previously outlined. Medial and lateral condylar osteotomies should meet centrally. Remove this central piece of bone and articular cartilage and place it in a blood-soaked sponge.

3. The shallowness of the trochlea determines the width of the next two saw cuts, which are parallel and peripheral to the first cuts. Remove these two pieces of bone. Place the trochlear segment with its intact cartilage into the recess; this results in a deeper trochlea with preservation of most of the articular surface.

Imbrication

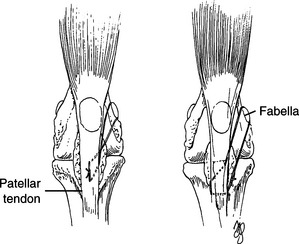

1. DeAngelis technique (fabella to patellar tendon; Fig. 110-4, left): Using non-absorbable monofilament suture, place mattress pattern sutures around the medial and lateral fabellae and running extracapsularly, engaging the distal patellar tendon.

2. Flo technique (see Fig. 110-4, right): Place the proximal aspect of the sutures similarly, but distally engage the proximal tibia through a transverse drill hole in the tibial tuberosity.

3. Place additional sutures, if needed, in a fan-like pattern, originating at the fabella and engaging the parapatellar tissue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree