CHAPTER 10 Ocular Infections

Infectious ocular diseases can occur as primary entities or as ocular manifestations of systemic disease. Most cases of surface ocular diseases are primary in origin, whereas intraocular diseases may be either primary or secondary. This chapter discusses the infectious diseases that affect equine eyes, beginning with surface infections and progressing inward.

OCULAR FLORA

Bacterial Isolates from Normal Eyes

The normal ocular microflora is predominantly nonpathogenic gram-positive organisms, although some gram-negative and fungal organisms are also present.1 Normal ocular flora may vary depending on the environment, husbandry, geographic region, season, and climatic factors.1–3 Organisms typically recovered from healthy equine eyes include Bacillus cereus, Streptococcus equi subsp. equi, S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus, other streptococci, Corynebacterium spp., Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis.1–6 Gram-negative organisms isolated from healthy equine eyes include Moraxella spp., Neisseria, and Acinetobacter.1,3,4 Fungi may be isolated from the conjunctival sac in 95% of equine eyes.7 The most common fungal flora isolated vary by study, but Aspergillus spp. and Cladosporidium spp. are consistently reported, in addition to unidentifiable and dematiaceous molds, Chrysosporium spp., and Alternaria spp.4,6,7 Fungal organisms may contribute to pathology when the corneal epithelium is ulcerated or eroded.1,7,8 Some microflora are considered environmental contaminants, and these isolates may vary depending on season, geography, and management.1,2,7

Bacterial Isolates from Diseased Eyes

In a study of 38 eyes from 37 horses with ulcerative keratitis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the most common bacterium isolated (10 of 34 isolates).9 Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., and Citrobacter spp. were also frequently isolated. In a study of 123 horses with ulcerative keratitis or conjunctivitis, bacteria were isolated from 98 eyes.10 Streptococcus spp. were isolated from 54 eyes (43.9%); β-hemolytic streptococci comprised 32 of the 54 isolates. Staphylococcus spp. were isolated from 30 eyes (24.2%) and Pseudomonas spp. from 17 eyes (13.8%). Although gram-negative bacteria are often perceived as causing severe corneal infection, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus infections may also cause severe corneal disease.10–12

Fungal Isolates from Diseased Eyes

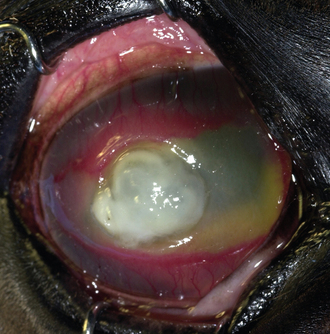

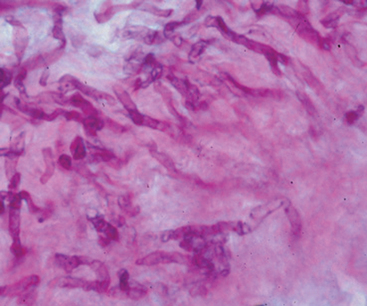

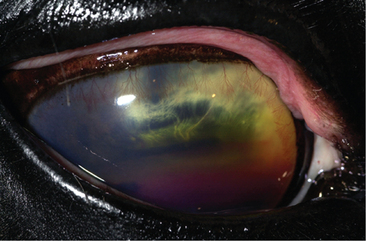

Fungal keratitis can be a vision-threatening disease, with reported maintenance of vision in 53% to 64% of affected horses15–18 (Fig. 10-1). Despite these reports, most veterinary ophthalmologists consider prognosis for vision favorable with aggressive surgical and medical management.13,14 Aspergillus spp. and Fusarium spp. are typically identified as etiologic agents of equine keratomycosis (Fig. 10-2). Fungal keratitis appears to be most common in the summer and fall,10,13–22 although this may vary by geographic location.

PRIMARY OCULAR INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Blepharitis

Infectious blepharitis, inflammation of the eyelids, may occur secondary to bacterial, viral, fungal or parasitic infection. Regardless of cause, horses with blepharitis present with swollen inflamed eyelid(s). In the horse, bacterial blepharitis is the second most common type of blepharitis after trauma.23 Bacteria implicated as etiologic agents of equine blepharitis include Moraxella spp.24 and S. equi subsp. equi. Bacterial blepharitis is usually unilateral and subacute, with mucopurulent discharge or abscess formation.25 Papovavirus and horse pox can cause unilateral or bilateral blepharitis, chronic papillomas, or pustular dermatosis.25 Numerous fungal organisms cause a blepharitis that is usually unilateral, with chronic alopecia, scaling of the skin, granulomas, draining tracts, or granulation tissue. Specific organisms include Trichophyton spp., Microsporum spp., Cryptococcus mirandi, Aspergillus spp., Rhinosporidium seeberi, Histoplasma farciminosus (epizootic lymphangitis), and phycomycosis.23,25–28

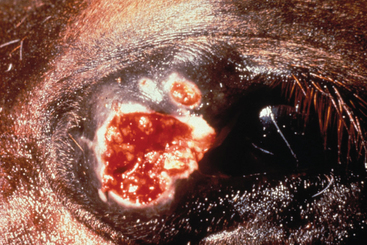

Parasitic blepharitis may be unilateral or bilateral with pruritus and can have a gritty caseous discharge. Aberrant migration of the larvae of Habronema muscae, H. microstoma, or Draschia megastoma can result in periocular or eyelid lesions with a raised, irregular, yellow appearance often referred to as “sulfur granules.”29 Biopsy of the affected area can aid in diagnosis to rule out other causes of ulcerative skin lesions, such as neoplasia, proud flesh, and bacterial or fungal granulomas.30 An eosinophilic infiltrate within a fibrous stroma will be evident histologically.31 Other parasites that can cause blepharitis include Demodex spp. and Thelazia spp.25 Parasitic ocular manifestations are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Conjunctivitis

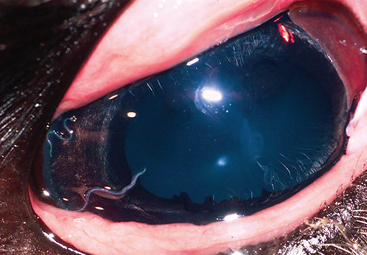

Primary conjunctivitis in the horse is uncommon but associated with numerous infectious etiologies. Differentiation of primary conjunctivitis from secondary conjunctivitis resulting from other diseases (e.g., dacryocystitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, keratitis, uveitis, glaucoma) is important.25 Clinical signs associated with conjunctivitis are nonspecific to the underlying cause and include conjunctival hyperemia and chemosis. Other clinical signs may include follicle formation (Fig. 10-3), mucopurulent discharge, and depigmentation of the lateral aspect of the bulbar conjunctiva.

Fig. 10-3 Equine eye with numerous lymphoid follicles in perilimbal region appearing as tiny vesicles.

(Courtesy Dr. Michael Davidson.)

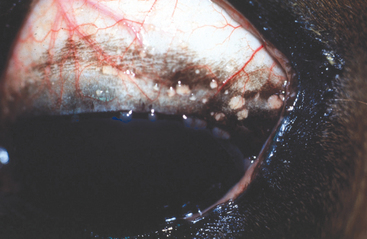

Several bacterial species have been identified as primary etiologic agents of conjunctivitis in horses. Streptococcus equi subsp. equi is associated with regional lymphadenitis (i.e., strangles), mucopurulent nasal discharge, and conjunctivitis32 (see Chapter 28). Moraxella equi24 and Chlamydia and Mycoplasma spp.33 have also been identified as causes of primary conjunctivitis in horses. Histoplasma farciminosus (epizootic lymphangitis) may result in ulcerative conjunctivitis.26 Aspergillus spp. and Rhinosporidium seeberi can cause granulomatous conjunctivitis,25,26 and blastomycosis has been associated with nasolacrimal disease.26 Equine herpesvirus types 1 and 2 (EHV-1, EHV-2) can cause recurrent conjunctivitis with or without corneal ulceration34–37 (see Chapter 13). Adenoviral infection may result in conjunctivitis with mucopurulent ocular and nasal discharge, keratouveitis, and systemic disease26,38 (see Chapter 16). Equine viral arteritis may cause blepharedema and conjunctivitis25,39,40 (see Chapter 14). Parasitic conjunctivitis can be caused by Thelazia lacrimalis, Onchocerca spp., Habronema spp., ophthalmomyiasis externa (Oestrus ovis), and Trypanosoma evansi. Thelazia lacrimalis can cause mild conjunctivitis and epiphora41 (Fig. 10-4). Onchocerciasis results in depigmentation of the lateral aspect of the bulbar conjunctiva with or without uveitis42 (Fig. 10-5). Habronemiasis results in granuloma formation with mucopurulent discharge23, 43 (Fig. 10-6). (See later discussion for more information on parasitic ocular manifestations.)

Keratitis

Infectious corneal disease in horses most often occurs secondary to corneal trauma but can also be a manifestation of primary ocular disease or systemic disease. Normal uncomplicated corneal epithelial wound healing in the horse occurs at an average rate of 0.6 mm/day.44 Healing of corneal stromal wounds is more complicated and involves collagen remodeling and proteoglycan synthesis, eventually resulting in restoration of tensile strength.45 The prominent anatomic location of equine eyes and the normal opportunistic bacterial and fungal periocular flora predispose equine corneas to infectious keratitis.

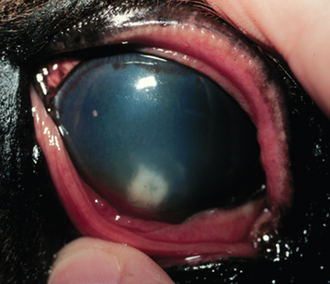

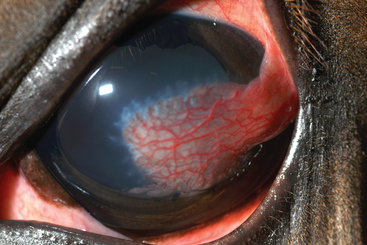

Infectious keratitis caused by trauma may or may not be ulcerative and may be caused by opportunistic bacterial or fungal organisms, or a combination of these. Nonspecific signs of keratitis include pain (blepharospasm, photophobia, epiphora), serous to mucopurulent ocular discharge, corneal edema, variable corneal vascularization, loss of stromal integrity (melting or keratomalacia), and secondary anterior uveitis (aqueous flare, hypopyon, miosis). Horses with infectious ulcerative keratitis will have loss of corneal epithelium and variable stromal loss. Full-thickness loss of corneal stroma that breeches Descemet’s membrane will usually be plugged with fibrin and iris prolapse, with or without aqueous leakage (Fig. 10-7). This is a surgical emergency, and an ophthalmologist should be consulted. Horses with infectious nonulcerative keratitis will have an intact corneal epithelium, but cellular infiltration will be evident within the corneal stroma, that is, corneal abscess (Fig. 10-8). Fungal virulence factors may inhibit corneal vascularization46,47 and reduce neutrophil infiltration and cell-mediated phagocytosis,48 impeding healing and necessitating aggressive medical and surgical intervention. In horses with progressive or perforated corneal ulceration, keratectomy with a conjunctival pedicle flap will provide diagnostic and therapeutic benefits to the patient. Stromal loss that has progressed beyond three-quarters depth may be treated with debridement, followed by synthetic or heterologous corneal grafts and a conjunctival pedicle flap (Fig. 10-9).

Primary infectious keratitis that is not associated with trauma may be caused by equine herpesvirus (EHV) and other respiratory viruses (e.g., adenovirus, influenza, Borna virus). Each of these diseases is discussed separately elsewhere in this text. EHV keratitis typically presents as superficial punctate or dendritic lesions secondary to EHV-2 infection.34,37,46,50 Acute cases will be quite painful (blepharospasm, serous epiphora) with chemosis and conjunctival hyperemia.46 Recurrent cases may exhibit corneal vascularization.

Diagnostic evaluation of infectious ulcerative keratitis may include evaluation of corneal cytology, culture and sensitivity, and histopathology. Nonulcerative keratitis is difficult to assess by cytology and culture and sensitivity because of the intact corneal epithelium. Definitive diagnosis of both these disorders can often be obtained at surgery by biopsy of the infected tissue. A rapid and new diagnostic test available at the author’s institution is quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for fungal deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). This assay can also be performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues for retrospective analysis and may ultimately provide a more rapid and precise identification of corneal pathogens.50a The superficial or punctuate lesions of EHV can be identified by rose bengal stain but not always with fluorescein stain. EHV keratitis can also present as anterior stromal or epithelial punctate opacities without ulceration. This makes diagnosis difficult, and other differential diagnoses should be considered, including fungal keratitis.46 Diagnosis of EHV keratitis is difficult, but cytology early in the course of disease may be helpful.

Infectious ulcerative keratitis that has not progressed beyond one third of the stromal depth can be treated medically. Depending on the underlying cause, topical antifungal medications (e.g., miconazole, natamycin, itraconazole with DMSO) and oral antifungal medications (e.g., fluconazole) may be necessary. All horses with corneal ulceration should be treated with topical cycloplegics (e.g., atropine, q12-24h), oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g., flunixin meglumine) for pain and secondary uveitis, and topical antibacterial medications (e.g., neomycin-polymyxin-bacitracin, neomycin-polymyxin-gramicidin, chloramphenicol, or ciprofloxacin, q4-6h), to prevent opportunistic bacterial growth.

Melting corneal ulcers can rapidly become surgical emergencies and should be treated aggressively (Fig. 10-10). The underlying infectious causes of melting corneal ulcers include Pseudomonas spp., β-hemolytic streptococci, and fungal infections. Neutrophilic infiltrates and previous corticosteroid use can predispose to melting corneal ulcers. Medical management should include compounds with antiproteolytic activity in addition to the medications just listed and appropriate antibacterial medications for the specific bacteria. Several antiproteases have been recommended for treatment of melting corneal ulcers, including 0.2% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 5% to 10% N-acetylcysteine, autologous serum, and topical or oral tetracycline or doxycycline. If a member of the tetracycline family is used topically, because of its bacteriostatic nature, its administration should be staggered with the bactericidal antibiotic used by at least 1 hour. Most horses with melting corneal ulcers should be examined by a veterinary ophthalmologist and will likely require surgical intervention.

Topical corticosteroids should be avoided in all horses with keratitis. Indolent or nonhealing corneal ulcers should be managed by debridement and topical antimicrobial and cycloplegic medications as well as oral NSAIDs. Grid or punctate keratotomy should be avoided because of possible underlying fungal infection.49

Therapy for EHV keratitis includes topical antiviral and NSAID therapies. Idoxuridine (0.1%) and trifluridine (0.3%) limit viral replication but do not kill the virus; therefore, they should be used between 4 and 12 times daily for 3 to 5 days until the condition stabilizes, then 3 to 6 times daily thereafter. Some formulations of these medications can be irritating to the eye. Topical NSAIDs include 0.03% flurbiprofen and 0.1% diclofenac and are helpful for secondary uveitis and inflammation, but they should be used with caution because they may cause recrudescence of viral keratitis in human patients. Topical corticosteroids should be avoided in horses with EHV keratitis, as well as most horses with keratitis. Oral l-lysine is useful adjunctive therapy in human and feline patients with herpetic keratitis because it limits replication of the virus as a result of its competitive antagonism with arginine.46 There are no dose guidelines for l-lysine in horses, but empiric supplementary doses of 10 to 30 g once daily indefinitely have been suggested. Viral keratitides that are not associated with EHV are uncommon in the United States but can be treated similarly to EHV keratitis with topical antiviral and NSAID therapy.

Uveitis

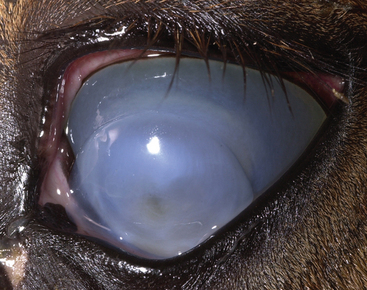

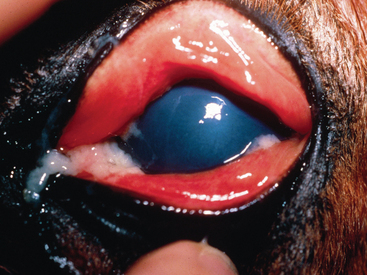

Uveitis is inflammation of the uveal tract, which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Anterior uveitis refers to inflammation of the iris and ciliary body, posterior uveitis refers to inflammation of the choroid, and panuveitis refers to inflammation of all components of the uvea. Clinical signs of active uveitis are nonspecific and include pain (blepharospasm, photophobia, epiphora, ocular discharge), conjunctival hyperemia, scleral injection, corneal edema, keratic precipitates, aqueous flare, hypopyon, hyphema, fibrin in the anterior chamber or vitreous, iris color change, and miosis (Figs. 10-11 and 10-12). Chronic changes include atrophy of the corpora nigra, cataract, fibrosis of the iris, endothelial scarring, phthisis bulbi, and glaucoma. Infectious systemic causes of uveitis include viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and parasites.51 Specific viral causes of uveitis include equine influenza virus, EHV-1, equine viral arteritis, and equine infectious anemia virus. Bacterial causes include Leptospira spp., Brucella spp., Streptococcus spp., Rhodococcus equi (Fig. 10-13), and Escherichia coli. Toxoplasma gondii may cause uveitis in horses. Parasitic etiologies include Onchocerca spp. and Strongylus spp. More detailed information regarding ocular manifestations of these organisms can be found later in this chapter.

Equine recurrent uveitis (ERU) is an immune-mediated disorder that is the leading cause of blindness in horses. Although the recurrent episodes of ERU are not directly caused by reinfection with microorganisms or parasites, numerous bacterial, viral, protozoal, and parasitic organisms have been implicated in initiating the syndrome (see Chapter 34 for discussion of the association of leptospirosis with ERU).52

SYSTEMIC DISEASES WITH OCULAR MANIFESTATIONS

Viral Diseases

Alphavirus Encephalitides

Alphaviral encephalitides (eastern, western, and Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis) are transmitted by mosquitoes and have a typical geographic distribution63 (see Chapter 20). When the brain stem is involved, nystagmus, strabismus, pupil dilation, and head tilt occur.64 Systemic clinical signs include fever, conscious proprioceptive deficits, and behavioral changes. In the later stages of disease, progressive signs of cerebral or cerebrocortical and cranial nerve dysfunction may be seen and include facial, lingual, and pharyngeal paralysis; ataxia; hypermetria; circling and proprioceptive deficits or paresis of the trunk and limbs; as well as blindness.65 Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis for horses with alphavirus encephalitis are discussed in Chapter 20.66,67

Equine Viral Arteritis

Equine viral arteritis (EVA) is caused by a virus of the Arteriviridae family and is spread through inhalation of aerosolized virus or through sexual contact68 (see Chapter 14). Horses with clinical disease may exhibit signs of upper respiratory disease, edema, fever, and abortion 3 to 8 weeks after infection.69 Ocular signs include serous to mucoid ocular discharge, conjunctivitis, corneal opacity, photophobia, and periorbital edema. Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis for horses with EVA are discussed in Chapter 14.70

Equine Infectious Anemia

Equine infectious anemia (EIA) is a chronic disease of horses caused by a virus belonging to the Lentivirus genus of the family Retroviridae (see Chapter 23). Although most infected horses show no recognizable clinical signs, other horses may present with signs that include recurrent fever, weight loss, edema, thrombocytopenia, and anemia.71 Thrombocytopenia can result in ocular lesions, including conjunctival and intraocular hemorrhages. Choroiditis has also been described in horses with EIA.72 Horses with subacute to chronic disease develop anemia and may experience recrudescent cycles of disease. Infected horses remain infected for life. Therefore, seropositive horses are considered infected. Diagnosis, prognosis, and prevention of EIA are discussed in Chapter 23.

Rabies

Rabies is a rapidly progressive, fatal disease caused by a neurotropic virus of the family Rhabdoviridae that may affect most warm-blooded mammals (see Chapter 19). Ocular signs rarely occur, or are not noticed, but may include prolapse of the third eyelid, blindness, nystagmus, and strabismus, most likely caused by diffuse cerebrocortical edema and hemorrhage.72–74 Euthanasia is recommended because no treatment is available. Appropriate caution should be taken with all animals with neurologic signs, especially those not vaccinated for rabies. The most reliable diagnostic test remains the fluorescent antibody test performed on brain tissue.73

African Horse Sickness

African horse sickness (AHS) is a noncontagious, arthropod-borne orbivirus that affects all Equidae, although mules, donkeys, and zebras are less susceptible than horses75 (see Chapter 15). It is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa but has not been documented in North or South America. Ocular signs may include chemosis (conjunctival edema) and bulging of the supraorbital fossae.76

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree