5 Neglect

Malnutrition

General

Malnutrition is poor nutrition that has arisen as a consequence of insufficient or poorly balanced food, or because of faulty digestion or utilisation of food.1 Owners and keepers of animals have a responsibility to investigate the causation of any suspected malnutrition problem in animals under their care. Not to do so is neglectful.

Recognition of severe malnutrition is relatively straightforward and veterinary involvement is usually restricted to those cases involving gross neglect (Figs 5.1 & 5.2). Body condition scoring methods are available for different species of domestic animals and are subdivided for different classes of farm animal, e.g. dairy cows and beef suckler cows and heifers. These guides can be invaluable to clinicians as the veterinarian must have a thorough understanding of the variation in body condition that is the ‘accepted norm’ at different times of the year in the various livestock husbandry systems. Similarly, birds of prey that are used for hunting may have ‘flying weights’ that are significantly less than the ideal weight for a resting bird.

Fig. 5.1 Bull mastiff. Neglected and starved to the point of death over a 5-month period.

(By kind permission of the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.)

Malnutrition, infection and the immune system

The interaction between malnutrition, frequent infection and impaired immune function has been the subject of much interest over many years. In human medicine the cyclical nature of this interrelationship, where each element has an effect on the other two, has been accepted for nearly 40 years following publication of the monograph by Scrimshaw et al.2 Keusch3 provided clarity, in 1990, regarding the manner in which these three factors can result in the downward spiral of bodily condition. These findings are equally valid for domestic animals.

In the past it was assumed that malnutrition was the primary cause that resulted in impaired immune function and subsequent frequent or persistent infections. There is persuasive experimental evidence that this sequence of events can occur.4 However, infection (in the form of parasites or microbial infections) may be the initiating cause of the downward spiral in animals being fed a marginal diet. During infections the patient may have a reduced food intake, compounded by increased energy consumption, catabolism of muscle proteins, loss of nitrogen stores, and depletion of glycogen and fat stores. The animal moves from a state of marginal diet into protein-energy malnutrition. Without an improvement in diet, cell-mediated immunity is impaired and infections persist or recur before the immune damage can be repaired. Thus, the body condition of the animal continues to decline. Interventions to prevent the decline are dependent on improving various aspects of the husbandry to lift the animal from its marginal diet and reduce the disease challenge.

Post-mortem findings in malnutrition

Muscle

Atrophy of muscle masses begins in monogastrics after 24 hours of starvation. In calves and lambs this change takes slightly longer, whilst its onset in adult ruminants is delayed for about 3 days. The back and thigh muscles are first affected but the process extends to all muscle groups (Fig. 5.3). Depletion of glycogen deposits in the muscle cells of emaciated animals interferes with the normal process of rigor mortis. Consequently these bodies do not ‘set’.

Stomach and intestines

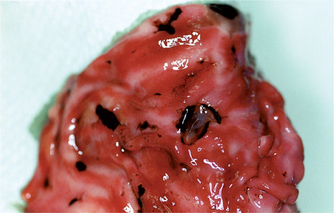

Dogs and cats do not store food in their stomachs for extended periods. In most cases, food passes to the intestines within hours of ingestion. Consequently, in contrast to ruminants, the stomach and small intestines of dogs and cats after several days of starvation may be virtually empty, or may contain only quantities of mucus. Gastric ulceration (Fig. 5.4), caused by reduced blood flow to the lining of the stomach, in malnourished dogs may lead to perforation of the stomach wall. Hungry animals may ingest a variety of indigestible materials (plastic bags, rubber, cloth, wood) and the stomach can become distended with this type of non-food material (Fig. 5.5). Dry or sticky faecal material may be present in the large intestine.

Fig. 5.4 Gastric erosion and ulceration in a severely malnourished and hypothermic greyhound/lurcher puppy.

Natural disease and malnutrition

Post-mortem examination of very thin animals may uncover natural disease or physiological states that could account, at least partially, for the poor bodily condition, e.g. advanced neoplasia (Fig. 5.6), Johne’s disease, heavy parasitism, lactation. The duty of the veterinarian is to make an assessment of the contribution that these processes played in the reduction of body condition and to note whether appropriate veterinary treatment had been sought for the progressive loss of weight. These matters are not always clearcut (Case study 5.1).

Equally important must be the recognition that not all diseases or infections result in poor condition. For example, post-mortem examination of malnourished farm animals will frequently show evidence of limited areas of pneumonia and small numbers of liver flukes or lungworms. Such findings should be recorded and included in the final report, but if it is considered that they lack relevance to the decline in body condition this should be clearly stated.

Neglected injuries: general aspects

Case studies 5.2–5.5 (Figs 5.7–5.12) provide examples of different injuries and interpretations of findings.

Case study 5.2: Neglect of post-calving injuries

During a routine welfare visit by State Veterinary Officers, a filthy, emaciated cow was found tethered. Her perineal area was heavily soiled and necrotic (Fig. 5.7). The farmer reported that she had had ‘a difficult calving’. Checks revealed that the veterinary surgeon had not been contacted regarding this cow. She was euthanased.

A large (150 × 160 mm) necrotic area involved the anus, rectum, vulva and urethra.

The post-calving uterus showed well formed caruncles and widespread endometritis.

Photography of this extensively damaged area was aided by the insertion of coloured markers in the rectum, vagina and urethra before dissection. After the damaged organs had been opened, the coloured markers were replaced and further photographs taken. This process created a series of photographs that clearly demonstrated the location of the various structures and allowed the Court to appreciate the extent of the damage (Fig. 5.8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree