Chapter 116 Neoplasia of Thoracic and Pelvic Limbs

Tumors of the appendicular skeleton can occur either as a primary or metastatic lesion. Primary bone tumors occur most commonly in middle-aged and older animals. However, younger dogs 18 to 24 months of age can be affected.

Etiology

Primary Skeletal Neoplasms

Osteosarcoma

• The distal radius is the most common site for OSA, making up 40% of all skeletal OSA. Other common sites include the proximal humerus, distal femur, and proximal tibia.

• Although 80% to 90% of dogs lack radiographic evidence of pulmonary metastases at time of diagnosis, most dogs are euthanized due to complications associated with metastatic lung disease.

• Large- and giant-breed dogs are over-represented in most studies. Only 5% of OSA occurs in dogs weighing less than 15 kg.

• One study found that OSA in small-breed dogs behaves differently than in their large-breed counterparts, representing less than 50% of all skeletal neoplasms and with no apparent predilection for the distal radius. The proximal humerus is the most common site in the small-breed dog.

• Appendicular OSA in cats behaves less aggressively than canine OSA, with affected cats surviving a mean of 14.8 months following amputation. The hind limb is more commonly affected in the cat.

• Cisplatin, carboplatin, and doxorubicin are chemotherapeutic agents frequently used in treatment of OSA. Survival rates reported with chemotherapy are 45% survival to 1 year, and 30% 2-year survival.

• Poor prognostic indicators in dogs with OSA include a preoperative alkaline phosphatase level greater than 110 U/L, OSA in young patients, high tumor grade, and radiographic evidence of pulmonary metastases.

Chondrosarcoma

• Unlike OSA, surgical resection of chondrosarcoma is associated with an increased long-term survival when compared to non-surgical management.

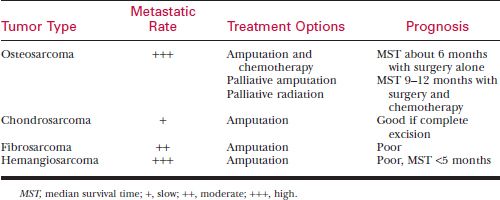

See Table 116-1 for biologic behavior, treatment, and prognosis of the most common canine malignant appendicular skeletal tumors.

Primary Soft Tissue Neoplasms

Synovial Cell Sarcoma

• Radiographs reveal an osteolytic pattern associated with a joint. Classically, this tumor crosses the joint space. This differs from primary tumors of bone, which characteristically do not cross the joint space.

• Histologic grading carries prognostic significance, as tumors with higher biologic grading are more likely to metastasize. The metastatic rate varies from 20% to 70%, depending on histologic grading.

Metastatic Neoplasia

• Any neoplasm may metastasize to bone, but carcinomas are more likely to metastasize to bone than sarcomas. In particular, urogenital neoplasms such as prostatic carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, and mammary carcinomas tend to metastasize to bone.

• A thorough diagnostic workup (bloodwork, three-view chest radiography, abdominal ultrasonography) is essential to determine the primary source of neoplasia.

Clinical Signs

• Clinical signs are variable and range from a subtle lameness and non-painful swelling to a non–weight bearing lameness with obvious limb deformation.

• Occasionally, acute lameness will be seen secondary to pathologic fracture through the diseased bone.

Diagnosis

• A presumptive diagnosis is usually made based on signalment, history, physical examination, and radiographic findings.

• A thorough physical examination, complete blood count, serum biochemical profile, and urinalysis are important to assess the patient’s overall health status and check for concurrent conditions that may affect treatment options.

Diagnostic Imaging

• Obtain a three-view thoracic radiographic study (i.e., right lateral, left lateral, and ventrodorsal or dorsoventral views) to evaluate the patient for pulmonary metastasis.

• Chest radiography and nuclear imaging are two modalities that, when used together, detect metastasis in about 18% of cases. Availability of nuclear imaging is limited in private practice.

• Other advanced imaging modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are useful in locating metastasis to lung and other extra-skeletal sites. Use of imaging to estimate tumor margins is important in limb-sparing surgeries and in radiation therapy planning.

Biopsy

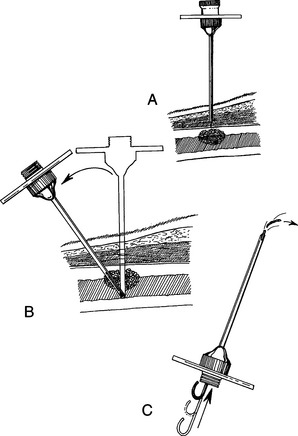

• Definitive diagnosis requires representative biopsy performed either using a bone core biopsy (Jamshidi needle, Michel trephine, or open-incisional) in the radiographic middle of the lesion or a wedge biopsy if the mass is soft tissue in origin (Fig. 116-1).

• Jamshidi needle biopsy has an accuracy rate of 91.9% for detection of tumor versus other disease processes and 82.3% for diagnosis of exact tumor type.

• Perform a fine needle aspirate on all enlarged lymph nodes and evaluate cytologically for metastasis.

Treatment

Surgery

• Although some small or benign tumors may be treated by local resection, most appendicular neoplasms require complete or partial amputation of the affected limb, primarily for palliation of pain (see discussion of amputation later in this chapter). Evaluate the patient’s other limbs to ensure that adequate function can be carried out with the remaining three limbs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree