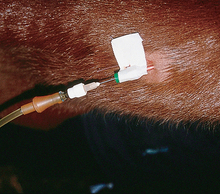

Chapter 9 Many diseases and conditions can be effectively treated on the farm but this will depend on: • the facilities available for nursing of both mare and foal • the number of support staff available and their ability and experience (enthusiasm is seldom in short supply – at least in the early stages of the nursing) • the experience and facilities of the clinician • the condition of the foal and the mare and their tolerance of transportation (e.g. some mares may not tolerate transport and so might jeopardize the foal and its handlers) • the specific needs of the patient (e.g. splinting of a fractured leg, control of seizures, correction of hydration and electrolyte status, etc.) • the distance to the center and the time the journey is likely to take • the type of vehicle available for the transportation (sometimes the foal will be taken alone but usually both dam and foal will travel together and may need to be physically separated without being out of sight). A handler may have to travel with the foal and so will need to be safe also. 1. An early decision to refer is clearly better than undue delay. There is little rationale in sending a dying foal, which has little or no hope of surviving the journey, let alone the rigors of an intensive care regimen. The mare and the foal should be considered together and individually. Consider the whole foal and not just the condition that is of most concern at this time; for example, the foal may have ‘bent’ legs or a septic joint, etc., which might influence the prognosis markedly. 2. Referral should be considered seriously. A journey may make the condition worse. It is wise to seek advice from the referral hospital early if there are doubts about the necessity to transport the foal. Keep the referral center aware of the progress or otherwise. This will also give the center useful information before admission. 3. The likely cost of the procedure must be discussed with the owner or stud manager. Foal intensive care is very expensive* and the implications (win or lose) need to be considered before starting out. 4. If the foal is insured the company should be informed; this is often forgotten in the heat of the moment and failure to comply with policy procedures may create difficulties later on. 5. Give the owner a proper assessment of the likely prognosis. It is unwise to promise that the specialist facility will save the foal and produce an ideal outcome. 6. Consider whether sufficient care can be given with the facilities you have available to yourself and on the farm: a. Are the correct drugs, fluids and catheters available? b. Is the correct equipment available? Laboratory support may be essential to the survival of the foal in some cases but in others minimal supportive equipment may be needed. c. Is environment conducive to the maintenance of body temperature and hygiene? d. Is a suitable stomach tube or foal feeding tube available? e. Can oxygen be administered easily and safely over the full 24-hour day? g. Assuming that all the equipment for the particular foal is present does the clinician have experience in their use/administration? h. Is there suitable, experienced help available to maintain the effort after the clinician leaves the premises? 7. The nearest referral center with known expertise and the facilities to cope should be selected. There is no point in sending the foal to another similarly equipped or experienced practice just to shift responsibility for the foal to someone else. Remember, there are plenty of places with the facilities but fewer perhaps with the expertise. It is useful to identify suitable hospitals before the stud season starts and have a working relationship with them. 8. Phone and discuss the case early (preparation is maximized and guidance can be given which might save the foal’s life or prevent an unnecessary journey). In addition, many referral centers have a particular preference for various treatment regimens and antibiotics. 9. A written record of all clinical findings and any procedures (including the timing and doses of any drugs given) should be sent with the foal. You should sign the letter and it should include contact numbers and addresses. 10. All specimens taken (e.g. peritoneal fluid, blood or joint fluid) should be packed accordingly and sent with the foal. 11. As soon as laboratory results become available these should be sent by fax or email to the referral center. 12. The placenta should be sent if available (packed on ice in a clean, sealed plastic bag). 13. If the mare is not accompanying the foal, some milk/colostrum should be obtained and sent with the foal. • Avoid draughts in the transporter – but also avoid a steamy moist atmosphere by ensuring adequate ventilation. • Equine ambulances are excellent but may not be equipped to transport a mare and foal. • Do not put a sick foal in the boot of a saloon car. Stop at regular intervals unless separate staff are looking after the animals. Some foals will not nurse when moving so it may be necessary to stop to allow feeding. If the foal is in pain and thrashing or convulsing, give suitable medication to control pain and seizures (see p. 60). Seizure control is usually best using diazepam at 5–20 mg to effect in 5 mg increments (see p. 68).2,3 Handlers may be instructed to administer repeat doses during travel via an intravenous catheter. Always check the blood glucose of any convulsing neonatal foal prior to and during transportation. Foals inclined to convulsions or uncoordinated movement need to be fully bandaged with protective padding on limbs and head to prevent injuries. Protective headgear is available commercially (Foal Hoods, High Horse Therapeutic Products, PO Box 11212, Reno, Nevada 89511) (Fig. 9.1). Alternatively a properly fitting foal slip should be used with suitable padding. In an emergency, sleeping bags, sweaters (with the foal’s front legs through the arms and head through the neck) (see Fig. 8.7 on p. 414) are good, simple measures. Hot-water bottles and electrically heated pads can be valuable but they can cause serious skin burns especially in compromised recumbent foals. Do not put the foal on to hot surfaces – application of direct heat can harm the circulation and cause skin damage/thermal necrosis. It is sometimes possible to have the foal in the heated cab and still within sight of the mare. If the foal is traveling ‘on fluids’ these should be warm – see below. Energy, fluids and electrolytes are the earliest and most significant requirements. Maintenance of normal blood glucose is particularly important for recumbent or weak foals. Blood glucose should be checked before departure. If blood glucose is less than 2.5mmol/L and the journey is likely to be longer than 1–2 hours it is wise to place an intravenous catheter and administer warm 5% glucose solution at 4mL/kg body weight/h. It is probably unwise to administer a large bolus of glucose intravenously at the start of the journey as this might easily induce a ‘rebound’ hypoglycemia. It is possible to keep fluids warm using commercially available warming devices (Direct Medical Supplies Ltd., Forest Lodge, Hampshire, UK). Fluid therapy may need to be maintained for the duration of the journey and so suitable arrangements have to be made using a ‘SUSI’ flexible, extendible intravenous administration set (Direct Medical Supplies Ltd, Forest Lodge, Hampshire, UK or Vet Drug/Genus, Dunnington, UK). If the foal has any respiratory compromise4 ideally it should not be left in lateral recumbency, as sternal recumbency is very helpful to normal lung function. Oxygen should be administered if: • the respiratory rate is less than 30 per minute or greater than 80 per minute • mucous membranes are pale or cyanotic Oxygen cylinders and possibly an indwelling nasal tube (Cook, Monroe House, Letchworth, Herts, UK) with continuous oxygen can be used. A nasopharyngeal tube is easy to insert and is well tolerated by foals (see p. 385). A direct oxygen line into the trachea inserted percutaneously is also available. Oxygen can be administered directly via a normal cylinder with a pressure-limiting valve. A demand valve can also be used. Unless the foal is already known to be infected, it is probably wise to delay the administration of antibiotics. However, if there is any suspicion at all of sepsis a suitable broad spectrum antibiotic may be administered by catheter (Fig. 9.2). It may be useful to discuss the antibiotic selection with the referral center. Any drugs given must be recorded. • Most mares tolerate transportation in sight of the foal very well. • Leg bandages should be applied to the mare as is the norm for traveling. • A hay net may be a useful distraction to her. • Sedation may be needed if she is disturbed by the procedure in any way. The last thing that is needed is a mare that becomes uncontrollable during the journey. (A familiar handler is a very useful asset!) • Observe her udder. If the foal does not feed and the journey time is long she may need to be milked out. • In order to obtain its minimum requirement a healthy foal must drink approximately 10–15% of its body weight in the first few days and then up to 25% after that. Normally the newborn foal would achieve this by feeding up to seven times per hour ingesting about 80 ml per feed. Clearly this is impossible to mimic under artificial conditions. A foal fostering kit is shown in Figure 9.3.

MISCELLANEOUS

REFERRAL OF FOALS TO A SPECIALIST CENTER

CONSIDERATIONS PRIOR TO REFERRAL OF A SICK FOAL TO A SPECIALIST UNIT1

TRANSPORTATION OF THE SICK OR INJURED FOAL

MODE OF TRANSPORT

Some of the most significant aspects during transport1,2

Safety for foal, mare and handlers (i.e. restraint and protection from self-inflicted or other trauma)

Prevention of hypothermia

Maintenance of blood glucose and prevention of nutritional depletion

Lung function

Antibiotic

The mare

MANAGEMENT OF THE ORPHAN FOAL

HAND REARING THE ORPHAN FOAL

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

MISCELLANEOUS