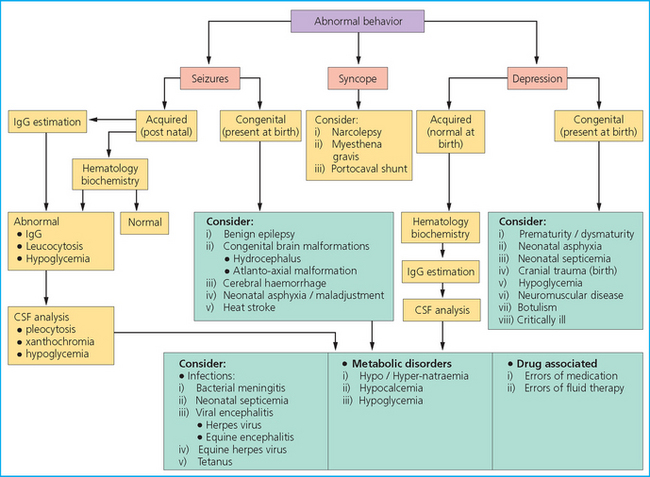

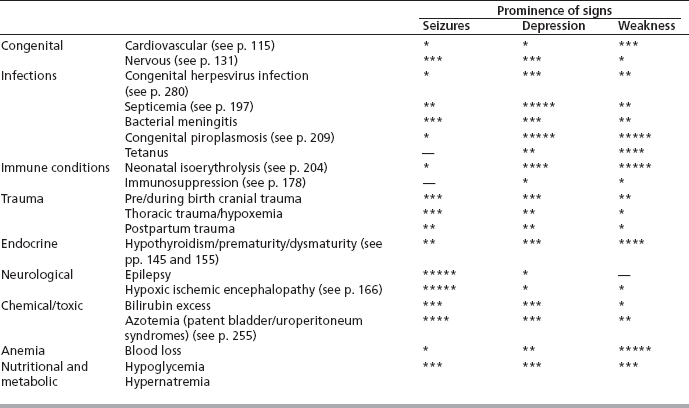

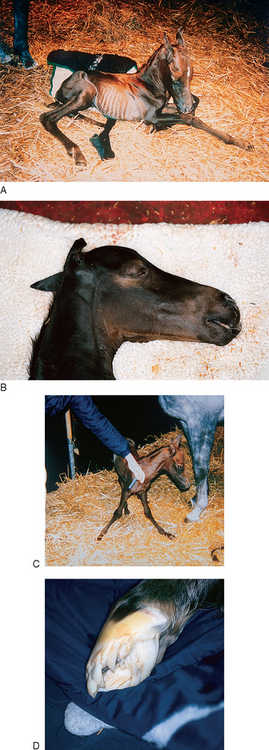

Chapter 6 A careful clinical examination is obligatory in every foal presented. The value of a prepared form for the recording of the findings cannot be overstated (see p. 476). It is important to assess both the gestational age and the clinical appearance together as the normal gestational length is variable in the horse and foals may be obviously abnormal at full or even extended gestational age. This makes for very unpredictable results from induced parturition.1 Generally an induced delivery should not be regarded as normal even when the induction is performed for purely elective reasons in a full term mare. A 365-day gestation can be normal in some horses whereas in others it is the result of persisting placental insufficiency and the results of the pregnancy are equally unpredictable. Although the terms ‘prematurity’ and ‘dysmaturity’ are applied to different circumstances relating to the duration of gestation, the clinical signs of the two states are for all practical purposes the same. These two ‘conditions’ can therefore be grouped together under the term ‘unreadiness for birth’.2,3 Survival rates for premature or dysmature foals are lower than normal in spite of the extra effort that can be brought to bear. Premature foals (gestational age 300–320 days) have a 70–75% survival rate.4 The definitions of prematurity and dysmaturity are: • Prematurity: a foal born prior to 320 days is classified as premature. • Dysmaturity: a foal born within the normal gestational range (320–345 days) but showing the signs normally associated with prematurity. These foals are often termed ‘immature’ or ‘unready for birth’ in that they are apparently have little ability to maintain body homeostasis and show slow adaptation to extrauterine conditions. Foals may even have a prolonged gestational age (> 350 days). • For the most part, foals that do not establish normal righting reflexes and a normal suck reflex will die without intensive care. • Those that show normal righting and a strong suck reflex will often progress satisfactorily until 24 hours and then will rapidly fade and die unless strong intervention is applied. • If the foal can stand and suckle within 2–3 hours of birth the prognosis is better but such a foal may need intensive care if it is to survive normally. • The detailed management of a dysmature or premature foal is described on pages 158 and 405. This is thought to be caused by endocrine or placental dysfunction, or both, or inadequacy. Twins are always dysmature (the complete placenta is required for normal development of one foal and neither had the required placental area) (see p. 46). Prematurity/dysmaturity can be recognized by: Figure 6.1 (A) Small underweight foal lying down; (B) domed forehead and curled soft ears; (C) foal standing with splayed legs typical of hypoplastic bones; (D) slipper foot typical of prematurity. • Underweight for type (small body size for age/type) at birth. Although many foals are not weighed accurately most of these foals are obviously small and underweight. They may be obviously dehydrated at birth, which adds to the weight deficit. Twins are, of course, invariably underweight and small. • Slow to stand, poor suckling time and enthusiasm. • Bulging prominent ‘domed’ forehead and eyes are common (especially noticeable in twins). However, this sign can be misleading on sign because some breeds (notably the Welsh pony and the Arabian) naturally have prominent foreheads. • Weak musculature and slack/lax flexor tendons (front limbs in particular) with a noticeably long pastern angle. Increased range of joint motion. Most of these will correct fairly quickly. • Collapsed tarsal or carpal bones due to poor/delayed ossification with consequent angular and flexural deformities. • The tongue often has a prominent red/orange color rather than the normal salmon-pink color. • Mucous membranes may appear pale (marginal anemia may be detected clinically; see p. 212). • The coat has a fine, silky texture and the nose/ears are soft and pliant. • Dehydration is relatively common either at birth or it develops shortly afterwards. • Uncoordinated limb movements reflect neurological and muscular dysfunction. • A slow respiratory rate or an abnormal respiratory pattern reflecting the likely fetal atelectasis (failure of lung expansion and maturation with surfactant deficits)6: • Progressive deterioration in environmental awareness and maternal recognition is a common feature. Abnormal mentation reflects failure of neurological adaptation or the results of progressive oxygen starvation in the central nervous system. Affected foals may be, or may become, blind. • Immature foals are often born emaciated and dehydrated. Sometimes this is a result of diarrhea but more often reflects serious metabolic derangement of the adrenal glands and kidneys. • Diarrhea may be seen; premature and dysmature foals are much more susceptible to infection than normal foals. • History: establish whether there are reasons for premature delivery/dysmature appearance such as evidence of fetal infection, placentitis, placental insufficiency, twins, etc. History of maternal illness or premature milk leakage, or both. • Clinical signs: as above. Evidence of fetal sepsis (uveitis/pneumonia/joint ill). These foals usually require critical care (see p. 409), supportive treatment and support of adrenocortical function. Nursing is critical; without this there is little or no point in simply administering drugs. If the foal’s adrenal gland appears unresponsive to the ACTH stimulation test then exogenous cortisol needs to be administered – a single dose of hydrocortisone should be given immediately (0.5 mg/kg i.v. or i.m.). Many clinicians continue corticosteroid therapy alongside the depot ACTH treatment (below). This therapy is controversial because (a) it has unknown efficacy, (b) it may have a negative feedback on the ACTH stimulated endogenous cortisol production and (c) any corticosteroid use has a risk of inducing gastric ulcers and immunosuppression. However, if the adrenal gland has been shown to be unresponsive to ACTH stimulation then it would appear logical that some exogenous corticosteroid administration is essential until adrenal function improves. In practice, the same regimen is used as that for treatment of cerebral oedema (see p. 166) is used for this purpose and has appeared helpful – dexamethasone given at a dose of 4 mg total dose/50 kg foal i.m. q 12 h, and maintained for several days. The dose should be tailed off. • intranasal oxygen if hypoxemic (see p. 385) • maintenance in sternal recumbency, regular turning from side to side and encouragement to stand • the efficacy of artificial and natural surfactant products (used for hyaline membrane disease in human premature babies) is debatable and most of the products are restrictably expensive. Colostral intake and monitor efficiency of absorption should be ensured. The gastrointestinal tract of the premature foal is often intolerant of oral feedings. However, the caloric requirements of the premature foal are probably great and, therefore, a combination of enteral and parenteral nutrition is usually required (see p. 427). In addition, the premature foal often has incomplete skeletal ossification and, although no specific data exist, it may be wise to supplement premature foals with calcium and phosphorus (e.g. FoalAide, Equine Buckeye Nutrition, Baileys Horse Feeds, W. Yorks, UK). Antibiotics are very important either prophylactically or to treat existing infection. Every effort to identify the bacteria responsible must be made, by cultures of blood, tracheal aspirates, intravenous catheter tips, etc. For guidelines on antibiotic choice see page 193. It is best to have a completely normal WBC count and differential and plasma fibrinogen/ serum amyloid A level before discontinuing antibiotics. It is not unusual for hematology to remain abnormal for as long as 2 to 4 weeks. Closely monitor the foal for nosocomial infections. If a fever spike is noted, if the WBC count changes dramatically, or if there is clinical deterioration, additional bacterial cultures are warranted and a change in antibiotic therapy may be necessary. Management of limb deformities is discussed on page 289. Exercise must be limited if hypoplasia of the carpal or tarsal bones is present. This tends to be poor and frequently foals develop secondary complications such as sepsis or longer-term developmental bone disease (see p. 197). These foals often do well for 24–48 hours and then fade, and respiratory maturation is often a crucial factor such that atelectasis is often limiting. No single parameter should be used to obtain a prognosis – rather the whole range should be employed and those with several ‘unfavorable’ signs are usually in need of intensive care and may need to be moved to a hospital situation (see Table 6.1). Table 6.1 Prognostic indicators for prematurity and dysmaturitya bNote that placentitis can be seen as a favorable parameter because several studies5,9 have now shown that placentitis may switch on the fetal adrenal gland prematurely allowing sufficient cortisol production for extrauterine survival of these premature foals. Avoid induction of parturition unless necessary, as readiness for birth may be difficult to predict. Measures that result in a reduction in placental insufficiency will result in an improved chance of a normal gestation and a normal foal. However, it is important to balance the threat of a deteriorating placental environment with the risks of early delivery. Repeated careful prenatal assessment of the foal by combinations of ultrasonographic, electrocardiographic and clinical assessment (of fetal movement and size) can be helpful (see p. 25). It is probably a sensible precaution to make these assessments in all high risk mares. An abnormal placenta can sometimes be detected with transabdominal ultrasonographic examination.10 Other aspects of the fetus that are suggestive of fetal stress include the heart rate and size, fetal movement and the volume and character of the allantoic fluid. Young foals have an inherently low seizure threshold11 and premature and dysmature foals have a high tendency to seizures.12 A single seizure should not be taken necessarily to indicate serious disease or a longer-term problem. Seizures are much more commonly secondary to other disorders. Septic foals, maladjusted foals and those affected by neonatal hypoxia–ischemia syndrome or intracranial traumas also have an increased tendency to seizures. The particular difficulties of a detailed clinical examination of foals make it essential that a meticulous clinical and a specific neurological examination are performed (see p. 476). It is frequently necessary to perform sequential examinations to establish progression of signs and in some cases the subtle signs may become more obvious on a second occasion. The interval between examinations needs to be relatively short and repeated clinical assessments at 1–2-hour intervals can be a valuable help. Undue delays between the examinations can, however, be catastrophic because some conditions will change rapidly. Supportive tests including hematology and biochemistry are invariably required. Most clinicians will always perform a blood culture in aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid is useful but collection is problematical and so this is seldom performed outside specialized hospital conditions (see p. 387). Abnormal behavior patterns include variations of one or more of the following: 1. Seizures: a seizure (convulsion, fit or ictus) is an abnormal behavioral manifestation of abnormal electrical activity in the forebrain that result in involuntary, spontaneous, paroxysmal muscular activity and varying degrees of unconsciousness. 2. Depression: this signifies involvement of the forebrain. Mentation and demeanor are the main features to use in diagnosis. Conditions may be primary or secondary. 3. Recumbency: this may be a result of musculoskeletal problems but if the foal has no orthopedic reason to be recumbent then weakness is usually the cause. Weakness has a number of neurological and metabolic causes. For example a hypoglycemic foal or a profoundly anemic foal will be very weak and will become tired rapidly. Usually a weak foal can stand, but only for a short time, and its exercise tolerance is very limited. 5. Loss of awareness (usually first manifested as loss of maternal recognition or off-suck). Abnormal behavior that is present from birth can be due to congenital conditions (see p. 131) but a larger proportion is the result of potentially critical acquired disease. Birth asphyxia syndrome, infections and trauma are probably the commonest causes of abnormal behavior in newborn foals. A significant number of foals have signs that are either neurological or resemble neurological disease but recover spontaneously. These may be associated with adaptive changes or be due to immaturity of development. For example, some foals are born blind but vision becomes normal within a few hours of birth. The attendant may not even notice that there was anything ‘wrong’ at birth. The neurological examination of the foal carries special problems. Details of a suitable protocol are shown in Figure 6.2. The value of a full and thorough examination cannot be overstated. In the assessment of any neurological disease the ‘time versus sign’ graph is a useful aid to both the prognosis and the assessment of therapy. This graph represents the change in the severity of a particular sign (or the combination of signs if a syndrome is being assessed) with advancing time; its use depends heavily on the repeated critical and detailed neurological examination and to this end a prepared form can be a significant advantage (see p. 483).13 The primary objective of the neurological examination is to establish: • Whether there is in fact a neurological disease: Is it a primary neurological disease that could be assessed on its own, or is it a secondary disorder that will need to be treated indirectly by management of the primary condition? • Where the abnormality might be located: is there a single lesion, or are there multiple foci and where are these located within the neurological system? • What type of disease process is involved: is the condition of infectious origin or non-infectious? If the former is it a viral, bacterial, protozoal or parasitic disease? If the latter, is it a congenital or developmental disorder, is it immunological in origin or is it related to changes in the cardiovascular, neurological or metabolic status of the foal? Hypoxic–ischemic problems in the perinatal and birth period and traumatic disorders are relatively common and often there is no outward evidence of this. • Rational therapeutic options: therapy relies upon management of the signs and the repair of damage. Although there may be serious damage to the nervous system, some cases recover well enough if suitable care is given. Important aspects of the assessment of a suspected neurological case include: 1. Full history of mare and foal: including prepartum events for both mare and foal. 2. Full clinical examination of: 3. Full hematological analysis: some of the important secondary neurological diseases have significant hematological changes and in any case all sick foals should be subjected to a detailed hematological and biochemical analysis because the clinical signs are not always clear. 4. Cerebrospinal fluid sampling: samples of cerebrospinal fluid can be obtained from the lumbosacral puncture under strictly aseptic precautions but this site is usually difficult in young foals. Cisternal puncture requires general anesthesia or very deep sedation and full aseptic precautions (see p. 387). Conditions commonly or occasionally associated with neonatal seizures include: • developmental/congenital abnormalities: • neonatal asphyxia/ischemia syndrome • intracranial hemorrhage/trauma/edema

NEONATAL SYNDROMES

INTRODUCTION

PREMATURITY AND DYSMATURITY

Etiology

Clinical signs (Fig. 6.1)

This occurs from several causes including poor, absent intestinal motility (ileus) or uncoordinated excessive intestinal activity or gas accumulation or overfeeding.

This occurs from several causes including poor, absent intestinal motility (ileus) or uncoordinated excessive intestinal activity or gas accumulation or overfeeding.

Respiratory distress syndrome (see p. 275).

Respiratory distress syndrome (see p. 275).

Lung surfactant may be abnormal and result in significant respiratory difficulties (impaired compliance with failure to expand at birth and consequent hypoxia).

Lung surfactant may be abnormal and result in significant respiratory difficulties (impaired compliance with failure to expand at birth and consequent hypoxia).

Slow respiration particularly reflects a poor prognosis and as the central respiratory centres are deprived of oxygen so the control becomes even less effective.

Slow respiration particularly reflects a poor prognosis and as the central respiratory centres are deprived of oxygen so the control becomes even less effective.

Diagnosis

Evidence of hypoventilation: reduced PaO2 (which responds to 100% O2 by rising to normal; withdrawal of the oxygen results is a rapid fall again); increased PaCO2.

Evidence of hypoventilation: reduced PaO2 (which responds to 100% O2 by rising to normal; withdrawal of the oxygen results is a rapid fall again); increased PaCO2.

Acidosis (venous pH 7.25 and tendency to become more acidotic.

Acidosis (venous pH 7.25 and tendency to become more acidotic.

Marginal macrocytic, normochromic anemia (see p. 212).

Marginal macrocytic, normochromic anemia (see p. 212).

Leucopenia due to a profound neutropenia (< 1.0 × 109/L) with lymphocytosis (> 4.0 × 109/L).

Leucopenia due to a profound neutropenia (< 1.0 × 109/L) with lymphocytosis (> 4.0 × 109/L).

Neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio is often narrow or even reversed and a ratio of < 1.0 is accepted as being significantly abnormal; the normal ratio is > 2.0 at 3–4 hours after birth.

Neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio is often narrow or even reversed and a ratio of < 1.0 is accepted as being significantly abnormal; the normal ratio is > 2.0 at 3–4 hours after birth.

Failure of the above parameters to respond to ACTH stimulation test (see below).

Failure of the above parameters to respond to ACTH stimulation test (see below).

Mean cell volume (MCV) is often higher than normal (i.e. > 40 fL).

Mean cell volume (MCV) is often higher than normal (i.e. > 40 fL).

Low blood glucose (values less than 2.5 mmol/L at 2 hours and a decreasing trend are significant findings).

Low blood glucose (values less than 2.5 mmol/L at 2 hours and a decreasing trend are significant findings).

Possible renal/hepatic impairment.

Possible renal/hepatic impairment.

Low colostral absorption with a high tendency to infection. The reasons for this could include poor colostral quality in a mare that foals very early (or late), or failure to ingest the colostrum or failure to absorb the immunoglobulins adequately as result of poor intestinal function.

Low colostral absorption with a high tendency to infection. The reasons for this could include poor colostral quality in a mare that foals very early (or late), or failure to ingest the colostrum or failure to absorb the immunoglobulins adequately as result of poor intestinal function.

Blood cortisol is very low for the first 24 hours (at least) (< 30 ng/mL, normally > 100 ng/mL) (cortisol estimations may not be useful in practice because it takes time to send samples and receive results).

Blood cortisol is very low for the first 24 hours (at least) (< 30 ng/mL, normally > 100 ng/mL) (cortisol estimations may not be useful in practice because it takes time to send samples and receive results).

Little or no change in cortisol levels after exogenous ACTH stimulation (normal full term foals will show at least a threefold increase in plasma cortisol levels following ACTH administration).

Little or no change in cortisol levels after exogenous ACTH stimulation (normal full term foals will show at least a threefold increase in plasma cortisol levels following ACTH administration).

Plasma progestagens are usually elevated for the first 24–48 hours in premature and dysmature foals.7

Plasma progestagens are usually elevated for the first 24–48 hours in premature and dysmature foals.7

Glucose tolerance test (0.5 mg/kg glucose i.v.) – a normal full term foal will show a clear response demonstrated by over a threefold increase in plasma insulin 5 minutes after administration. A premature foal may show a slight response with a twofold increase in plasma insulin, 15 minutes after administration.

Glucose tolerance test (0.5 mg/kg glucose i.v.) – a normal full term foal will show a clear response demonstrated by over a threefold increase in plasma insulin 5 minutes after administration. A premature foal may show a slight response with a twofold increase in plasma insulin, 15 minutes after administration.

Treatment

Specific therapy

Prognosis

Parameter

Favorable

Unfavorable

Placenta

Normal, placentitisb

Chronic changes e.g. villous atrophy

Delivery

Normal, spontaneous, unassisted

Induced parturition, dystocia

Mare’s health

Normal

Colic, surgery, endotoxemia, aged

Foal’s neurological status (at 24 h)

Normal

Poor suckle reflex, deteriorating awareness, seizures

Leukocyte count (× 109/L)

5.0 – rising

< 5.0 persistently

Neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio

≥ 2

< 2 persistently

Plasma fibrinogen (g/L) at birth

> 4

1–3

Blood pH

> 7.3

< 7.3 persistently

Plasma cortisol (ng/mL)

> 120

< 30

Response to aqueous ACTH (0.125 mg i.v. or i.m.)

Widening of N:L ratio, threefold increase in plasma cortisol

No/little change in either N:L ratio or plasma cortisol

Prevention

SEIZURES, WEAKNESS AND ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR

Etiology

Diagnosis

SEIZURES

Etiology

portocaval shunt (these are very rare and usually only cause signs when the foal starts taking solid feed)

portocaval shunt (these are very rare and usually only cause signs when the foal starts taking solid feed)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree